Inside the Vision of Nancy Burson: The Artist Who Reveals the Unseen

This piece emerges from a recent, wide-ranging conversation with Nancy Burson — the latest chapter in a dialogue Kate Vass and the artist have been fortunate to sustain over the past several years. Over the course of three hours, Nancy walked us through decades of pioneering work at the intersection of art, science, and technology. What follows is a reflection on that exchange — an attempt to trace the arc of a visionary whose contributions not only shaped the trajectory of digital imaging, but continue to influence how we understand identity, perception, and the role of technology in contemporary art.

Nancy Burson, A Projection of Love Through the Stars, 2024 © Nancy Burson

Nancy Burson is a pioneering American artist and inventor whose work has shaped both the history of digital imaging and the future of human identity. In the early 1980s, she co-created the first patented facial morphing software, a technology later adopted by the FBI and used to age photographs of missing children, leading to real-world rescues. Her work merged art and science decades before it became common practice, anticipating today’s conversations around AI and biometrics. She has served as adjunct photography faculty at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts and as a visiting professor at Harvard.

Alongside her technological breakthroughs, Burson’s art has been exhibited worldwide, often challenging traditional boundaries between image-making and metaphysical exploration. Her composite portraits of political leaders, idealized beauty, and altered identities have forced viewers to confront who we are and what is projected onto us.

For over 30 years, she has also been documenting unseen phenomena and metaphysical events that she believes are part of our deeper cosmological structure. These experiences, often dismissed or misunderstood, form a parallel body of artwork that fuses physics, consciousness, and what she calls “our lineage of light.”

Nancy Burson: Milestones in a Boundary-Breaking Career

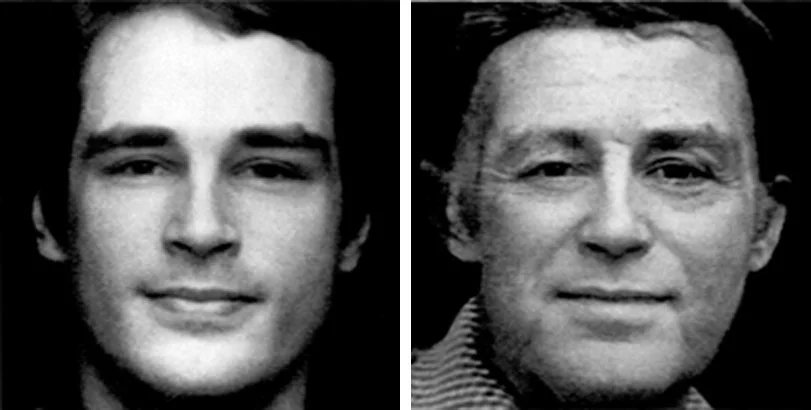

Burson’s breakthrough arrived in 1981, when she was granted the patent “Method and Apparatus for Producing an Image of a Person’s Face at a Different Age.” Two years later, she began working with the FBI on the Etan Patz case, and by 1987, the Bureau had fully licensed her software. Her pioneering work in facial morphing technologies and digital manipulation enabled law enforcement officials to locate missing children and adults, and the methodology of these technologies are still used to assist enforcement officials in locating missing persons. The Age Machine itself debuted publicly in a 1992 New Museum window installation, allowing passers-by to watch the action of participants aging by computer just inside the museum.

Nancy Burson, Method and Apparatus For Producing an Image of A Person’s Face at a Different Age, 1978 © Nancy Burson

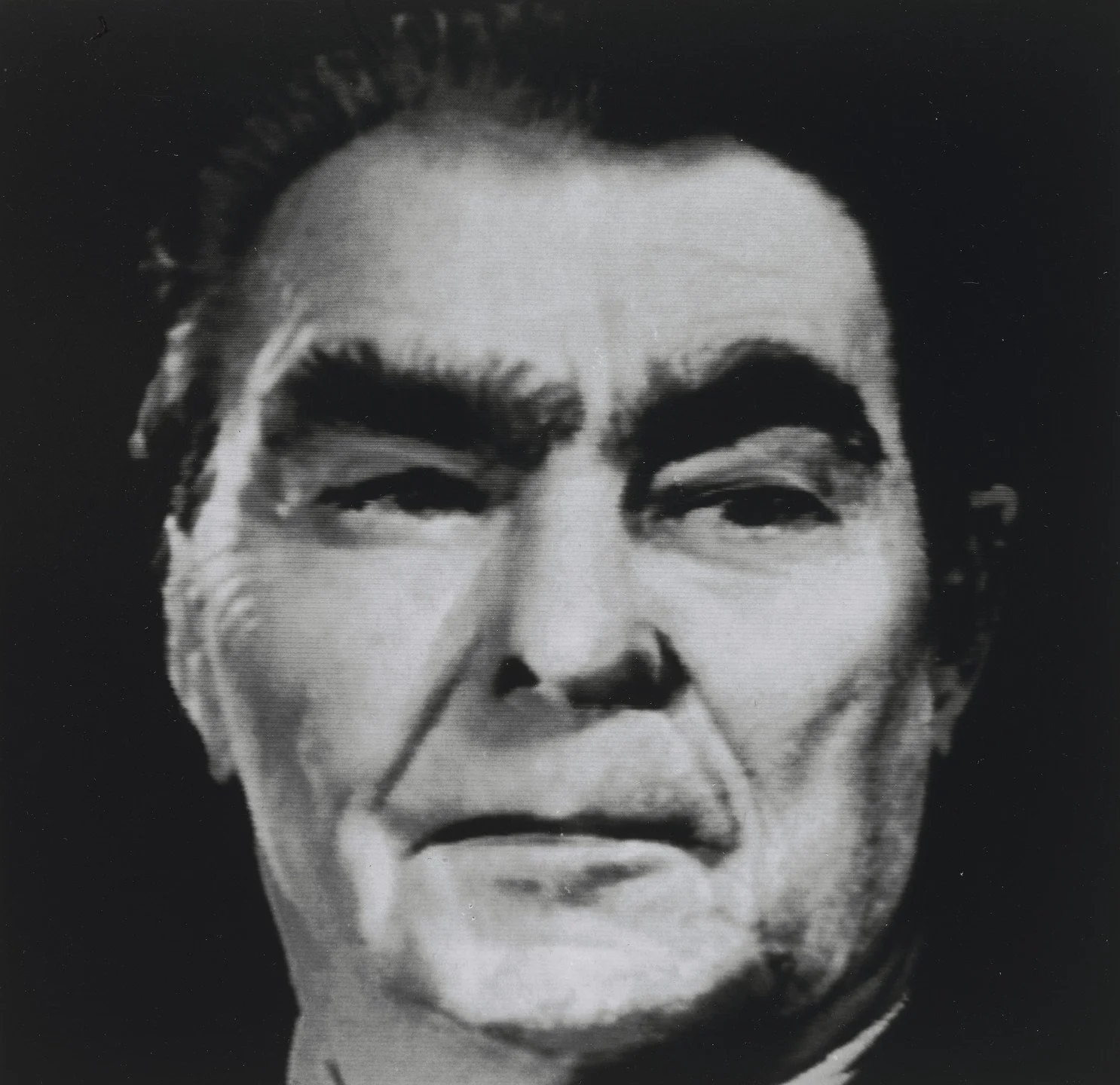

Throughout the early 1980s Burson used her morphing code to create politically charged composites: Warhead I (1982) blended the faces of Reagan, Brezhnev, Thatcher, Mitterrand, and Deng according to each leader’s share of nuclear warheads. It resides in the Met’s permanent collection and was featured in its 2012 exhibition,“After Photoshop.”

In Big Brother (1983), she fused Hitler, Stalin, Khomeini, Mao, and Mussolini into one ominous visage, a work still exhibited at Art Basel and media-arts archives worldwide. The Whitney later acquired and showed Mankind (1983-5), a tri-racial composite weighted by global population statistics.

Burson’s interactive Human Race Machine, commissioned for London’s Millennium Dome in 2000, let viewers see themselves as six different racial categories and toured universities as a diversity-education tool for over a decade.

Her face-morphing became cultural shorthand in 2018 when TIME magazine commissioned Burson to merge Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin for its “Summit Crisis” cover, an image that ricocheted across global newsfeeds and cemented her status as a pioneer of political photomontage. The same morphing techniques had already earned her a spot in TIME’s book of “100 Photographs: The Most Influential Images of All Time.” Her work has also been featured in The New York Times Magazine, The New York Times. The Houston Chronicle, and Scientific American Magazine to name a few. There are four monographs of her work and reproductions of it appear in hundreds of art catalogs. It is also widely featured in textbooks on the history of photography published in all languages. Her work has been featured in all forms of media including segments on Oprah, Good Morning America, CBS Evening News, CNN, National Public Radio, PBS, and Fuji TV News, as well as countless local TV segments in the USA, Canada, and Europe.

Nancy Burson, Trump/Putin, 2018 © Nancy Burson

Burson’s work now resides in MoMA, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney, the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Centre Pompidou, LACMA, the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, San Francisco MOMA, the Getty Museum, and the Smithsonian Museum as well as galleries internationally. Her 2002 retrospective “Seeing and Believing” (Grey Art Museum) was nominated for Best Solo Museum Show of the Year by the International Association of Art Critics. She has collaborated with Creative Time, the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, and Deutsche Bank in completing several important public art projects in NYC. These projects include the poster/postcard project “Focus on Peace”, commissioned for the first anniversary of 9/11. Since 2013, Burson’s public artworks were displayed as works projected in light in both the Berlin Festival of Light and the New York Festival of Light.

Between 2011 and now, Burson periodically shifts from code to handwriting in the Love’s Letters series, repeatedly inscribing LOVE and iLoveYou across large photographic prints with both hands, a method she describes as “overdrawn and painted two-handed for brain balancing.” The dense overlays dissolve into shimmering color fields, linking written affection to the “love frequencies” she explores in her endless writing of Love’s Letter’s paintings. A couple of these handwritten works appear in her video piece “A Projection of Love Through the Stars”, which was recently included in “Body Anxiety in the Age of AI” on objkt.com.

Recently, film director Anthony Werhun captured her trajectory in the 2023 short documentary It’s Not Up To Us, which traces Burson’s journey. The film, produced by SRW Films, was screened at fifteen festivals and took four Best Documentary Short awards, including one at the Philip K. Dick European Science Fiction Film Festival.

Nancy Burson, Warhead I (Ronald Reagan, Leonid Brezhnev, Margaret Thatcher, François Mitterand, and Deng Xiaoping), 1982 © Nancy Burson

Nancy Burson, Big Brother (Hitler, Stalin, Khomeini, Mao and Mussolini), 1983 © Nancy Burson

In addition to this, Burson will also appear in a new film by director Ron James titled Accidental Truths: NEXT, which premieres in August. The documentary, a follow-up to James’s first film, Accidental Truths, includes a new interview with Burson and explores the mysteries of UFOs, now referred to as UAPs.

Foundations of a Visionary

In the late 1960s, pop culture saturated every New York newsstand, and Time magazine was still a weekly lodestar of visual journalism. One afternoon, teenage Nancy Burson paused over a short feature that imagined the four Beatles decades in the future. “It was something that I saw about the Beatles aged, but no one’s ever been able to find that article. Those images became the kernel of an idea that changed everything.”

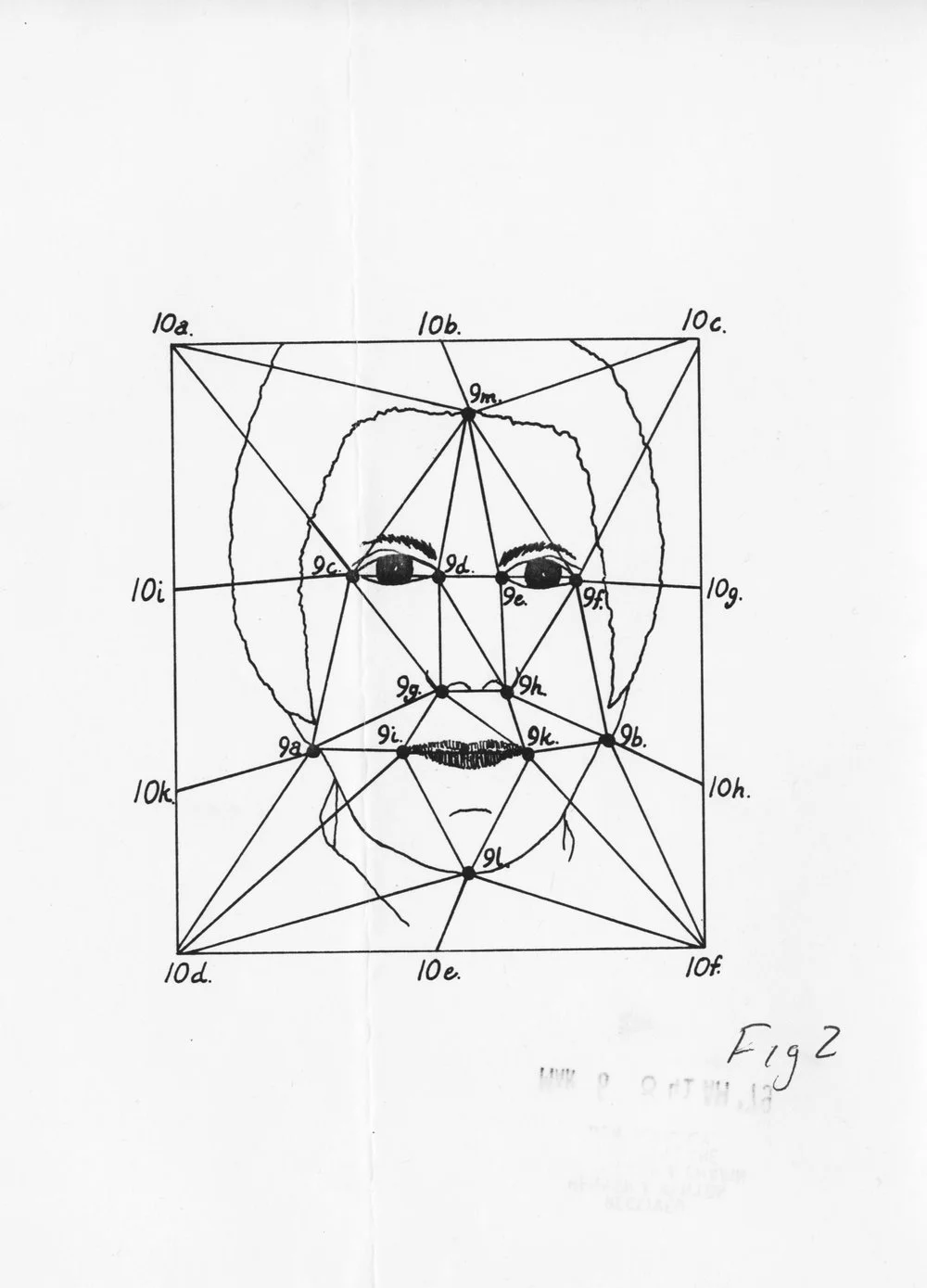

For most readers, the sketch was a curiosity; for Burson, it was proof that a portrait could act like a time machine. That thought immediately collided with another insight she’d been observing: “The interesting thing about faces is that no one ever agrees. Everyone sees what they see from their point of view, from the lenses of their own eyes.” If perception was that subjective, any tool that altered a face would need to be participatory, inviting each viewer to test their private lens against the machine’s output. Burson's early insights foreshadowed how her later work challenged photographic truth by questioning the reliability and objectivity of images.

Nancy Burson, Morphing Grid, 1979 © Nancy Burson

To build such a device, she went to Experiments in Art & Technology (EAT), telling the engineers she met that she wanted “to create a participatory work of art that would somehow be an interactive video installation.” Nancy was partnered with an early computer graphics expert and was shown a pen attached to a tablet. Knowing Nancy was unimpressed with the state of technology he told Nancy she would have to wait for the technology to catch up to her idea. Between 1969 and 1976, Nancy kept in touch with the graphics consultant who in 1976 urged her to reach out to Nickolas Negroponte, head of what was then called the Architecture Machine Group at MIT. That department is now infamously known as MIT’s Media Lab. Between those years Burson was there for many all-nighters, mostly on weekends, that were spent with various programmers as well as Thomas Schneider, the co-inventor on her patent. Ater the engineers made a successful video of three faces aging by computer, Nancy left MIT with the consent of Negroponte and her patent issued in 1981.

The proposal to create an Aging Machine reached Marcia Tucker, founder of the New Museum, in 1992. Burson has a vivid recollection of Tucker’s acceptance of the project. “Do you really think that people are going to want to see themselves older in the windows on Broadway?” Tucker didn’t blink: “Yes. Yes, I absolutely do.” That exchange validated Burson’s hunch that curiosity about our future faces is universal, and it sketched the blueprint for every aging kiosk, composite portrait, and facial-morphing software she would pioneer. Long before deepfakes or Instagram filters, Burson had already reframed the human face as data in motion, inviting the world to watch itself change.

Blood and Microscopy

To understand how she had the eyes to see that future, you have to understand where she came from. Burson grew up inside a world of observation. Her mother worked as a lab technician, and young Nancy, curious, sharp, and intuitive, was brought along into that quiet theater of science.

“The fake experiments I did with real blood was when I was a little girl in labs where my mother had worked,” she recalls. “Since my mom was a lab technician, I was brought up more in science than religion”. That early exposure to data, material, and precision shaped her way of seeing.

When she started making art, she wanted the truth of how identity changes, how perception mutates, and how technology could make the invisible, like aging, bias, or ancestry, impossible to ignore.

Nancy Burson, The Age Machine, 1992 © Nancy Burson

Nancy Burson, Human Race Machine, 2000 © Nancy Burson

The Limits of Perception

“According to some MIT research years ago, we make up our minds about someone within two to four seconds based on their face.” When her son was a baby, she saw that happen every day. Strolling the neighborhood shops, she would take her son out, and within one block would hear, ‘Oh, your child looks exactly like you.’ And then by the end of the block someone else would say, ‘Oh, he looks exactly like your husband.’”

Burson understood that what people think they “see” is often just a reflection of what they believe, want, or project. Her morphing software that producing composites and age-progressed images were philosophical provocations. What constitutes a male or female face and what would happen if you could combine six of each together? Would it be more masculine or feminine? Or what happens if you combine the world’s leaders together and weighted them to the number of nuclear arms their country possesses? Who gets seen? And who gets erased?

Burson’s early career reads like a blueprint drawn by something larger than logic. The right images, the right mentors, the right visions, all arriving in uncanny order. “It’s a destiny thing,” she says with soft certainty. “Everything is predetermined”. But destiny isn’t enough. It needs a mind willing to see it, and hands willing to build it. In my opinion, Nancy Burson has both.

The Face as Data

Recently, one of Burson’s most powerful images of real people was selected from a private collection and donated to MoMA’s permanent collection. It’s a 20 X 24” Polaroid of a man who had lost part of his face to cancer. “All those people that I photographed at the same time were patients of a doctor friend of mine at Sloan Kettering,” she said. “He was the head of dentistry, and he was making prosthetic devices for his patients who had undergone extensive surgeries from facial cancers.”

“Now MoMA has their own signature Polaroid camera they’ve marketed for their museum stores,” she added. “And they mentioned four or five photographers: Andy Warhol, Ansel Adams, Robert Frank, and me. And I was like, Wow! I’m suddenly somewhere I never expected to be!” Even in that moment of arrival, Burson sounded surprised, grateful, and simultaneously aware of how strange her path has been.

Nancy Burson, Untitled (Mr. Buggs), 1994 © Nancy Burson

The Turn Toward the Invisible

From the mid 90’s, Nancy’s own ill health propelled her to seek alternative approaches to western medicine. When she began to meditate and study metaphysics, she found she was somehow able to photograph the energy around herself and others. With her newfound skills, recovering health, and perception of destiny suddenly changed, she was immediately drawn to the documentation of her own personal experience.

When Nancy began to see tiny snippets of brilliant lights twinkling in white, blue, red, and purple, no one she asked could explain them. She considers herself a science-based person, so no angelic explanation made sense. Nancy left behind the notions of spirituality expressed by her teachers of metaphysics and fully embraced her observations as science.

Through the decades, the luminous flashes of light she could see expanded and eventually began to communicate as well. She says, “I don’t see dead people, or angels, or aliens. I see physics. I see what appears around me as grids of golden threads. I see the “cosmic web” in the darkness and the light of day. I see its emergent patterns sitting quietly on the land as it appears to cover the Earth in a curved weblike structure. I see luminous flashes of light and tiny interlocking spirals of silver light.”

In 2008, what she describes as MOUOs, or Materials of Unknown Origin, began to appear out of nowhere. They remain a mysterious story in themselves, appearing periodically since then and again just a few weeks before this interview. “They either land in my drawers, or they land in the homes of people who are close to me—whether they’re assistants in photographing them, or my closest friends,” she says.

They’re small, “like small peas, and when analyzed they defy simple classification. The NIH, NASA, and other government-linked researchers examined them, but the results were most often withheld. In one case, Burson was told only that the material “emitted an unknown light source” and was made of “an unknown amino acid”. It was, for Burson, a turning point. The rupture had opened, and the science was no longer just something she brought into art. It was starting to come to her.

2009 marked an even bigger rupture when her body suddenly began to produce small crystals which since then have been collectible daily in her socks. Nancy has diligently documented them like scientific evidence because her guidance has consistently told her they’re valuable for physics.

Over the years, Burson has had the crystals analyzed by multiple laboratories and each analysis is quite different, as it seems they are both organic and inorganic. Recently at Yale, a doctoral student took an interest and had them tested across several departments. “The scientists at Yale were able to image the network of stronger material covering them. That stronger material is a kind of glaze that’s covering the crystals. It’s also covering my paintings, my drawings, my clothing, my plates, and even my food. Another recent test revealed there are large amounts of silicon-based substances not found in human bodies coating them.”

Burson uses her vision to recreate the emergent behavior patterns she sees in the air on canvas. That can be created by making 2 marks I represent as sets of eyes. I make two up and two down, repeated endlessly. “When you use that pattern… you basically have the frequency of quantum entanglement which is simply one particle communicating with another, no matter how far they are apart.” The paintings are black and white but using a mobile phone in video mode and the palette shifts and viewers record different colors.

Process is as important as spectrum. Every mark is made ambidextrously: “Anything that I can do two-handed makes me happy because it balances my brain.” The left–right motion, she says, synchronizes hemispheres, turning painting and drawing into a live neuro-feedback loop. The finished surface is a resonant field; a portal tuned to interactive examples of quantum physics.

Nancy Burson, Quantum Entanglement #2, 2021 © Nancy Burson

Orbs of Light

Nancy shares with me that she sees orbs, or balls of light around herself and others. “There are balls of light around everybody,” she says matter-of-factly. “I see them as plasma physics”. Others might call them ghosts, angels, or UFOs. Burson calls them her lineage. “Each of us have at least two balls of light with us,” she explains. “One that’s maternal and one that’s paternal. They are our lineage of light that act as our guidance”.

In the dark with Mary and the Quantum Entangled Balls

In 2005, Burson bought a small glow-in-the-dark Virgin Mary and began staging performances in cities across the US, England, and even at the UN. Now days, Mary is accompanied by two glow-in-the-dark balls that represent quantum entanglement. Audiences were invited to watch without ambient light as cameras routinely capture floating orbs around the statues.

Nancy Burson, Mary and the Quantum Entangled Balls © Nancy Burson

Nancy says, “I use glow-in-the-dark statues of two interlocking spheres and Mother Mary as tools for audiences to see and experience the movement of the energies in the darkness around them. Many participants see things previously outside their realm of perception. For instance, most attendees see the statues appear to move. Others see some aspect of energy in the form of tiny luminous multicolored lights, and/or patches or spheres of light. There are particles of energy moving around us all the time. It’s an interactive experience led by me and in collaboration with the physics that surround all of us!”

Nancy’s Projection of Love Through the Stars is a recent video work that will be shown in Our Time Is Also the Future: New Corporeality. The video simulates a fly-through of deep space, composited with Burson’s hand-drawings created by the repeated writing of the word Love. The video was created using a combination of generative software and AI, and incorporates simulated fast radio bursts (FRBs) rendered as flashes of starlight. The work serves as a positive message—that love, as the highest form of consciousness, can transmute negativity and offer a unifying presence across the heavens and Earth.

Lineage & Destiny

Burson’s knowledge of her own lineage came as an answer to all she continues to experience today. Her DNA analysis and haplogroup discoveries confirm a specific set of genes brought from Moses through his brother Aaron. About 1500 years later that same lineage also fell to the family of Jesus. Andrew was a cousin of Jesus and now the only saint whose body still emits a form of manna even today. Burson insists the crystals are her form of manna, here to somehow impact modern physics. If prophetic bloodlines and quantum spheres converge inside one artist, then the boundaries between scripture, physics, and studio are more porous than critics dare admit.

Nancy Burson has always known her work would test the patience of institutions that once celebrated her software patents and museum retrospectives. “I’m certainly concerned about what’s going to happen to my reputation,” she confided. Yet Burson’s trajectory echoes other visionaries whose discoveries out-raced public comprehension. Hilma af Klint obediently sealed away her own channelled diagrams until fifty years after her death, convinced the future would read them more clearly than her peers.

Cancer patient Henrietta Lack’s cells, dubbed HeLa cells, remain the source of the first immortal human cell line used for the past seventy years for worldwide research in polio, cancer, AIDS, and even Covid. They remain the world’s gift to science resulting from a woman’s unfortunate struggle with her health. However, Henrietta Lacks didn’t live to know what her cells had accomplished. Could the odd composition of Nancy’s crystals provide the appropriate metamaterials for physicists to move quantum computing forward? And would she live to see it?

Post af Klint, Burson now feels the joy that others are experiencing when viewing her Quantum Entanglement paintings. She says, “Use your cell phone to record the painting changing colors, as the painting provides a living example of the quantum world meant to be experiential”.

Unlike af Klint, Burson refuses to lock her evidence in storage. The bluntness, she knows, may cost her columns of press, but so did af Klint’s séance notebooks. What binds the two women is the patience to trust a timeline bigger than any one lifetime, as was also indicated by the technological advancements that emerged after the creation of her Age Machine. Notably, the methodology of the growth of the facial structure is still being used by the FBI to locate missing persons, demonstrating the sustained influence and long-term impact of her work.

That patience crystallises in Burson’s closing mantra, delivered without drama or complaint: “If the door opens,” she says, “then it’s meant to be open. It’s a destiny thing.” Reputation, credibility, and misunderstanding may hover at the threshold, but she will keep pushing evidence—orb photographs, ambidextrous canvases that mimic particle physics, mitochondrial lineages—through every crack of opportunity. Whether the art world steps through now or in a century is secondary. The door, after all, was scripted to open; her task has always been to hold it wide.