★Why We Look Together: CryptoPunks and the Psychology of Collective Attention

Why do thousands of people care about the same 24×24 pixel faces - and what does that reveal about how culture forms?

CryptoPunks sit at the center of our curatorial history not because of what they later became, but because of what they first demanded: a recalibration of attention.

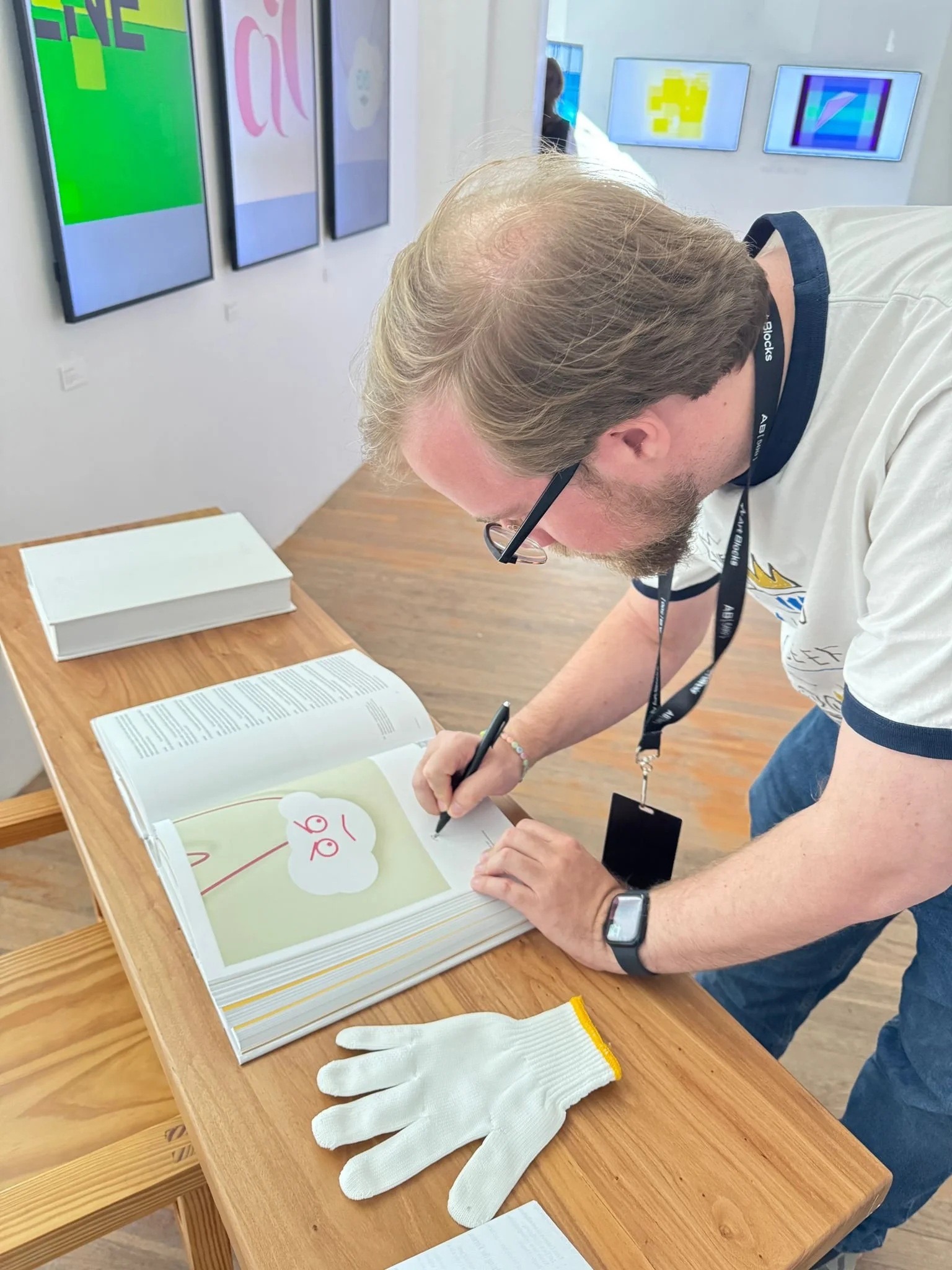

In 2018, when we presented CryptoPunks as artworks in Perfect & Priceless, the gesture was neither symbolic nor retrospective. It marked the first time these on-chain objects were framed explicitly as art within a gallery context in Zurich - physically printed, signed, and publicly acknowledged by Matt Hall and John Watkinson not as developers, but as artists.

At that moment, nothing about CryptoPunks felt inevitable. They appeared fragile, even awkward: tiny pixelated faces, rigidly constrained, carrying a conviction that was difficult to articulate yet impossible to dismiss. Their presence resisted spectacle. Their scale resisted authority. To show them as artworks was less an act of certainty than of intuition - a sense that something structural was unfolding, even if the vocabulary to describe it had not yet stabilized.

The skepticism they provoked was not only aesthetic, but perceptual. Viewers did not yet know how to look at them - or what kind of attention they required. And yet, with time, these same images became among the most recognizable cultural artifacts of the 21st century: circulating simultaneously as artworks, avatars, status symbols, financial instruments, and historical reference points.

This essay does not approach CryptoPunks as isolated images or market phenomena. It treats them as an unusually legible case study of how culture forms under networked conditions - how attention synchronizes, how meaning accumulates, and how network power emerges over time.

Installation view of CryptoPunks: 24 unique signed prints with sealed envelopes granting access to the digital punks, Perfect & Priceless, Kate Vass Galerie, Zurich, 2018. Image Credit: Kate Vass Galerie

From Objects to Signals: How Networks Learn What to See

Under networked conditions, culture no longer forms through singular authorship or institutional approval. It forms through coordination.

Long before something becomes meaningful, it becomes visible. And long before it becomes visible everywhere, it becomes visible together. Digital culture is not persuaded into existence; it emerges through the slow alignment of attention. Shared looking precedes shared understanding. Repetition precedes belief.

This dynamic predates blockchains. Early internet culture - forums, image boards, chat rooms - already showed how meaning could emerge without permission. Memes, avatars, and in-jokes succeeded not because they were authoritative, but because people kept returning to them together. What digital systems changed was not the mechanism, but its speed, persistence, and visibility. Attention became public, measurable, and cumulative.

Long before something becomes meaningful, it becomes visible together. Image credit: Punk DAO

CryptoPunks emerged inside this logic.

Their early circulation across Twitter, crypto forums, and early Discords did not immediately produce agreement about what they were or why they mattered. What it produced was synchronized looking. Before people agreed on meaning, they agreed - often unconsciously - that these images were worth looking at together.

Collectors compared traits, debated rarity, and slowly developed a shared vocabulary. Through repetition and proximity, a grammar formed. Familiarity bred legitimacy. Recognition invited participation. This marks a crucial inversion: value does not precede attention; attention creates the conditions for value to emerge.

CryptoPunks did not go viral so quickly as they may seem. For years, they occupied a liminal state - recognized by some, ignored by many. In their interview in Collecting Art Onchain, Matt Hall and John Watkinson recall that “it was just a small group of people who were interested at the time, so it was still a pretty small scene.” (Proof of Punk: When Code Became Culture, in Collecting Art Onchain, 2025. p. 89.) But networks operate with thresholds. Once enough people realize that others are also looking, attention becomes self-reinforcing. Visibility no longer depends on novelty, but on mutual acknowledgment.

At that point, CryptoPunks ceased to function merely as images. They became social signals. To hold one, display one, or reference one was to signal participation in a shared history of looking. Their significance lies less in being early NFTs than in documenting how digital culture now learns what to see.

CryptoPunks displayed on a digital billboard in Times Square, 2021. Image credit: Alexi Rosenfeld/Getty Images

The Return of the Face: Identity After Anonymity

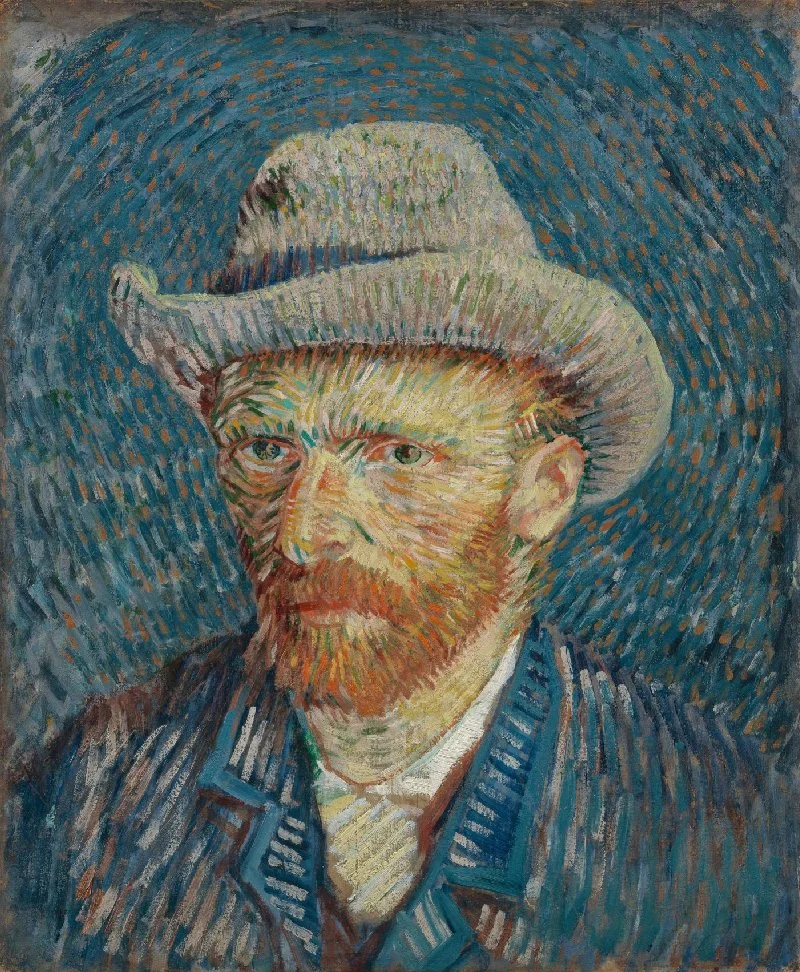

The rise of CryptoPunks exposes a central paradox of the digital age. Early internet culture - shaped by cyberpunk imaginaries and libertarian ideals - promised post-identity fluidity: anonymity, usernames, disembodiment, and escape from fixed social markers. Yet as decentralized systems matured, identity collapsed back into faces.

This return is not accidental. The face is humanity’s oldest social interface. Across cultures, faces anchor trust, recognition, and status. Masks, portraits, icons, and effigies have long mediated between the individual and the collective. Digital psychology consistently shows that faces trigger rapid affective responses, enabling attribution, memory, and social bonding even in abstract environments.

CryptoPunks are paradoxical objects: anonymous yet deeply personal; generic yet singular; mass-produced yet intensely identified with. They function simultaneously as masks and portraits. As avatars, they protect privacy. As faces, they enable recognition. In trustless systems - where legal identity is absent and interaction is mediated by wallets rather than names - the face re-emerges as a stabilizing symbolic anchor.

Web3, in some way, reconfigured identity. Reputation replaced biography. The avatar became a reputation container - a visual proxy through which trust, credibility, and continuity could be negotiated without revealing the person behind it. Matt Hall and John Watkinson explicitly hoped that collectors would adopt Punks as personal identities. The minimalist, video-game-inspired aesthetic enabled this shift. As they explained, “the minimalist, video game art-inspired portrait aesthetic allowed owners to proudly display their CryptoPunks as their profile pictures on social media.” (Proof of Punk: When Code Became Culture, in Collecting Art Onchain, 2025. p. 76.)

The Punk moved from image to interface.

The avatar became a reputation container, a visual proxy for trust, credibility, and continuity without revealing the person behind it. Image credit: curated.xyz

Even in systems designed to decentralize authority, humans continue to organize belonging around faces.

Seen this way, CryptoPunks belong to a much longer lineage. Roman busts marked citizenship. Funerary portraits bound identity to memory. Coins circulated authority through repetition. Heraldry compressed belonging into readable systems. In each case, the face functioned as an interface - a way to be recognized and situated within a collective.

CryptoPunks are not expressive portraits in the art-historical sense. They are recognition devices. Their power lies not in depiction, but in reliable legibility within a shared network.

Intention, Restraint, and the Metaphysics of Release

CryptoPunks emerged from an experiment with remarkably little strategic foresight: no presale, no roadmap, no royalties, no institutional backing. And yet, it produced coherence rather than collapse.

The free-to-claim mechanism was central. While technical barriers still existed, the absence of presales and whitelists delayed speculation and foregrounded participation. Ownership was motivated by curiosity rather than capital. There was no demand to perform belief, no narrative to optimize returns. The system was released - and then left alone. Looking back, Hall and Watkinson note that introducing barriers such as paid mints or royalties could have altered the project fundamentally: “making the CryptoPunks not free to claim, or attempting to charge a royalty on sales may have changed the entire trajectory of the project, or possibly even caused it to fail to take off at all.” (Proof of Punk: When Code Became Culture, in Collecting Art Onchain, 2025. p. 76.)

By refusing to over-determine outcomes, the creators allowed the network to do its own work. Trust did not emerge from authority or persuasion, but from transparent code and shared uncertainty. Participation itself became the medium of meaning.

There is a metaphysical dimension here that is difficult to ignore. In complex systems, intention reveals itself retroactively, through outcome rather than declaration. When incentives are misaligned, networks fracture. When extraction is embedded, cultures thin out. When attention is coerced, belief collapses.

The sustained coherence of the CryptoPunks network suggests that something in the initial conditions was unusually clean.

At scale, meaning no longer resided in any single Punk. It emerged from the relational field among them. Value became social rather than intrinsic. As Larva Labs later reflected, even the edition size became part of this social calibration: “the project grew into the 10,000 number and it became a kind of ‘Goldilocks’ amount; rare enough to still be precious, but numerous enough that many thousands of collectors could participate and form a community.” (Proof of Punk: When Code Became Culture, in Collecting Art Onchain, 2025. p. 79.) The success of the 10,000 model was not about numbers, but about alignment - intention, participation, and visibility without force.

The network did not grow because it was engineered to win.

It grew because it was given space to exist.

In 2022, CryptoPunk #305 joined ICA Miami’s permanent collection, where it was presented alongside American Lady by Andy Warhol. Image credit: ICA Photographer, Bob Foster

Ownership, Absence, and Cultural Maturity

This becomes most visible when listening to collectors. In conversations for Collecting Art Onchain, nearly everyone either owned a CryptoPunk, cited one as formative, or expressed regret at not having acquired one.

That regret is often misread as financial. It is cultural.

What is mourned is not missed appreciation, but missed proximity to a moment when collective meaning was still fluid. CryptoPunks function as temporal markers - signals of presence during a formative phase. Their absence remains psychologically active. Even non-owners orient themselves in relation to them.

Imagine the world without them, on-chain culture would likely still exist, but its shape would be different. Identity might have emerged later, through more complex or similar systems. Community might have formed around utility rather than faces. Meaning would have accumulated unevenly, through isolated experiments rather than a shared early moment of learning.

What becomes clear is this: CryptoPunks mattered less as objects than as catalysts. They set network effects in motion that compounded over years, not weeks. Attention led to recognition. Recognition to belonging. Belonging to memory. Memory to culture. As Hall and Watkinson themselves describe, “We think of the Punks as primarily an interactive work. It gains importance and significance due to the interactions of the people and organizations that own them.” (Proof of Punk: When Code Became Culture, in Collecting Art Onchain, 2025. p. 85.)

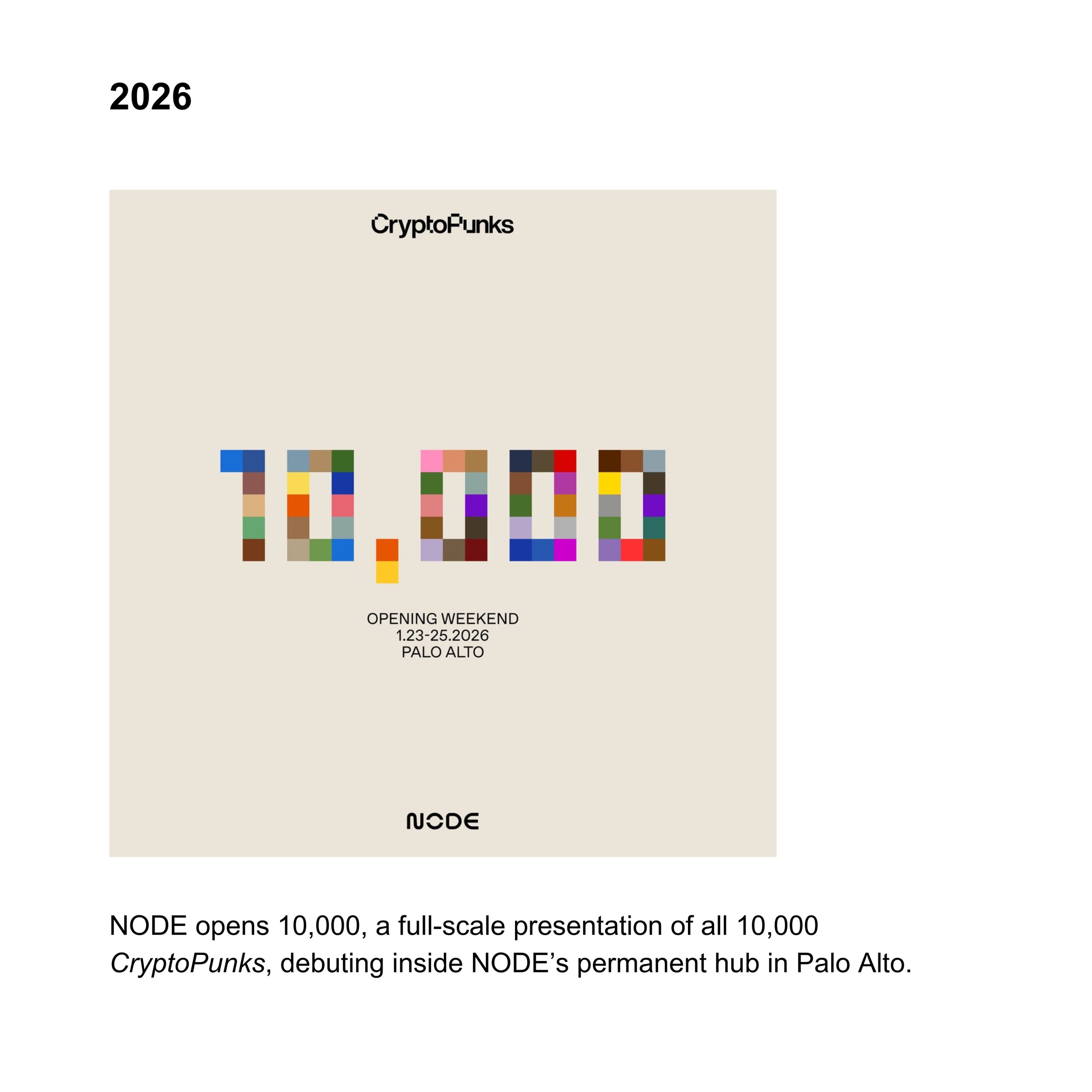

Seen this way, the emergence of custodial structures like NODE is not a rupture, but a consequence. Mature networked cultures begin to care for themselves — not to fix meaning, but to preserve the conditions under which meaning can continue to evolve.

CryptoPunks did not simply demonstrate a successful project.

They demonstrated what it looks like when a decentralized culture grows up.

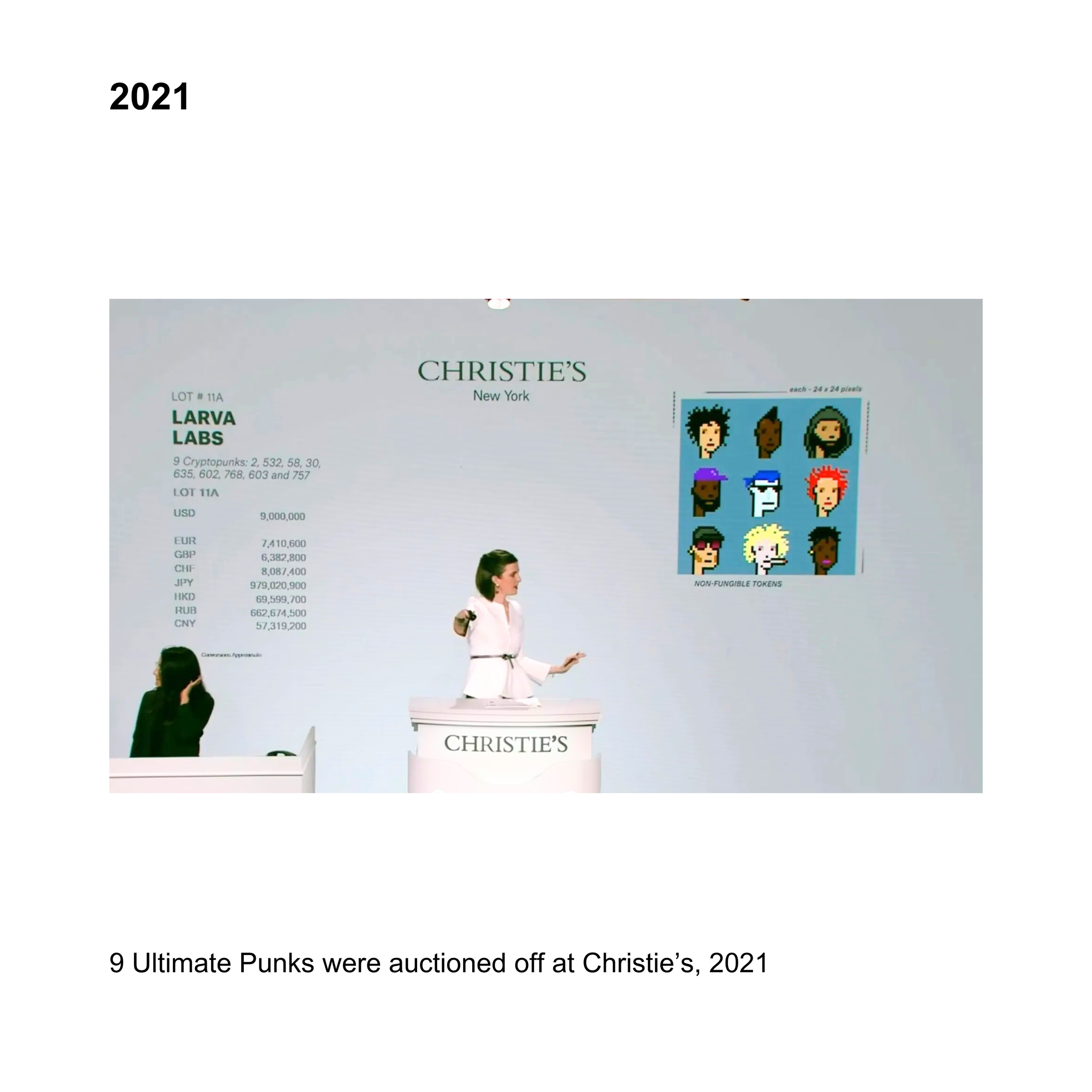

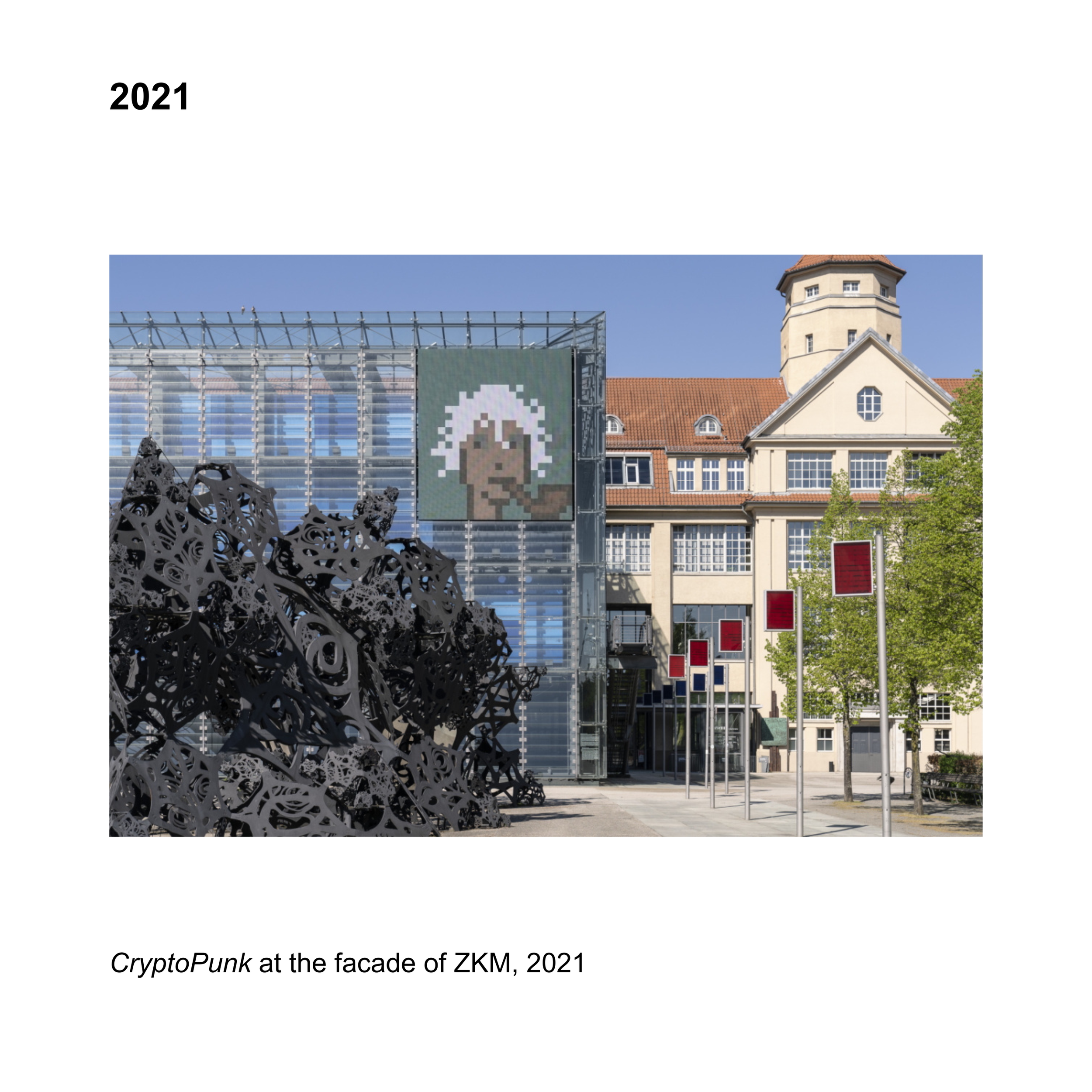

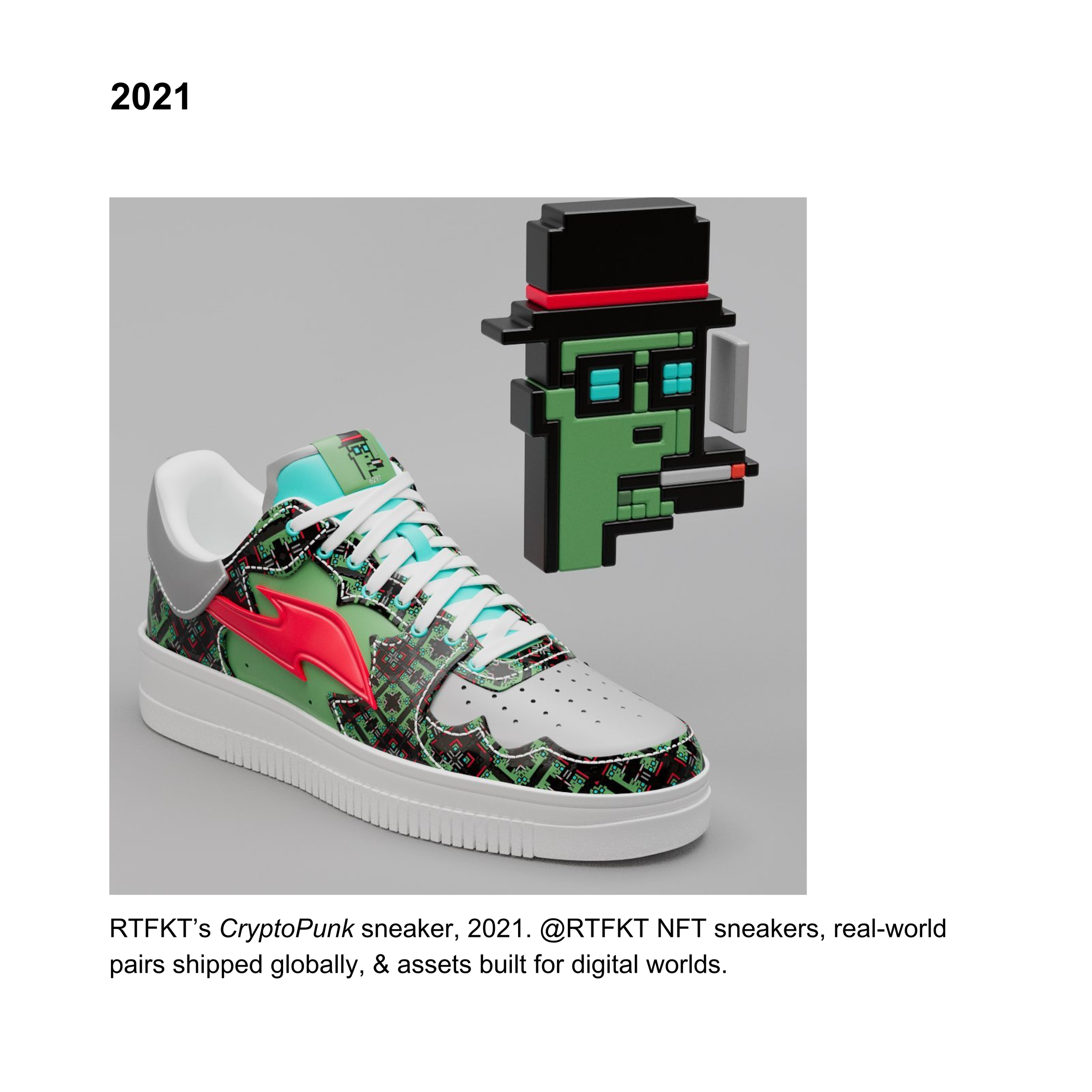

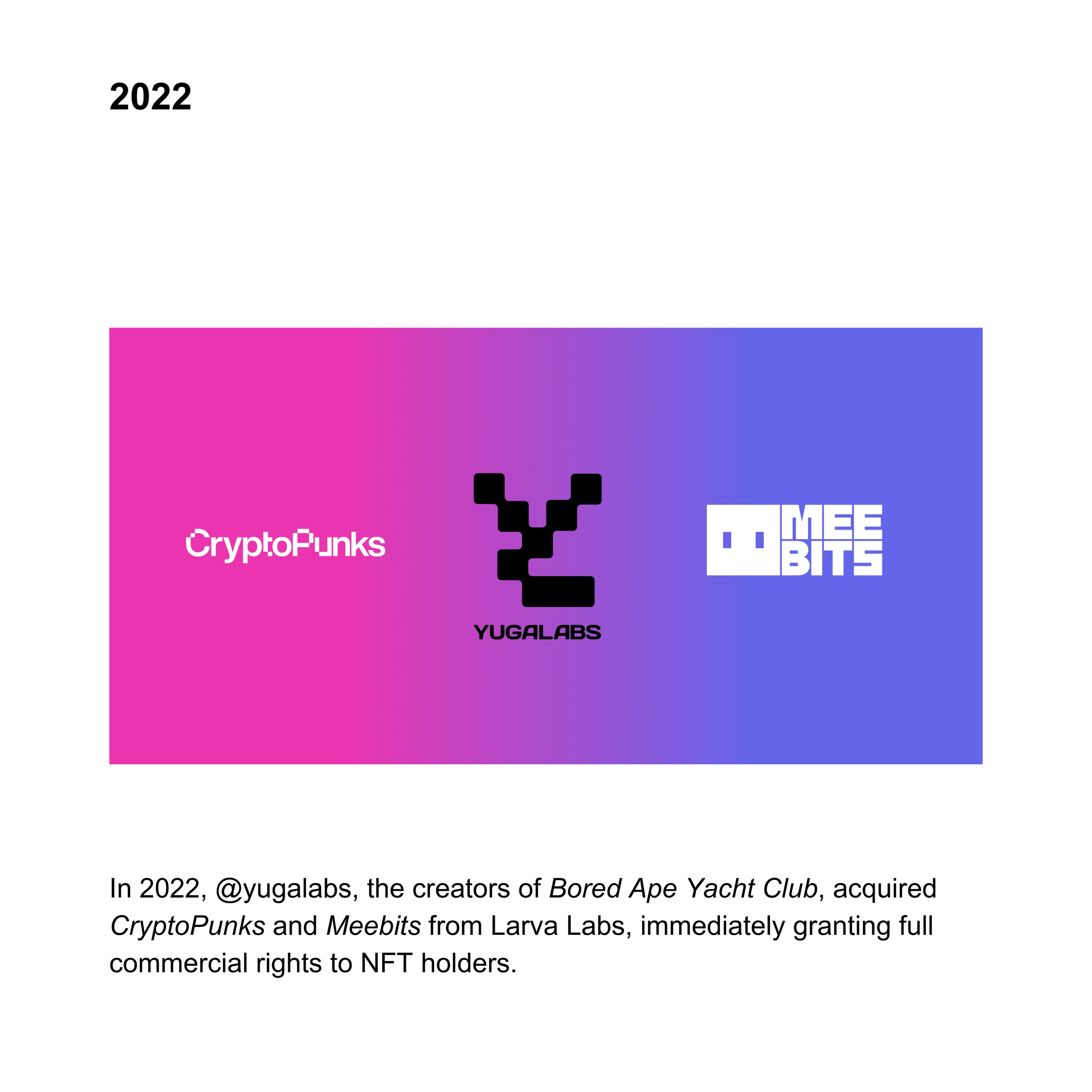

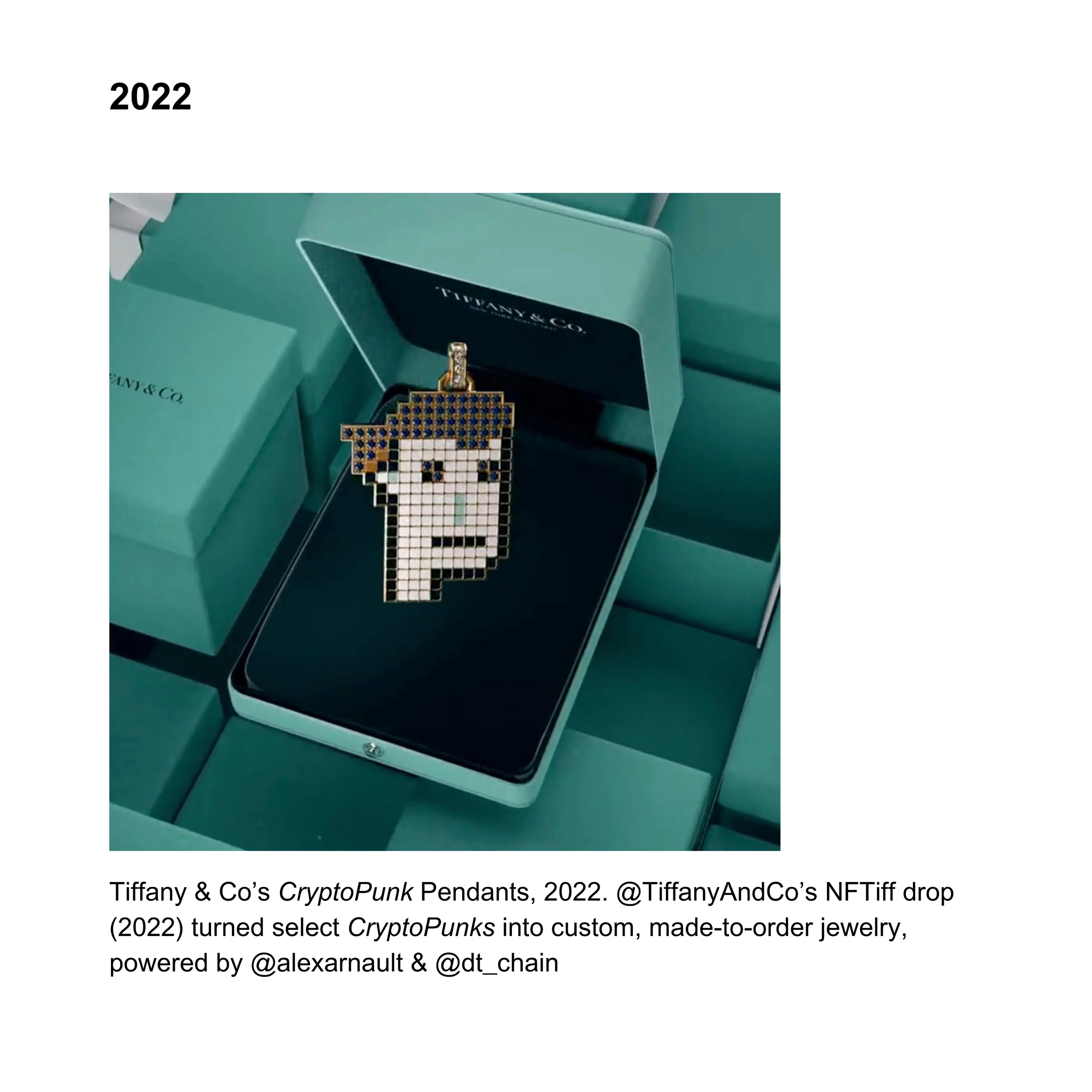

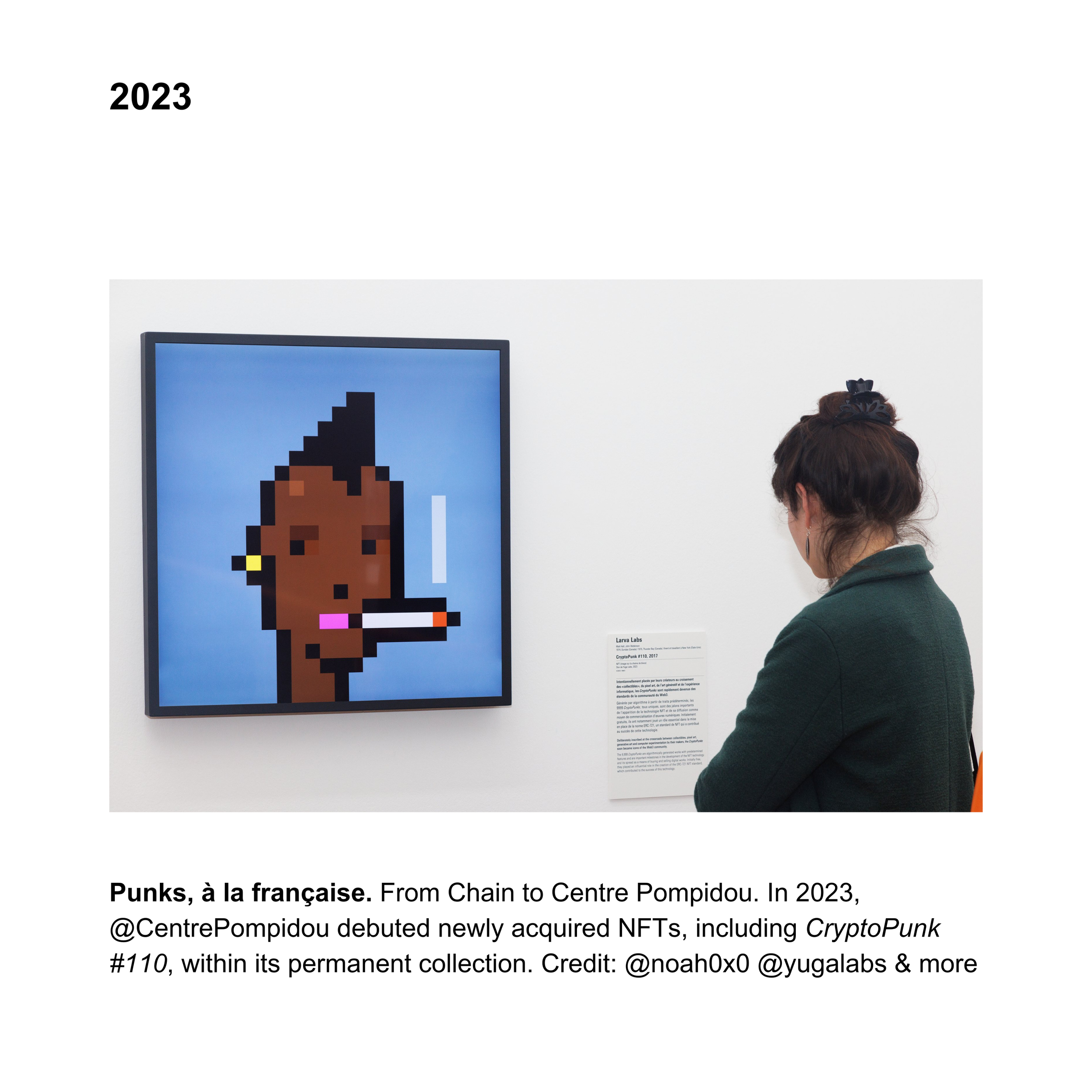

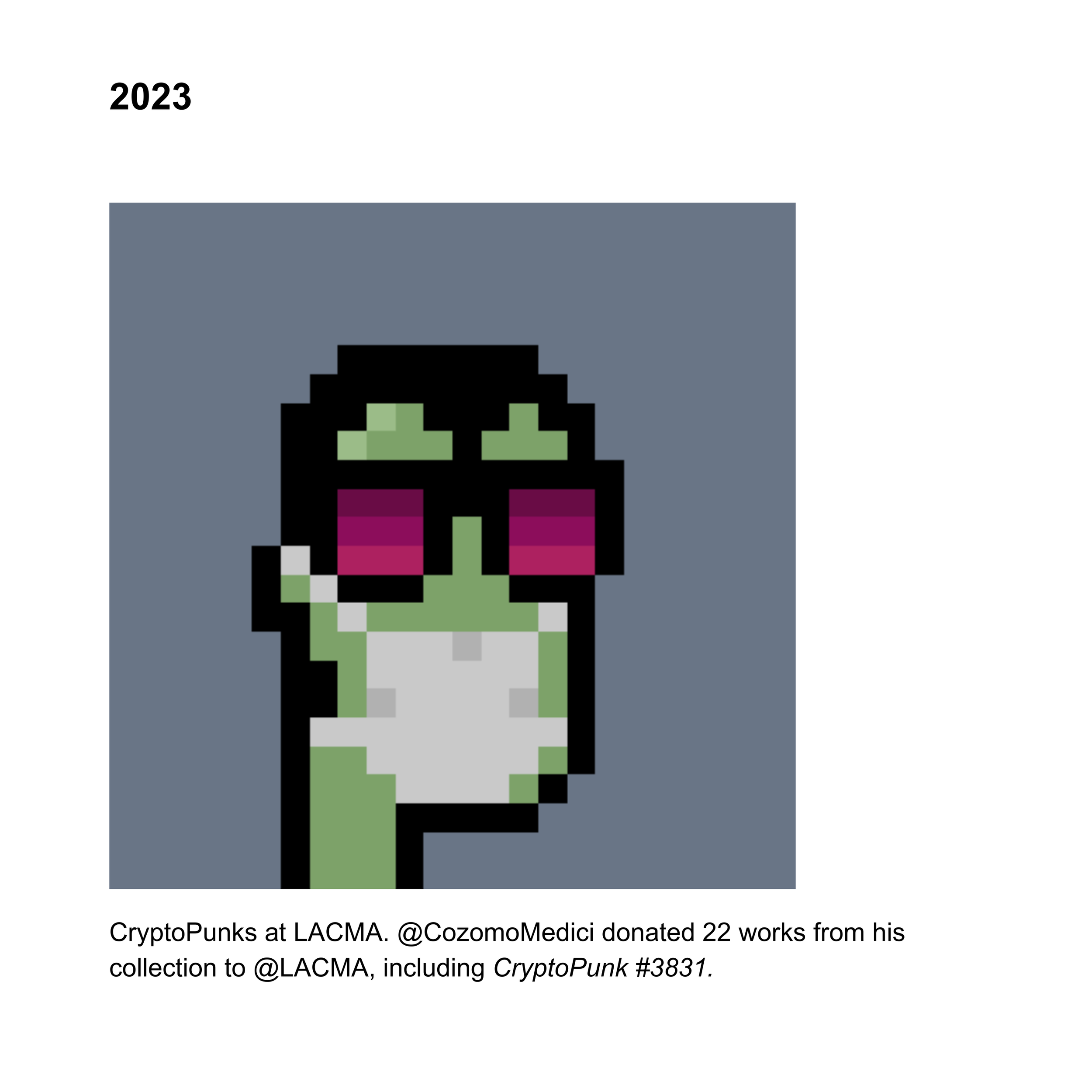

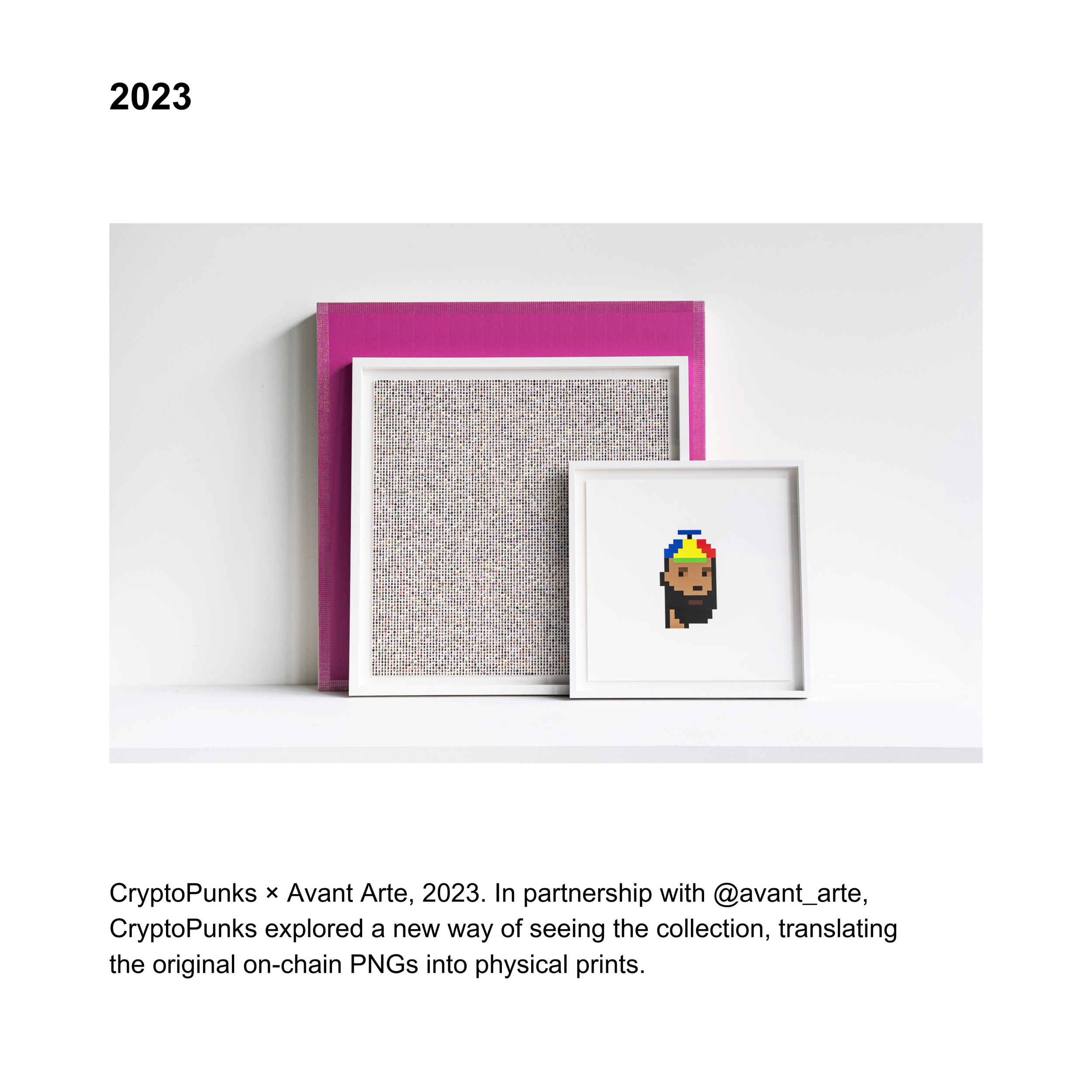

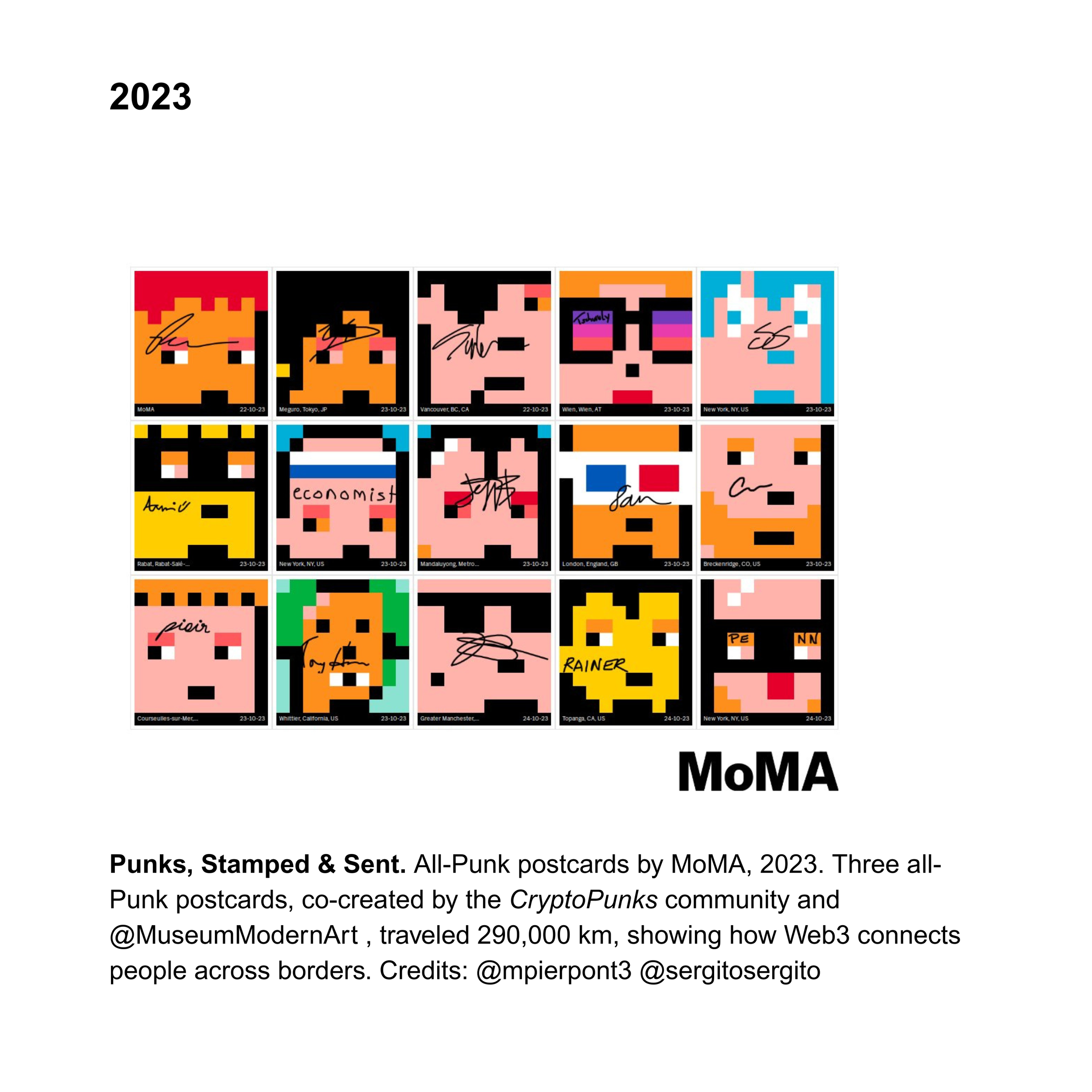

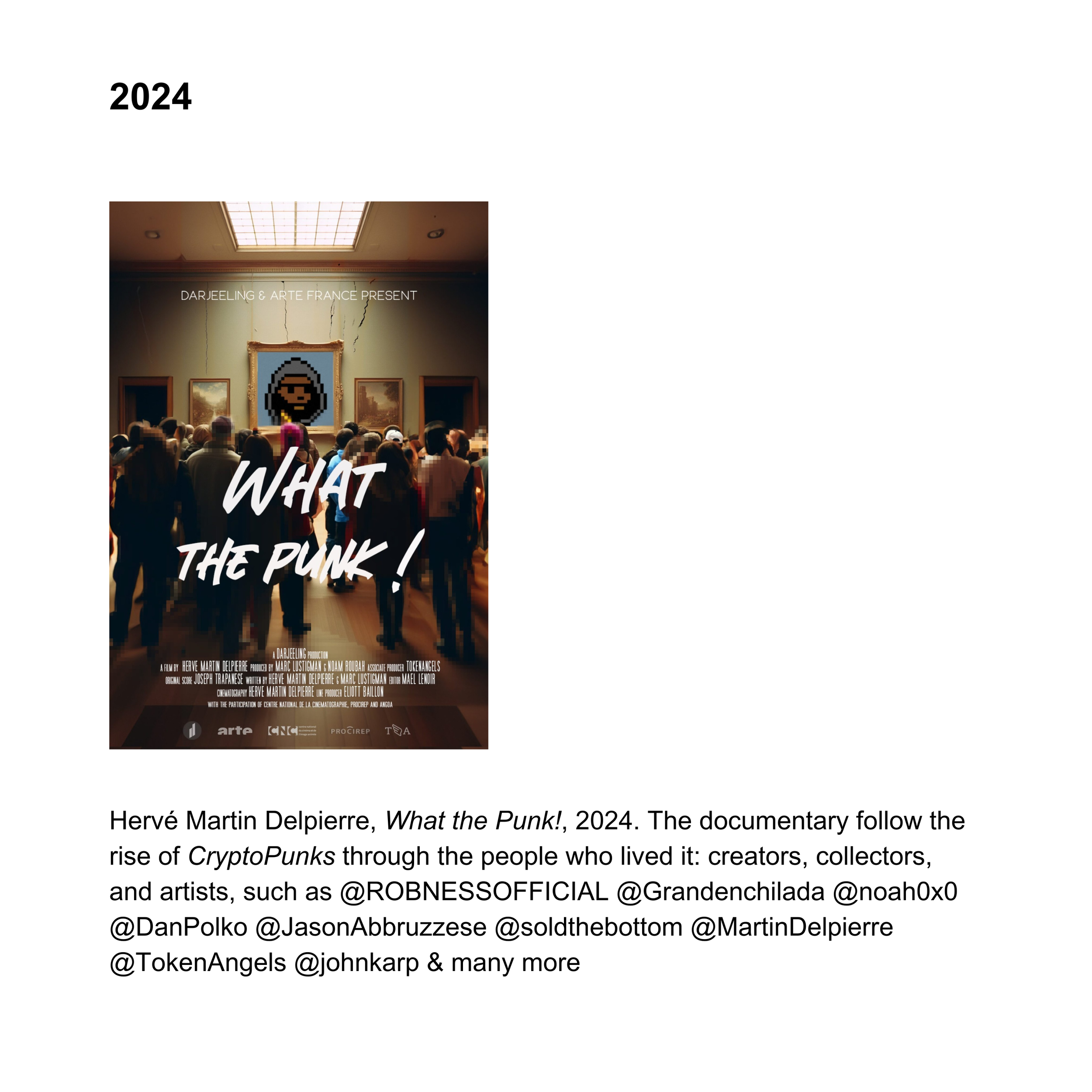

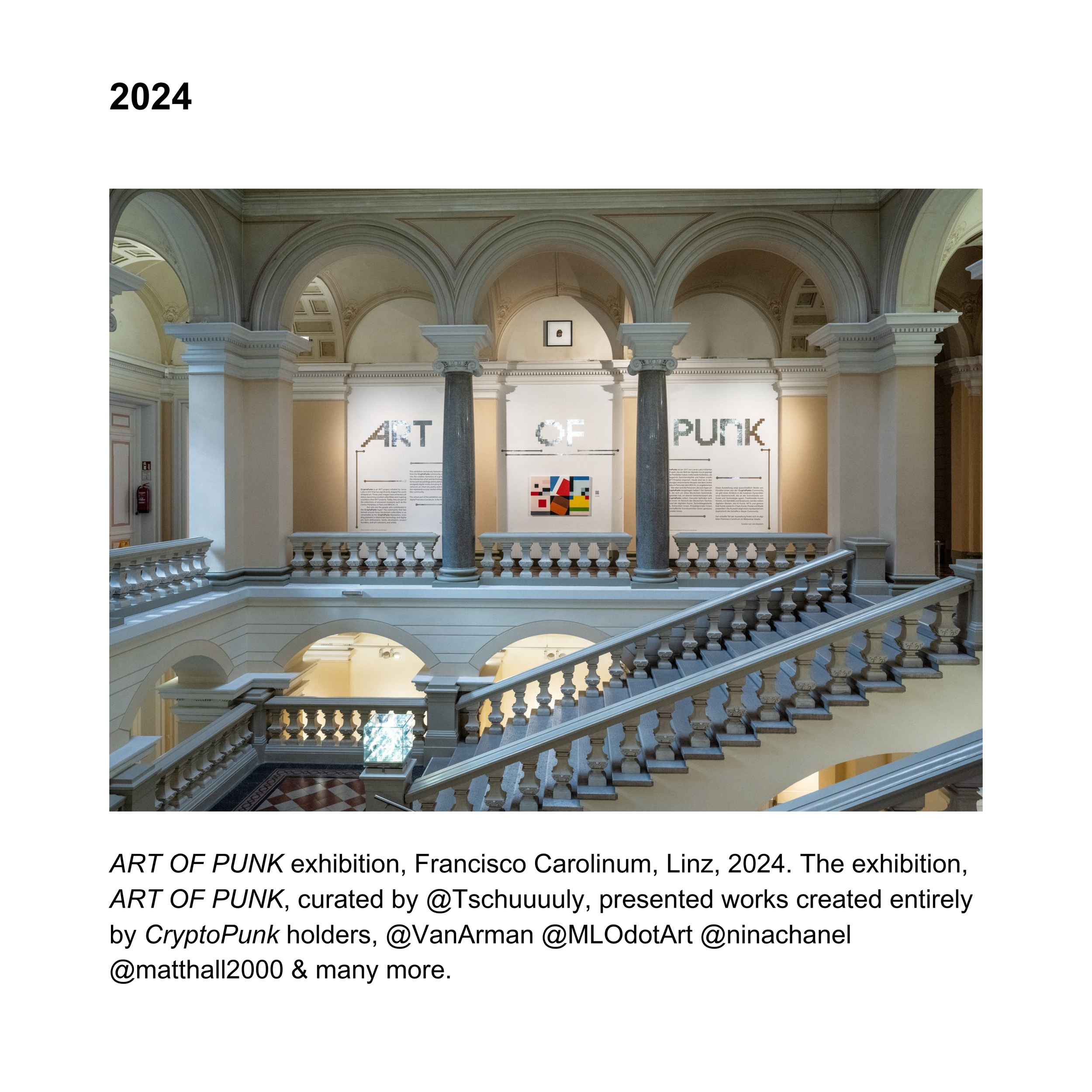

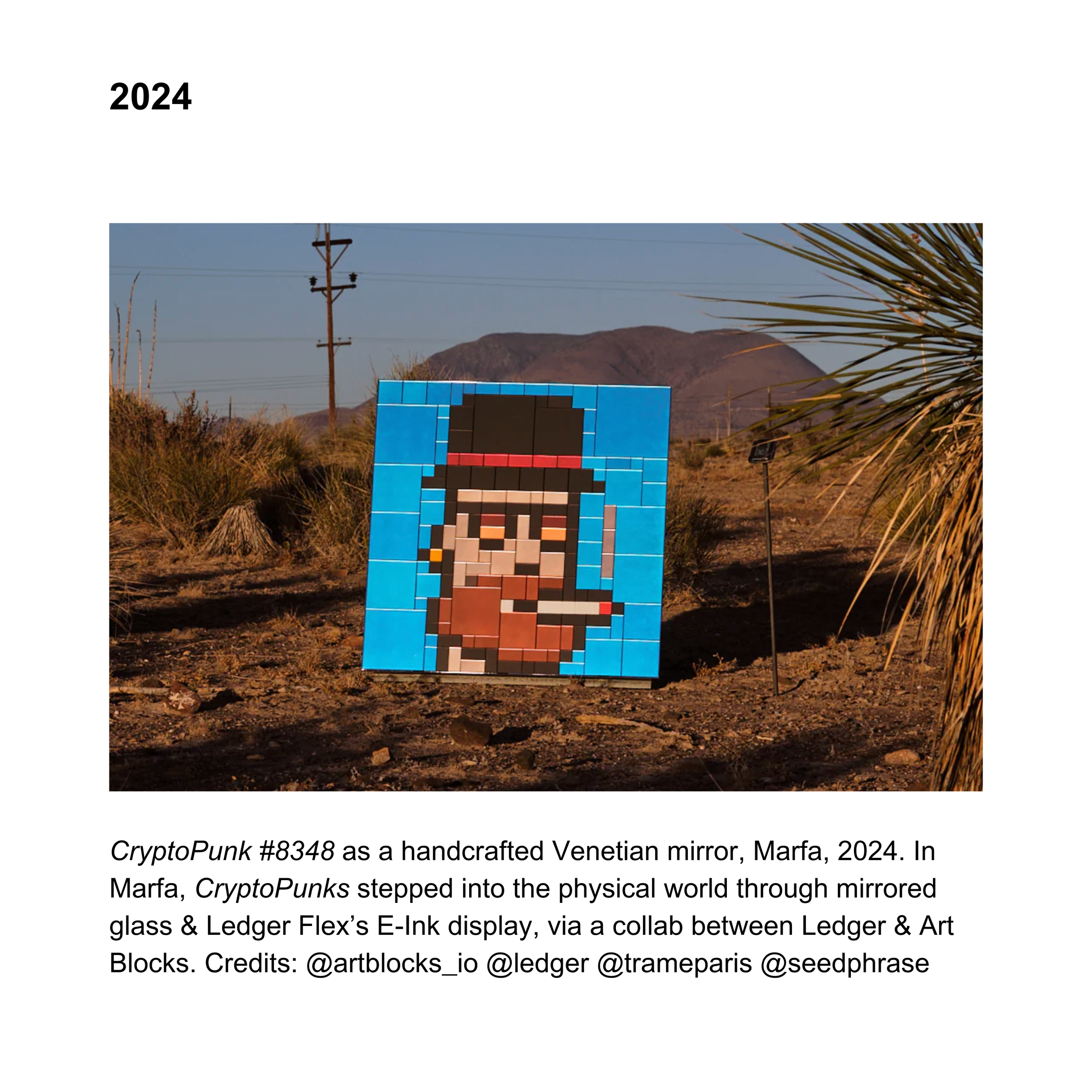

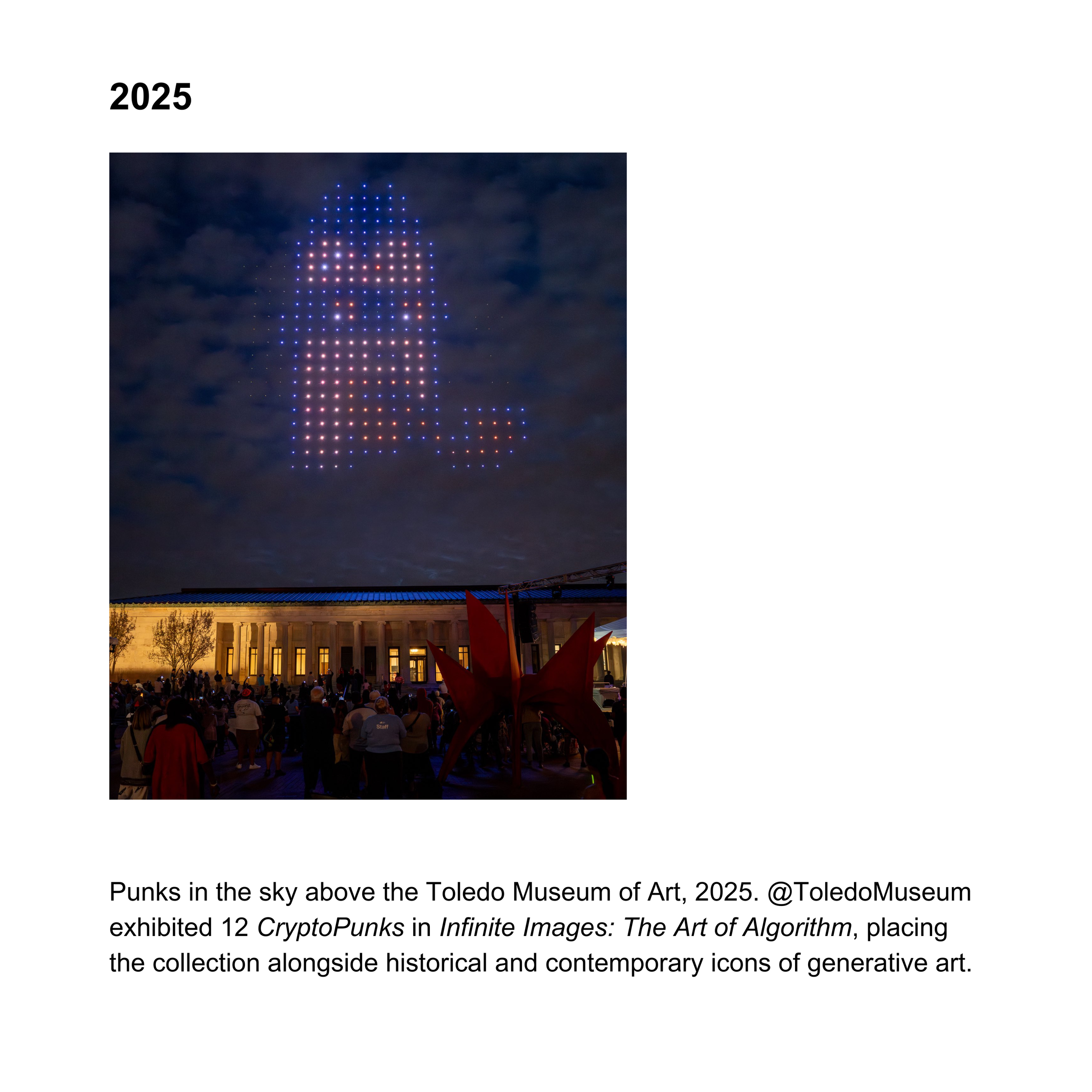

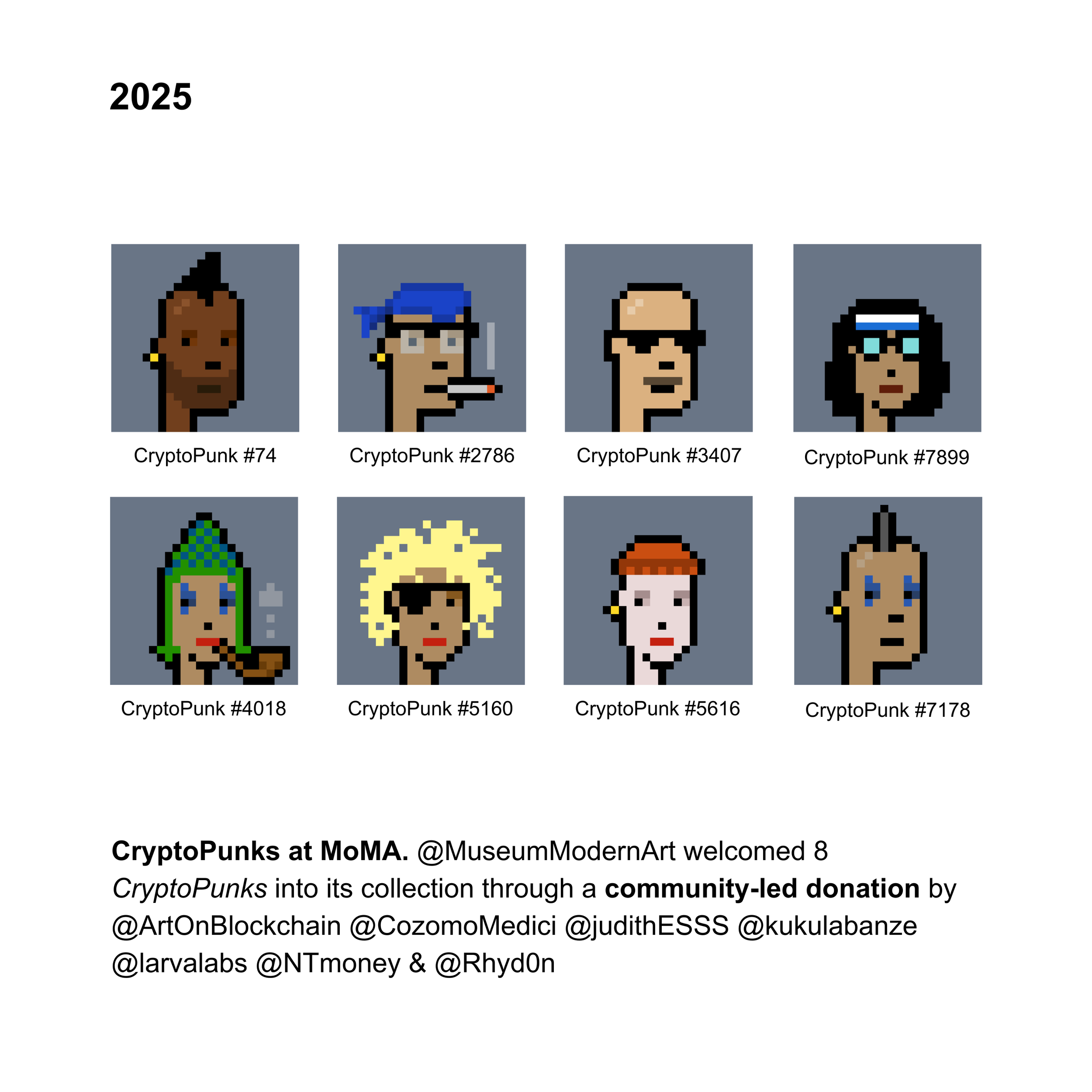

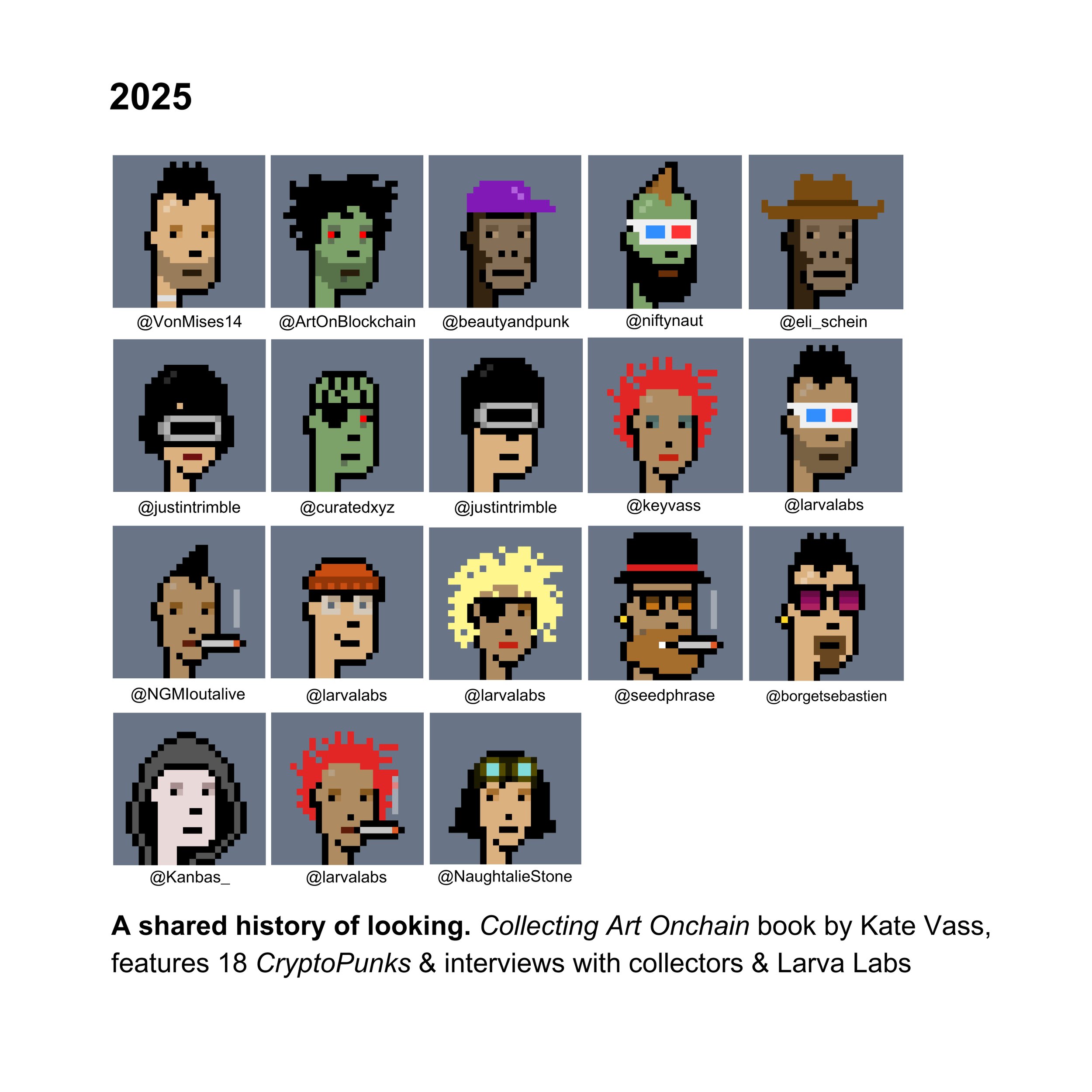

Some key milestones in the cultural life of CryptoPunks 2017-2026:

Disclaimer: This essay does not retrace the full technical or chronological history of CryptoPunks, nor the detailed formation of the NFT ecosystem around them. Instead, it focuses on how CryptoPunks came to be recognized, inhabited, and sustained as a cultural form, examined retrospectively through attention, participation, identity, and collective meaning.

A full, in-depth interview with Matt Hall and John Watkinson is published in Collecting Art Onchain, in the chapter “Proof of Punk: When Code Became Culture” (p. 70–87).

More information about the book can be found at: https://book-onchain.com/

✨ Culture Doesn’t Preserve Itself. Help Us Build the Infrastructure.

Your donation helps support the ongoing independent, non-profit initiative dedicated to exploring how digital art is written, contextualised, and preserved.

Contributions fund ongoing research, curatorial work, and archival infrastructure, ensuring that the art and ideas shaping this era remain accessible, verifiable, and alive for future generations on-chain:

Donate in fiat

You can contribute via credit card here:

https://www.katevassgalerie.com/donation

Donate in ETH

Send ETH directly to:

katevassgallery.eth - 0x56A673D2a738478f4A27F2D396527d779A1eD6d3

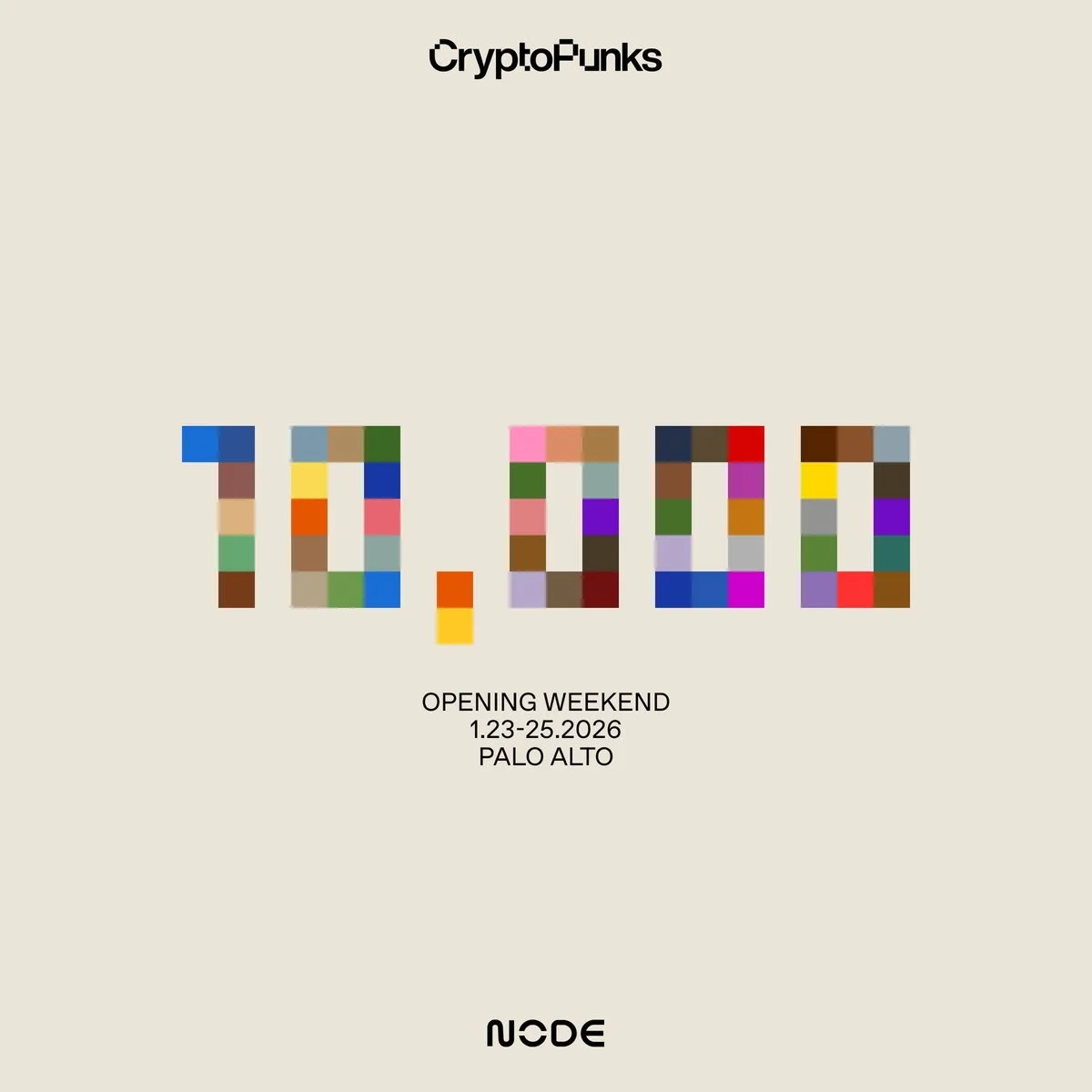

10,000 CryptoPunks – Opening weekend

1.23-25.2026

Palo Alto

NODE opens with 10,000, the first exhibition devoted to CryptoPunks, created by Matt Hall and John Watkinson (Larva Labs) in 2017. CryptoPunks is among the most influential works of digital art ever produced; it introduced a new paradigm for authorship and ownership online, inspired the Ethereum blockchain standard, and marked a cultural shift in how identity, provenance, and value can exist in purely digital form. 10,000 presents CryptoPunks as a living artwork: a self-running system whose marketplace is foregrounded as an integral part of the art – every offer, bid, sale, and transfer is both an economic event and an aesthetic one.

Learn more about the full weekend programme here:

Are We Doomed - or Simply Miscommunicating?

(XCOPY, Mixed Signals, and the Psychology of Seeing).

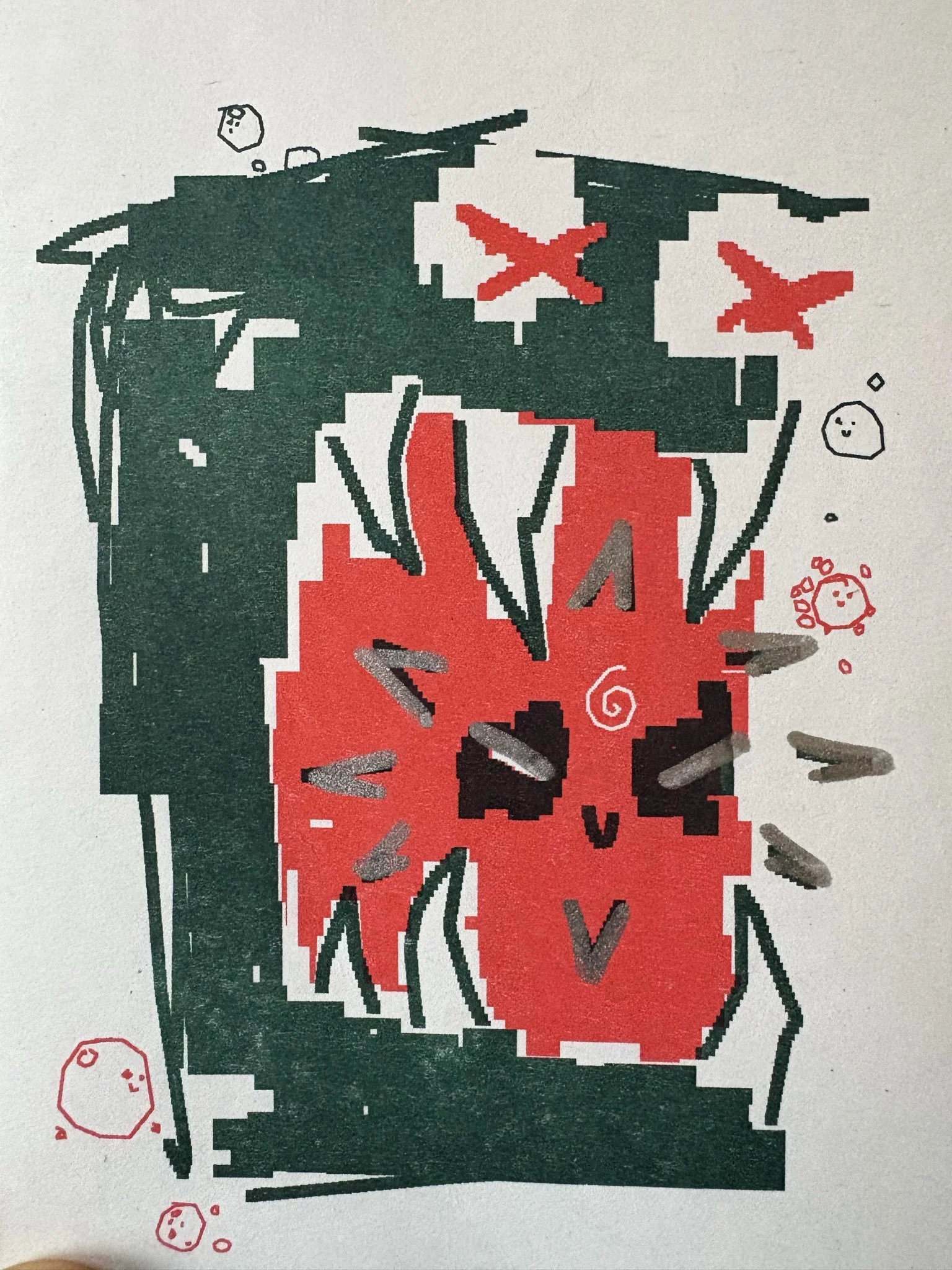

XCOPY, CryptoArtLand, 2020.

In the days following Art Basel Miami’s Zero 10 activation, an Observer article reignited a familiar standoff between Web3 and the traditional art world. On one side, Web3 participants argued- once again -that critics had “missed the point” of XCOPY’s work: its critique of systems, its intentional instability, its refusal to behave like art is supposed to behave. On the other hand, traditional critics insisted they had done nothing more than describe what they encountered: a laundromat installation, millions of free NFTs, and a spectacle that vanished almost as quickly as it appeared.

But this recurring debate misses the more interesting question.

The issue is not who is right.

The issue is whether any of us -Web3, institutions, critics, collectors- truly understand how XCOPY is being communicated, and how that communication shifts as it moves across contexts.

What looks like misunderstanding may, in fact, be a structural problem of transmission.

The Paradox of Displaying Non-Canonical Art

XCOPY’s art is often discussed in relation to entropy, unreliability, and systems collapsing under their own weight, frequently understood as reflecting the volatility, speed, chaos and repetition of internet culture itself. From the beginning, it existed in unstable conditions: distributed across ephemeral platforms, endlessly looped, circulating as files that felt disposable rather than fixed. Images repeated themselves, copied, saved, reposted, and reinterpreted.

His work did not invite slow contemplation in controlled environments; it thrived on friction, volatility, and misalignment. It resisted the mechanisms through which art typically stabilizes: archival coherence, institutional framing, and the gradual smoothing of edges that accompanies canon formation.

In this sense, XCOPY’s work was not merely anti-canonical in style.

It was anti-canonical in behavior.

Something feels askew about seeing XCOPY, in 2025, neatly displayed on wall-mounted screens inside a physical gallery. Presenting these works as a stabilized “timeline” within a clean white-cube setting risks softening the very instability that gives them their force. This is not a critique of the display itself, but a reflection on the viewer’s perception - especially when approaching an artist whose work was conceived to disrupt canonization rather than settle into it.

The SuperRare gallery, however, stands as a meaningful exception. It carries a particular legitimacy as a kind of homecoming: the platform where XCOPY minted his early 1/1 digital works. In this context, the exhibition, Tech Won’t Save Us, reads less as institutional containment and more as an evolution- both of SuperRare and of the artist -tracing a trajectory from the digital canvas into physical gallery space.

Rather than neutralizing the work, the setting reveals an interesting expansion of XCOPY’s practice, and of the platform itself, as both move beyond their original digital parameters.

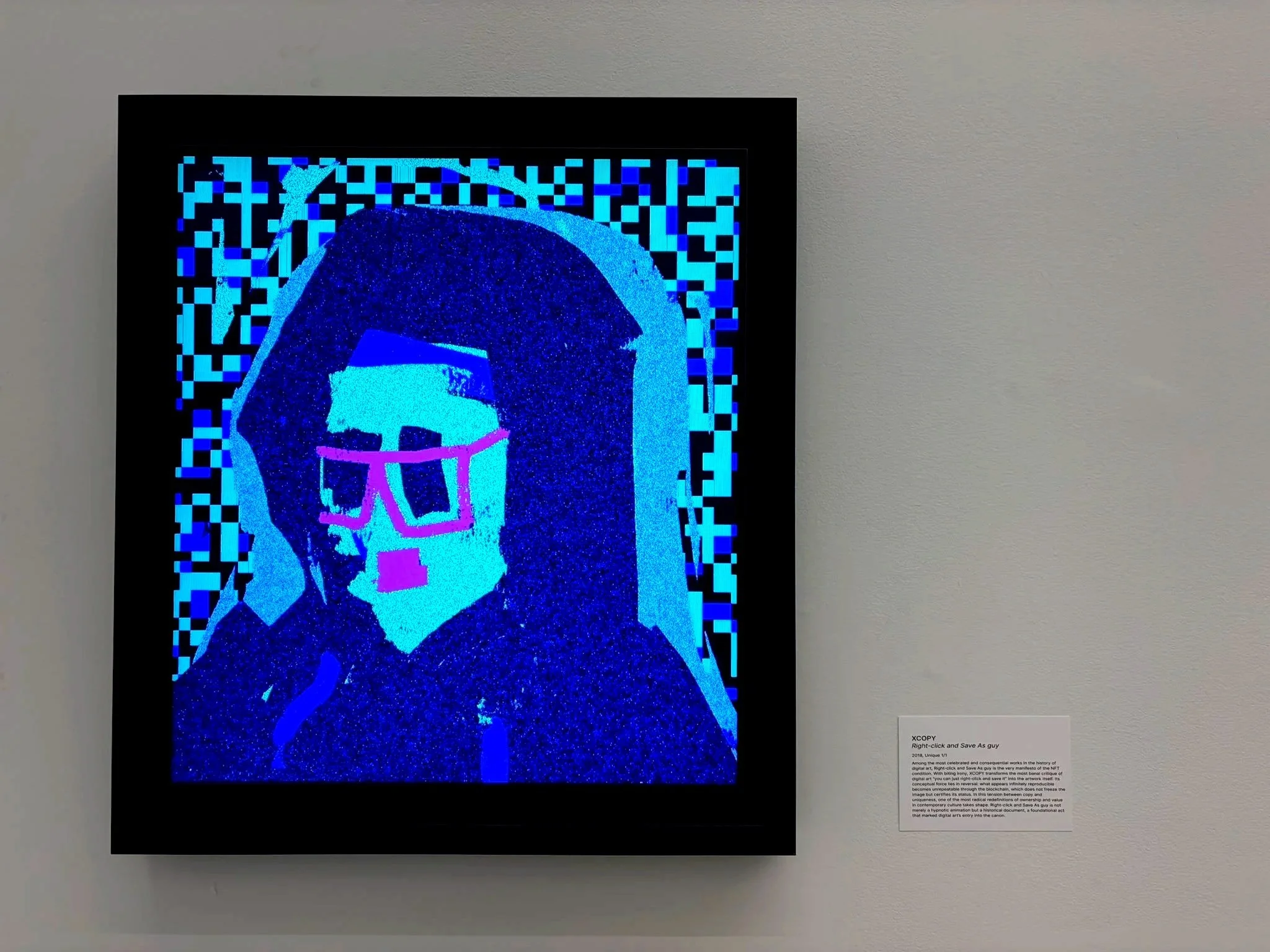

XCOPY, Right-click and Save As guy, 2018, exhibited in Tech Won’t Save Us, organized by SuperRare in collaboration with The Doomed DAO, Offline Gallery, New York.

The question is not whether this form of presentation is legitimate.

The question is more fundamental:

What does it mean to canonize anti-canonical art?

Canonization is one of the most powerful context-shifts an artwork can undergo. To canonize a work is to relocate it, to place it within new spatial, cultural, and interpretive frameworks that actively shape how it is seen.

In this sense, canonization cannot be separated from a deeper issue: how artworks change meaning as they move across contexts.

So when XCOPY appears in a white cube gallery, an underground basement, and a global art fair within the same month, radically different interpretations are inevitable.

The work has not changed.

The contexts have.

The message fractures because framing alters how the work is perceived.

XCOPY, Loading New Conflict... Redux 5, 2018.

Perception Is Never Neutral

Psychology offers a useful lens here. We do not encounter artworks as blank slates. Perception is filtered through expectation long before the eye meets the object. Cognitive science refers to this as top-down processing: the mind supplies meaning in advance, filling gaps with assumptions, cultural cues, and prior beliefs.

In other words, we rarely see what is.

We see what we expect to see.

As art historian Ernst Gombrich famously observed, there is no such thing as the innocent eye. Seeing is never neutral; it is conditioned by habit, context, and belief.

From the early twentieth century, artists and theorists have challenged the idea that an artwork carries a stable meaning independent of where and how it is encountered. Marcel Duchamp’s readymades marked a decisive turning point. They demonstrated that placement alone could transform interpretation.

Context was no longer a neutral backdrop.

It became an active producer of meaning.

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917. Source: tate.org.uk

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, this expanded into a broader awareness of framing. Daniel Buren, in essays such as The Function of the Museum (1970), argued that museums and galleries do not merely display artworks, but they also actively shape how works are perceived, valued, and understood.

Meaning does not reside solely in the object. It emerges at the intersection of work, space, and expectation.

This becomes even clearer with digitally native works. They often accumulate meaning, value, and interpretation before they ever enter a physical exhibition space. The gallery or museum is not their point of origin, but one context among many. When they appear in physical form, they do not arrive as neutral objects. They arrive already shaped by prior circulation, community belief, and expectation.

What emerges is not a single meaning, but a series of encounters, each shaped by the conditions in which the work is met.

New York: “Tech won’t save us,” community might.

SuperRare was among the first environments in which XCOPY’s 1/1 works were minted, circulated, and meaningfully understood. Hosting Tech Won’t Save Us in New York, in collaboration with The Doomed DAO, is not an act of appropriation but of continuity -a homecoming that honors where both the artist and the platform began, while acknowledging how profoundly each has evolved.

Seen through this lens, the apparent tension between XCOPY’s destabilized, glitch-driven aesthetic and the gallery’s institutional calm becomes reflective rather than adversarial. What once existed, as often described, as raw disruption now carries history. What once resisted framing now tests it. The glitches remain, but they arrive with memory. The instability is intact, yet it is viewed through the accumulated weight of time, community, and belief.

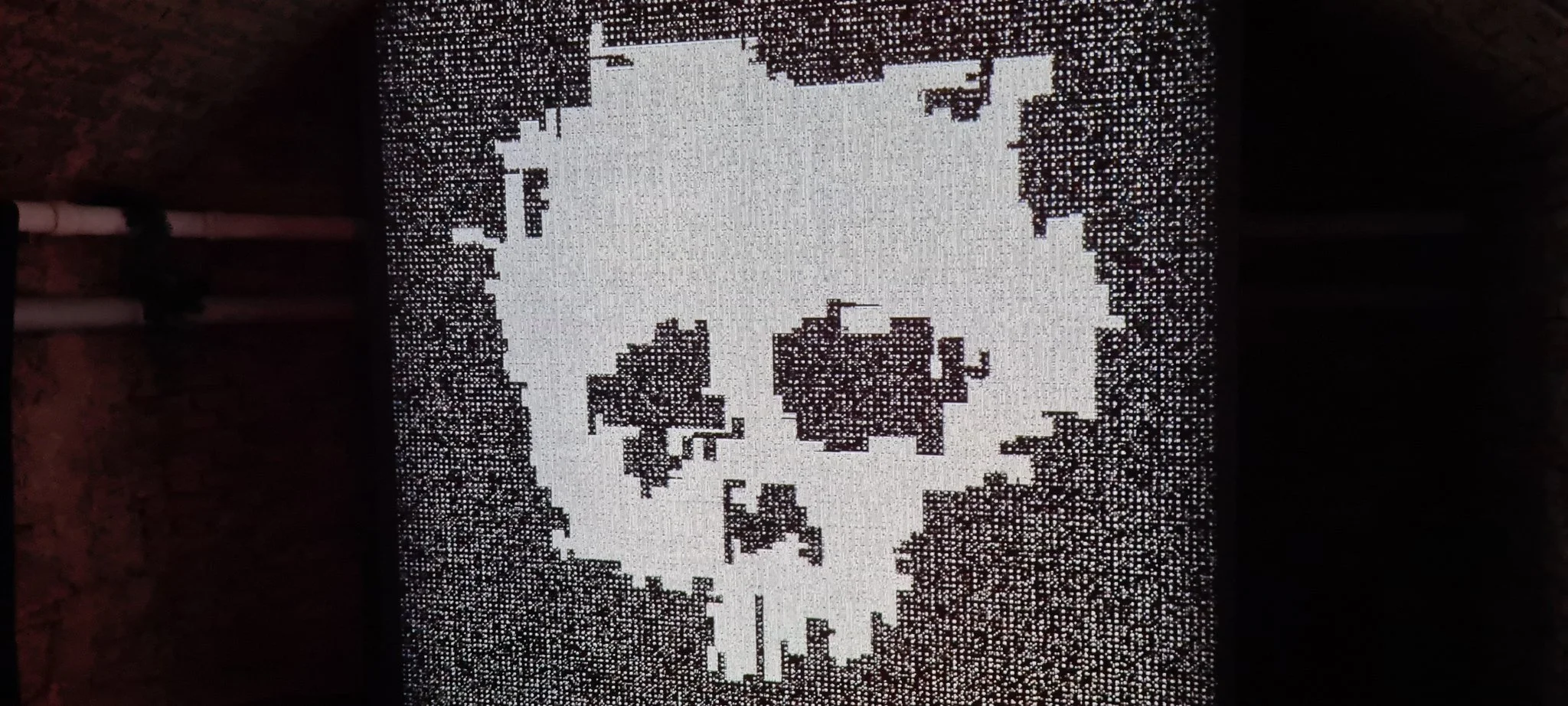

XCOPY, The Doomed (Mono), 2019, exhibited in Tech Won’t Save Us, organized by SuperRare in collaboration with The Doomed DAO, Offline Gallery, New York.

The exhibition Tech Won’t Save Us, organized by SuperRare in collaboration with The Doomed DAO, Offline Gallery, New York.

Psychologically, the gallery still activates art-historical expectation. Viewers arrive prepared to analyze, contextualize, even canonize. But here, that expectation becomes part of the work. The framing suggests permanence; the imagery resists it. The friction is not a flaw -it is evidence of change.

The exhibition’s real gravity, however, lies beyond the screens. XCOPY, SuperRare, The Doomed DAO, and a deeply committed community occupy the same space, collapsing distance between artist, platform, and audience. The artwork becomes relational not because it demands interaction, but because it is inseparable from the network that carried it forward. In this moment, the network is no longer abstract-it is embodied.

What shifts in this context is not the content of the work, but its function. The work enters the white cube already carrying its own history, beginning to operate as a cultural artifact. XCOPY’s disruption is no longer only an act of refusal, it becomes an object of sustained attention. Volatility is slowed. Instability is held long enough to be examined. The work does not lose its critical force, but it changes how it is experienced, from immediate disruption to something viewers can stay with and examine.

Perception still diverges:

Some viewers see canonization.

Some see contradiction.

Some see celebration.

All are correct.

And perhaps that, too, is a measure of how time changes us—not only the artist and the platform, but the way we learn to see, and what we believe art should be.

Vienna & Melbourne: When Art Becomes a Signal Rather Than an Object

The satellite exhibition of Tech Won’t Save Us, Vienna, Austria. Organized by The Doomed Dao members @nessnisla.eth, @_mp9x

If New York renders XCOPY a cultural artifact, Vienna treats him as a transmission.

As a satellite exhibition of Tech Won’t Save Us in Vienna, the works are installed in a basement, where screens flicker against concrete walls indifferent to institutional decorum. Nothing in the space instructs the viewer on how to behave or what to think. Meaning is not ‘curated’; it is encountered.

Here, framing bias weakens. Without cues that signal “high art,” viewers generate interpretation more freely. A screen underground triggers adjustment rather than analysis. The work feels discovered, not presented.

In this environment, the work aligns closely with the visual language and cultural conditions from which it originally emerged. The absence of polish and institutional cues allows the work’s instability, discomfort, and refusal to surface more directly.

Responses vary. Some experience nostalgia - echoes of early internet culture. Others sense refusal-art that won’t resolve into comfort. Some dismiss it entirely as “screens in a basement.”

The file, of course, is unchanged.

Only the context shifts - and with it, the meaning.

Art Basel Miami: Expectation, Misperception, and the Laundromat

Art Basel Miami introduces the most acute perceptual conflict: XCOPY’s Coin Laundry, where more than 2.3 million free NFTs were claimed, all but one designed to self-destruct over the next ten years. Coin Laundry was conceived specifically for this scale and setting, where mass participation, speed, and disappearance are not side effects but core elements of the work.

Within Web3, the work was largely read as critique—a dismantling of value stability, liquidity theater, and the fetishization of ownership. Within the traditional art world, it appeared to confirm long-held suspicions: abundance without scarcity, spectacle without substance, volatility masquerading as meaning.

This is confirmation bias at work.

XCOPY, Coin Laundry, 2025, presented by Nguyen Wahed at Art Basel Miami.

People interpret information in ways that reinforce what they already believe. XCOPY dissolves value systems; critics perceive disposability. Their interpretation is not wrong - it is partial. They are not, as many claim, ‘missing the point’; they are encountering it through a familiar psychological schema.

Scale does not distort meaning; it accelerates it. When a work reaches millions, interpretation compresses, and familiar expectations assert themselves more quickly. The intention remains intact, but the conditions of reception shift.

Learning How to See — and How to Connect

The challenge is not how to show XCOPY’s work.

It is how to connect it to audiences who are not already native to its language - who do not come from crypto, blockchain, or online network cultures.

XCOPY’s practice was never built to explain itself to everyone at once. It emerged from specific conditions: digital scarcity, speculative economies, on-chain identity, and communities that understood value as volatile, temporary, and often performative. When that work enters broader cultural spaces, it encounters viewers who lack not intelligence, but context.

Perspective matters.

Expectation matters.

Experience matters.

Meaning does not fail here - it collides.

XCOPY’s work operates as conceptual art, but its concepts are encoded in network logic rather than art-historical language. For those outside that logic, the signal can register as noise. This does not invalidate the work; it reveals the gap between worlds that are now colliding.

XCOPY, the fuck you looking at?, 2020.

So the question becomes: can we learn to encounter the work without demanding immediate comprehension?

Children do this naturally.

They do not need fluency in systems to respond, they are moved by intuition. They experience first. They remain open to confusion. They allow meaning to form over time rather than insisting on resolution.

Perhaps this is the mode of viewing XCOPY requires - not expertise, but suspension. A willingness to step back from expectation and let the work exist before asking it to perform.

If so, XCOPY’s practice is not about cleanly bridging worlds or translating itself into familiar terms. It exists in advance of mass understanding - inhabiting networked futures that will inevitably spill into physical reality, but never on stable terms.

The work does not ask to be celebrated.

It does not ask to be agreed with.

It asks only to exist long enough to be encountered- before perspective, belief, and expectation decide what it is allowed to mean.

Yet gathering, curating, narrating, canonizing - these are institutional actions no matter who performs them. Decentralization dissolves authority only for it to quietly reassemble elsewhere, often inside a Discord server.

The Doomed DAO does not resolve this tension; it holds it. It attempts to preserve entropy where systems naturally seek permanence. XCOPY never promised stability, longevity, or preservation.

A noble contradiction. In other words -

Very XCOPY ;)

xxx

Disclaimer

This text does not claim to define XCOPY’s intentions. The aim of this article is not to explain XCOPY, but to examine how meaning shifts through context, framing, and viewer perception as the work moves across platforms, spaces, and audiences. What is described here is not what the work is, but how it is seen.

Credits & Congrats

Strong work by all who shaped XCOPY’s work across contexts and cities:

New York — @SuperRare, @_MP9X and the whole @TheDoomedDAO (Tech Won’t Save Us)

Vienna — the satellite organizers who embraced friction and let the work function as signal, not object

Art Basel Miami — @artbasel @zero10art (Coin Laundry)

Melbourne & beyond — independent curators and local teams continuing to test digital art in the wild.

Well done to everyone involved.

Physical card, signed by XCOPY, distributed at his solo exhibition Tech Won’t Save Us at Offline Gallery, New York.

★attention economy: Beeple’s Regular Animals — Who’s a Good Dog? Whoever Gets the Most Attention.

A deep dive into how attention—not art—creates value in Web3. Featuring a case study on Beeple’s Regular Animals and the psychology behind engineered virality.

Attention is a strange currency. The more information we receive, the less we can hold. Psychologists warned this decades ago: overstimulation erodes focus; cognition collapses under overload. Yet we keep reacting — faster, louder, more impulsively.

My last post made this painfully clear.

It generated discussion, outrage, agreement, confusion — everything except one thing: very few people actually read the full article.

Without time, slow reception, or attention to detail, no one can form a real opinion or offer meaningful critique. And that, precisely, is the point.

The most valuable currency today isn’t gold, oil, or even Bitcoin. It’s attention — the invisible architecture determining what becomes visible, valuable, celebrated, or quietly erased.

René Magritte, The False Mirror, 1928. A literal diagram of the modern internet: the eye doesn't see reality; it reflects the system back at itself. Image source: moma.org

In a world drowning in information and starved of cognition, attention is not just scarce — it is weaponized.

Psychologists warned that attention collapses under overload. Economists warned that scarcity creates markets. Today, culture forms inside the two.

Whoever shapes attention shapes narrative. Whoever shapes narrative shapes the future.

Open X and within seconds you’re pulled into a storyline you never chose — not an artwork, not an idea, but a frame engineered to feel organic.

Hito Steyerl, How Not to Be Seen, 2013. A manual for surviving the visual regime. Steyerl shows what most people still refuse to admit: images aren't just pictures — they're systems of power. They compress social forces into a single frame. Image source: moma.org

Most people don’t form opinions independently — not from lack of intelligence, but because independent judgment requires three things modern culture erodes: time, context, resistance.

It’s easier to mirror what appears “liked” than risk thinking differently. And when someone diverges, the crowd rushes in to “correct” them — social pressure disguised as consensus.

Behavioral psychology has documented this for decades: when uncertainty is high, humans outsource judgment to the group. Digital art, still lacking stable institutions or literacy, amplifies this effect.

Those who command or manufacture attention now determine more than price. They determine cultural reality itself — what is seen, forgotten, declared important, or omitted entirely.

Abundance vs. the Limits of the Mind

Herbert Simon captured our era perfectly: “A wealth of information creates a poverty of attention.”

Information can scale infinitely. The mind cannot.

Pak, The Merge, 2021. Pak's highest-selling NFT, generating $91.8 million. The work is one of the best expressions of how attention becomes value. The supply of the artwork increased as more people bought “mass” during the sale — meaning the artwork literally grew through attention. Image source: barrons.com

Behavioral economists call this the attention budget: a cognitive limit beyond which every additional input forces the brain to neglect something else. When information grows exponentially and attention does not, scarcity emerges — not of capital or objects, but of focus.

Where scarcity emerges, markets form. And in attention markets:

• what stands out overwhelms what matters

• visibility becomes shorthand for value

• velocity outruns understanding

Digital culture is frantic by design. Platforms scale speed, not meaning. Web3 simply added financialization.

When the system rewards immediacy, depth becomes a risk.

Attention as a Tradeable Asset

Nam June Paik, TV Buddha, 1974. Paik's recursive loop between observer and machine symbolizes a contemporary self-reinforcing cycle of attention: a recursive loop of watching ourselves watching ourselves. Image source: pbs.org

Metrics like likes, retweets, follower counts, wallet trackers, and “top sales” dashboards became market indicators → indicators became liquidity → liquidity became narrative.

A reflexive loop emerged:

Attention lifts prices.

Rising prices attract attention.

Attention endorses the narrative.

Narrative legitimizes value.

George Soros described this in reflexivity theory; behavioral economists map the same pattern in speculative cycles. Perception becomes reality long before reality is understood.

In Web3, this loop runs at hyperspeed. Not a bug — the design.

The Psychology Behind Reflexive Culture

Gustave Le Bon, The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind, 1895. Le Bon's diagrams of crowd behavior illustrate how individuals become reflexive and irrational under social signals. Image source: amazon.com

Consumer behavior research shows that human cognition relies on fast heuristics, especially under uncertainty. Digital art — new, unstable, lightly contextualized — is the perfect breeding ground for these biases.

We are neurologically wired to prioritize:

novelty (dopamine response)

emotion (amygdala activation)

social validation (the social proof heuristic)

urgency (scarcity effect)

repetition (the mere-exposure effect)

Web3 triggers these on a continuous loop:

Quick cues override slow thinking (Kahneman’s System 1 dominates System 2).

Collective enthusiasm substitutes for personal judgment.

FOMO compresses decision-making time.

People align with what feels socially safe rather than what feels true.

In such an environment, independent taste becomes a high-cost activity. Most people, rationally, choose the alternative: they follow the signal.

The louder something is celebrated, the more “true” it feels — not because it has been understood, but because our cognition is structured to avoid social and cognitive friction.

This is not stupidity. It is psychology. It is economics.

And in Web3, it is infrastructure.

★ Case Study: Beeple’s Regular Animals. Who’s a Good Dog?

(A short analysis of attention economy dynamics — not a review of the artwork itself.)

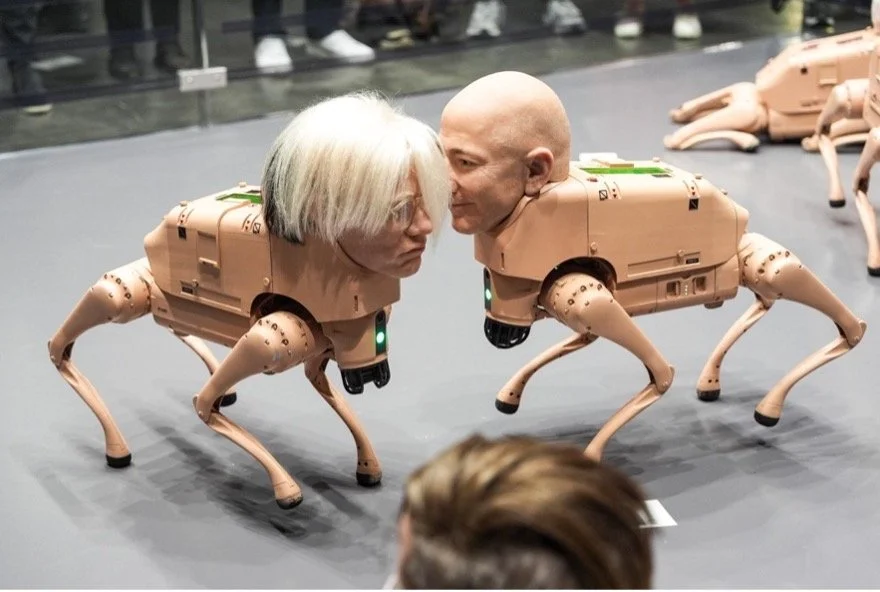

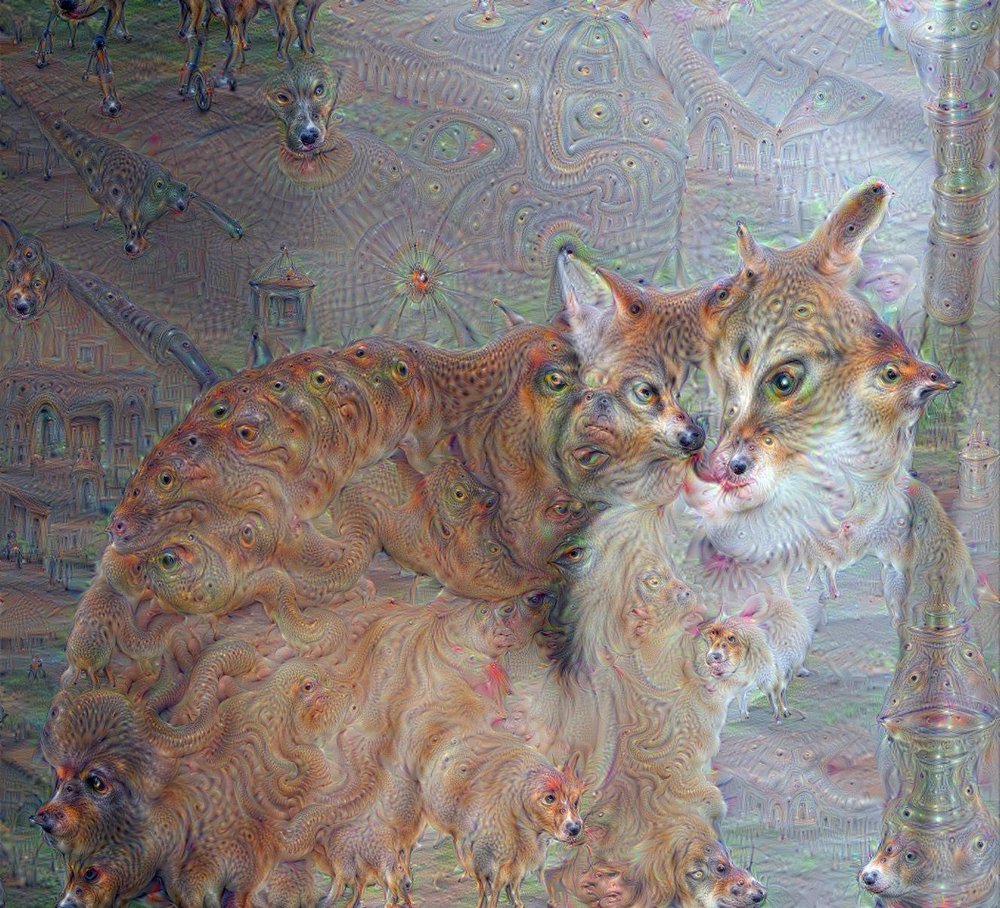

Beeple, Regular Animals, 2025. The installation itself is an attention engine — faces, movement, absurdity. A real-world embodiment of engineered attention.

Beeple’s Regular Animals at Art Basel Miami did not simply “go viral.” It engineered virality — a deliberate construction of Dogconomy™, where spectacle converts directly into liquidity and narrative.

This is not an artistic judgment. This is an analysis of how the attention economy behaves when someone understands its mechanics with extraordinary clarity.

Beeple reads contemporary culture with unusual precision. His Everydays practice operates at the same speed, compression, and hyper-reactivity that define our digital present. In many ways, Regular Animals is a testament to that fluency — a kind of virtuosity in attention architecture.

It is also important to say this clearly:

Beeple is not the benchmark for the average artist.

He enters the attention economy with a massive collector base, institutional visibility, and an audience ready to amplify anything he releases. Most artists do not step into the arena with this infrastructure — which is precisely why this activation becomes such a revealing study of how the system behaves at scale.

Anatomy of a Spectacle

Regular Animals made its logic unmistakable.

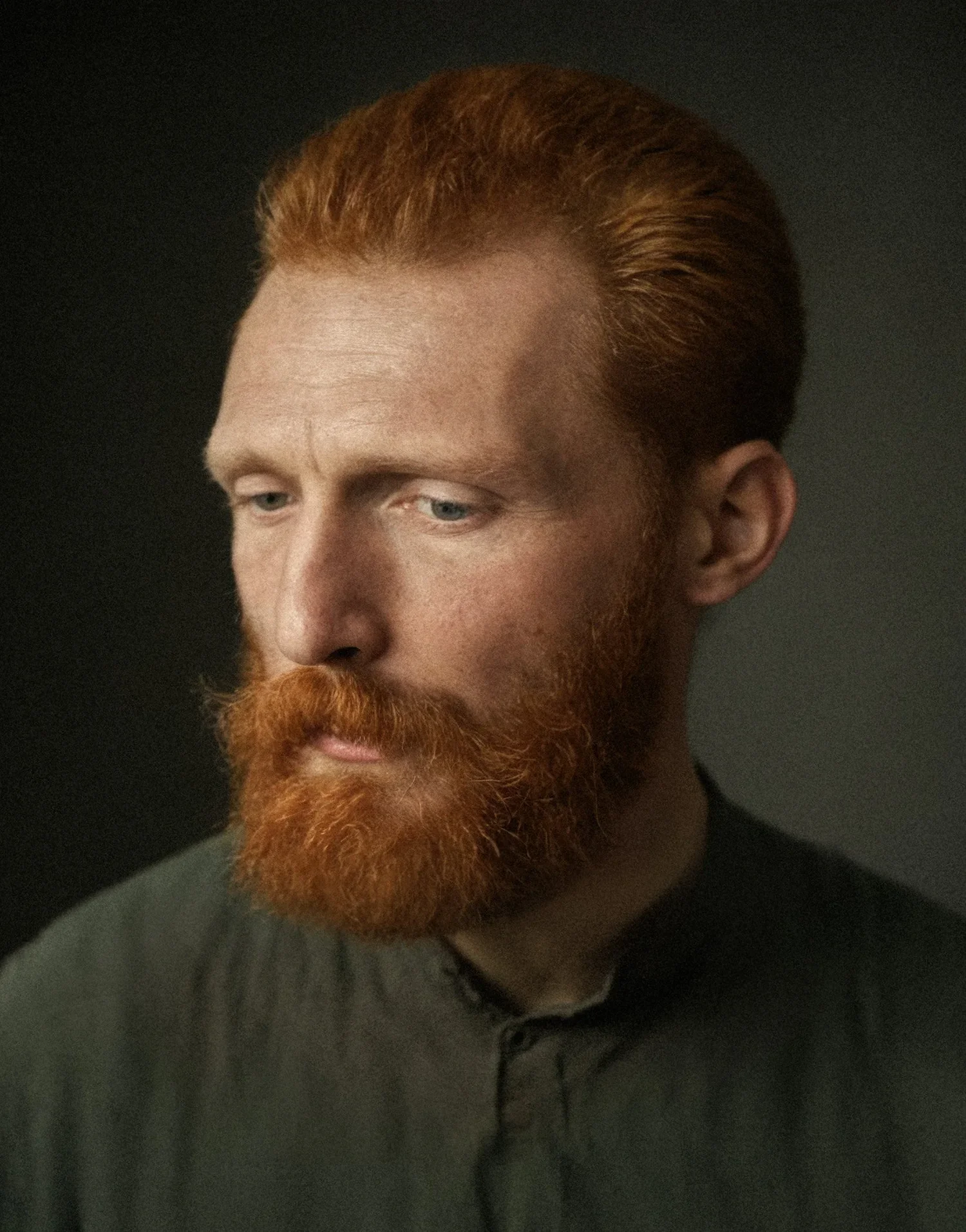

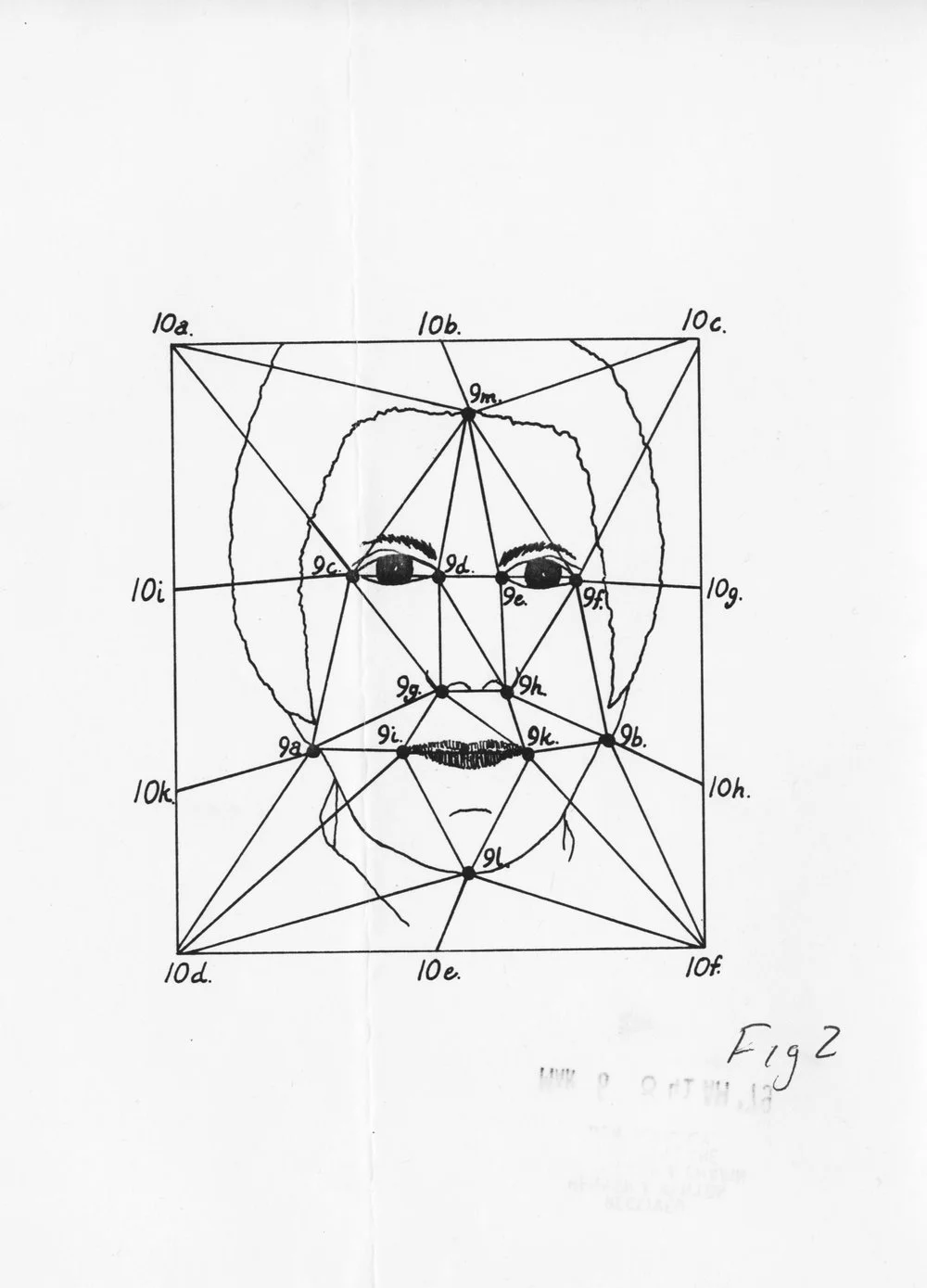

Robot dogs wearing the faces of Warhol, Picasso, Bezos, Musk, Zuckerberg — and Beeple himself — roamed the Zero10 corner, scanning visitors and ejecting prints. Using famous faces is not incidental: the brain’s face-recognition circuitry (fusiform area) activates automatically, making these images impossible to ignore. They trigger salience, authority cues, and instant recognition — all core levers of the attention economy.

By placing his own face among cultural icons, Beeple taps into a known cognitive bias: status association. When unfamiliar and familiar stimuli appear together, the mind unconsciously transfers value and importance across them. It’s not a conscious comparison — it’s automatic associative priming.

The installation stacked the strongest attention triggers at once:

· faces (biologically prioritized),

· movement (evolutionary threat detection),

· novelty/absurdity (pattern break),

· surprise (orienting reflex).

Together, these cues force a reaction before reflection — exactly how attention functions under cognitive load. In this sense, Beeple’s activation didn’t just live inside the attention economy; it demonstrated its mechanics with textbook precision.

This wasn’t designed for slow interpretation.

It was designed for capture — a spectacle operating at the level of instinct rather than intellect.

The “car crash you don’t want to see but slow down for anyway.”

And because Beeple already commands an enormous collector base, the loop accelerated far faster than it would for any emerging artist.

Scale amplifies show.

The Crowd as Engine

The work relied less on the object itself and more on the crowd who looked, filmed, and shared. Their phones and feeds became the distribution infrastructure — a live enactment of Metcalfe’s Law, where each participant increases the network’s power.

Most viewers formed judgments without context, a classic case of heuristic substitution: not “Do I understand this?” but “Is everyone reacting to it?”

The “free poop” prints tapped into casino psychology — randomness, intermittent reward, and anticipation. When a few began trading around 10 ETH, the loop accelerated:

price → posts → spectacle → more buyers → higher price???

But attention-driven pricing follows a well-documented cognitive curve: once the stimulus fades, salience drops, social proof dissolves, and buyers realize their decision was made under attention pressure rather than evaluation.

That’s when the loop reverses:

diminished attention → lower demand → falling price

Which is why many pieces purchased at the peak usually sit at a loss — a predictable outcome in attention markets where momentum, not conviction, drives entry.

A self-reinforcing circuit, until it isn’t.

To Beeple’s credit, none of this is accidental. He has shown up every day for years, building a base, mastering spectacle, and understanding exactly how attention behaves when pushed.

Few artists possess that combination of consistency, scale, and instinct.

So Who’s the Good Dog? — The One Who Gets the Most Attention.

Economically, this is value formed by salience rather than substance — where the artwork matters less than its visibility and the velocity of its circulation.

Beeple did not merely participate in the dynamics of attention. He demonstrated their mechanics with clinical clarity.

A real-time diagram of how contemporary culture — and Web3 markets — now work.

And from an attention-economy perspective, it was almost textbook-efficient.

The Burden (and Beauty) of Slowing Down of being conscious.

Jenny Holzer, Truism: Protect Me From What I Want, 1994. Predates Twitter/X yet operates exactly like a viral command — short, urgent, psychologically loaded. Image source: artsy.net

So What’s the Solution?

In a Culture Drowning in Noise and Starving for Thought**

We live inside a system where information multiplies faster than cognition can process it. Our attention is stolen before we even realize it’s gone. AI completes our sentences. Feeds complete our opinions. And our minds — overstimulated and under-rested — struggle to hold focus long enough to care about anything deeply.

So what do we do?

We slow down.

We reclaim friction.

We choose consciousness over reflex.

Every collector I interviewed in the Collecting Art Onchain book emphasized the same point:

Art needs time. Meaning needs oxygen. Reflection requires slowness.

Yet panic-driven purchases, group-influenced reactions, or emotionally charged “first come, first served” mint frenzies now sit at heavy losses.

Not because the art was weak — but because speed dictated attention. A classic heuristic shortcut: fast decision-making under perceived pressure.

And this is the real consequence of the attention economy:

We scroll. We skim. We react.

We rarely finish reading. We almost never think.

Critical thought requires friction. And friction has been meticulously taken out of our digital lives.

Our gaze moves wherever the crowd tilts — and somehow we still celebrate that as choice, as autonomy, as decentralization.

It’s almost funny, if it weren’t tragic. The “decentralized” mind moves in perfect synchronization with the algorithmic crowd, mistaking mass signals for personal conviction.

Recovering our attention — and our ability to think — isn’t a philosophical luxury. It’s the only way to participate in culture with agency rather than drift as audience.

Audit the Narrative - Ask the Hard Questions

Meaning is not found in the feed. Meaning is found in what the feed tries to distract us from.

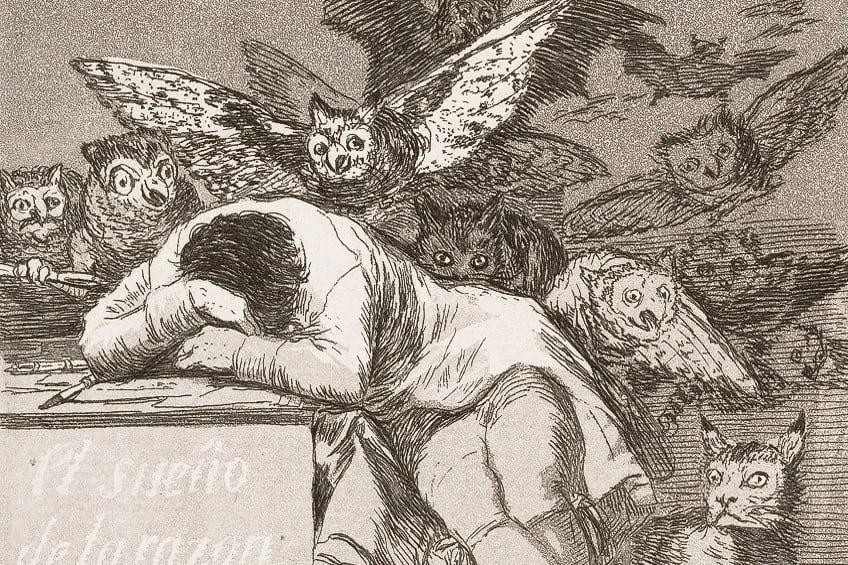

Francisco Goya, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, 1797-1799. Image source: artincontext.org

A moment of metacognition — a brief audit of our own habits before they quietly become our beliefs. Goya’s warning still applies: when awareness sleeps, other forces do the thinking for us.

If we want to reclaim our attention — and with it, our narrative — we have to practice a different discipline:

• read beyond the scroll

• think longer than we react

• look before we like

• disagree without exile

• reward depth over noise

• design systems that slow us down when the world accelerates

Meaning is almost never found in the feed. Meaning lives in everything the feed rushes us past.

In an economy built on attention, choosing where to look is the last form of freedom we fully control. And the future of digital art — of any culture worth preserving — depends on whether we exercise that freedom consciously.

xxx

★ Featured Artists/Artworks

René Magritte — The False Mirror (1928)

Pak — The Merge (2021)

Hito Steyerl — How Not to Be Seen (2013)

Nam June Paik — TV Buddha (1974)

Jenny Holzer — Truisms: Protect Me From What I Want (1994)

Francisco Goya — The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (1797–1799)

Beeple — Regular Animals (Art Basel Miami)

Curator Focus: Eleonora Brizi

Every movement has its chroniclers— those who don’t just witness change, but shape how it will be remembered. In Web3, we once imagined a world without tastemakers — a decentralized field free from gatekeepers, hierarchies, and inherited authority. “Let the code curate,” we said. But the truth is more human: the space still needs those who care — who can hold chaos long enough to find coherence, and who can translate technological acceleration into cultural continuity.

The Book On-Chain project introduces Curator Focus, an ongoing series of conversations with the individuals who build bridges between code and culture. Each edition highlights a curator who has shaped the evolving landscape of digital art — not as a gatekeeper, but as a custodian of context.

We open the series with Eleonora Brizi, one of the first to take curating on-chain seriously, long before institutions learned the language of tokens. Her role is as contradictory as it is essential: she curates but doesn’t collect; she builds platforms yet critiques their models; she documents rebels while refusing to be canonized. In a world that celebrates decentralization, Brizi insists that curation — when done with integrity and transparency — is not an act of control but of care.

Her work reminds us that in any system, decentralized or not, someone still decides what deserves attention — and how it’s remembered. The difference is whether that decision is made in service of ego or of ecosystem.

Eleonora Brizi

Eleonora Brizi is a curator, translator, and cultural mediator whose work sits at the intersection of dissent and historical memory. She entered the crypto art space as someone who had spent years embedded in systems where the stakes of expression were life-defining. Her journey began in Beijing, where she worked for four years inside the studio of Ai Weiwei, at a time when surveillance was constant, exhibitions could be shut down overnight, and the simple act of artistic collaboration could carry political risk. It was there, surrounded by dissident artists and young Chinese staff navigating real consequences, that Eleonora developed the instincts that would shape her later work in crypto art.

When Eleonora arrived in the crypto space in 2018, she recognized something familiar: not the aesthetic, but the energy. Within weeks, she began archiving the Rare Pepe phenomenon, then widely dismissed, and co-created The Rarest Book, one of the first serious curatorial efforts to historicize early blockchain art through a cultural lens. Since then, her work has remained unusually grounded in geopolitics, cultural translation, and real-world access. She curated Renaissance 2.0 2.0. in Rome during the pandemic, building an exhibition of digital-native art inside a traditional space with no funding, little precedent, and minimal institutional support, yet drawing hundreds on opening night. She has spent the last few years traveling between Europe and China, where she is now developing a blockchain-specific Chinese vocabulary and working to understand how regulatory, linguistic, and infrastructural barriers shape who can participate in Web3.

Unlike many in the space, she doesn’t believe in artificial scarcity. She believes in access. She speaks the language of context, of curation, of culture. Her influence in crypto art is hard to quantify precisely because it isn’t extractive. It’s archival and found in the bridges she builds between artists and institutions, between East and West, and between a decentralized promise and its all-too-centralized reality.

Freedom as a Medium

When Eleonora Brizi first encountered crypto art, she wasn’t looking for blockchain. She wasn’t even looking for art. “I didn’t study art,” she says. “I studied Chinese and Chinese culture. But I was interested in art as a way to understand dissent.” That interest took her deep into China’s underground. Her university thesis focused on The Stars Art Group, a radical collective of artists in post-Mao Beijing who staged unsanctioned exhibitions in the streets. One of them was Wang Keping, the exiled sculptor who handed her a handwritten letter of introduction. “He told me, ‘You should go to Ai Weiwei. Would you like to work for him?’ I said, ‘Of course.’ And he wrote a letter. He told me, ‘Don’t call, don’t email, it’s complicated. Just go to Beijing, go to the studio, and hand him this letter.’”

So she did. Fresh out of school, with no job and no plan, Eleonora flew to Beijing and walked into Ai Weiwei’s studio. “He looked at it and said, ‘This is from one of my best friends. He’s my brother. We can try for three months.’ I stayed for four years.”

Image of the Stars Art Group. Source: royalacademy.org.uk

Those four years shaped her. “It was my first job,” she recalls. To her, the experience was like breathing freedom of expression every day. The studio was under constant surveillance. “The Chinese people who worked there were incredibly brave,” she said. “They were risking something real. For the foreigners, we were safe. But for them, it meant surveillance. It meant trouble.”

“It was my first job, and I developed my work experience in a place where I was breathing freedom of expression and freedom of speech every day.”

When Ai Weiwei finally left China for Berlin, Eleonora stayed. She worked for other artists and spent two more years immersed in China’s complex cultural landscape. But in 2018, she needed change. “I had this thought: after all this time in China, I don’t know anything about the U.S. I wanted to see what was happening.” Two weeks after arriving in New York, she attended a blockchain conference at the National Arts Club in Manhattan, where she met speakers such as SuperRare John, Judy Mam from Dada, Jessica Angel, and members of the Rare Pepe project. The Rare Pepe project, in particular, caught her attention and made her realize that curatorial work could give context and meaning to this new, emerging space.

After the conference, at a dinner, she asked, “Do you have any literature on this? Something we could bring to the art world and say, do you know this exists?” The founders hesitated. “They didn’t want curators. They didn’t want paper. They didn’t want anything. But someone smart enough said, ‘We can do a book.’” So they did.

The Rarest Book, 2018 by Eleonora Brizi. Source: wiki.pepe.wtf

That October, she launched The Rarest Book, a curatorial publication about Rare Pepes, first at the New Art Academy conference, then again the next day at Bushwick Generator. “All the New York community actually came,” she says. “That’s how I started. And that’s how I think I transitioned from Ai Weiwei to crypto art, because I found the same need and like screaming for freedom of expression… It was always with the rebels. And it was always with the socially involved art somehow, like social change. Either from like a dissident or crypto art, which is a way to be dissident, you know, that’s, I think, what always drew me.”

Renaissance 2.0 2.0: The Child of Its Own Time

In 2020, as the world braced for lockdown and Italy became the first European country to shutter its cities, Eleonora Brizi was preparing to launch one of the earliest in-person exhibitions dedicated to blockchain-based art. She called it Renaissance 2.0 2.0., a nod to the idea that this moment wasn’t a continuation of the Renaissance, but a reformatting of what “art” might mean altogether. The venue was unexpected: a historic gallery in the heart of Rome. “I found a man,” she says, laughing softly. “He was the owner of this amazing space in Rome, and he knew nothing about digital art. Nothing about blockchain. Nothing about what I was doing.”

But maybe that was the point. “He said to me, ‘I’m so bored of doing religious exhibitions. Of always showing the Renaissance, or just rehashing history. I want to do something different.’” When he asked her how much money she had, her answer was blunt: “Zero. I have zero. But I’m not a thief,” she added, “so if I need to get sponsors, I can try.”

Opening of the Renaissance 2.0 2.0 exhibition in 2018 in Rome, curated by Eleonora Brizi. Source: movemagazine.it

Instead of turning her away, he said yes. “I’ll give you the space for free,” he told her, “but promise me one thing, we make a printed catalog.” He ran a publishing company and liked the idea of anchoring the ephemeral into something tangible. “That’s why we have the Renaissance 2.0 2.0. catalog,” she explains. “It’s because of that agreement.” The show was meant to open in April 2020. Then came the first lockdown. The date was pushed to June, and that was still not possible. Eventually, it landed in October. “We called it the miracle show,” Eleonora says. “Because everything was working against us. COVID, logistics, travel, timing, my own health.”

“I was sick, in pain, completely overwhelmed. I had no assistant. I was doing everything alone.” But what made Renaissance 2.0 2.0. even more extraordinary was the fact that no one in Italy knew what crypto art was. “Nobody knew,” she says flatly. “In New York, it was small but growing. But in Italy? Nothing.” Still, she persisted. “Because I believed in the art. I believed in the artists.”

But then came more restrictions. “Every Monday, the government would issue new rules. First, they took away the cocktail from the opening. Then they took away the conference I had planned, panels on blockchain and art, with people flying in to speak. Gone. Then more rules: no gatherings in enclosed spaces. No mingling. No drinks. No nothing.”

And then, another blow. The artists, many of whom had planned to install their own work, backed out. Some had virtual sculptures. Others needed to be on-site to adjust digital equipment, test VR displays, manage installations. “But nobody came,” she says. They were scared. Or flights were cancelled. Or they just couldn’t risk it. So there she was: a single woman, surrounded by screens and cables and boxes of artwork, trying to pull together a show with no support, no event, no clear audience.

“Even without a cocktail, without music, without a conference... 550 people came. Five hundred and fifty people, in Rome, showed up just to see the art.”

The owner of the space came to her and asked: Do you want to postpone? Eleonora thought about it. And then, in her words: “I said, this show is the figlio, the child, of its own time. It was born of COVID. It carries that energy. We go ahead.” And then something extraordinary happened. “Even without a cocktail, without music, without a conference… 550 people came. Five hundred and fifty people, in Rome, showed up just to see the art. With masks, of course.

Hackatao’s work at the Renaissance 2.0 2.0 exhibition in 2020 in Rome, curated by Eleonora Brizi. Source: movemagazine.it

“That’s when I knew,” Eleonora says. The work mattered. People wanted to see something different. They didn’t come because they understood crypto. They came because they were thirsty. And yet, in the eyes of the art world, the show barely registered. She had no institution backing her. No collector press. No critic from Frieze or Flash Art writing it up. But for those who attended, Renaissance 2.0 2.0. was a vision of digital art in situ, in space, surrounded by the silence of a culture in shock. And for Eleonora, it marked a turning point in how she had to present herself.

In 2019, there was no such thing as a crypto art curator. The role didn’t exist. So she adapted. “I needed language that people could understand. So I said I had a gallery. A gallery of art and technology. That’s how I presented myself. Nobody would have understood if I said I was curating decentralized, token-based, digital-native work. But everyone understands ‘gallery owner.’” And yet, the irony lingered. She was curating work born of decentralization, of borderlessness, frictionlessness, and radical access. But the world she had to translate it into still ran on old expectations, old language, and old hierarchies. Even the crypto art world, for all its claims to openness, wasn’t immune.

Beyond the Western Node

For a space that claims to be decentralized, the crypto art world is strikingly narrow in its geography. “Europe and the U.S.,” Eleonora says. “And now, a little bit, the Middle East. But where are the artists?” By artists, she doesn’t mean the handful of non-Western names dropped into curatorial press releases to meet diversity quotas. She means creators, platforms, collectors. Entire ecosystems that remain untouched because the infrastructure we build is rarely designed to include them. “All these artists we’ve supported until now,” she continues, “are probably, I don’t know if you can say 90%, maybe even 95%, American or European.”

It’s not that she wants token diversity. In fact, she’s deeply skeptical of the “one-from-everywhere” model that tokenizes inclusion while leaving its structural problems intact. “I don’t like to force things,” she says. “I don’t like politically correct submissions where you need one person from here, one from there, one of this gender. I understand why we do it, but it’s been pushed too much.” For Eleonora, inclusion should be driven by genuine cultural curiosity. “We should genuinely be interested in different cultures. We should onboard them not because we need to appear diverse, but because it’s interesting. China is completely different.”

In 2025, she visited China again, her first time back in years, and was stunned by what she found. “I was shocked,” she says. “The technological possibilities, the availability of devices, the quality of the infrastructure, it’s another level.” Reflecting on the contrast, she adds, “We’re still using TVs, while they have entire circular rooms with huge wraparound screens. The sound is spatial, coming from every direction. The technology is outstanding — the installations are beautiful, the spaces are impressive.” She recalls visiting UCCA and Deji Art Museum in Nanjing. “There’s still a lot to integrate—different systems, different cultural approaches—but it’s not about who’s better or worse. It’s just different. It would be wonderful if we could find ways to connect these worlds and exchange knowledge and access between them.”

“…it’s not about who’s better or worse. It’s just different. It would be wonderful if we could find ways to connect these worlds and exchange knowledge and access between them.”

And yet, despite the resources, China remains absent from Web3-native conversations. Not because of disinterest, but because of barriers, legal, political, linguistic, and financial. “These barriers are very real,” Eleonora says. “But there are ways around them. Not illegal ways, just different pathways.” She points out that digital art is already present and widely visible in mainland China, yet conversations around NFTs or crypto often remain muted. “The art is in mainland China, for all the Chinese public to see. But nobody’s talking about NFTs or crypto,” she explains. “The wallets, however, are based in Hong Kong, where the transactions are carried out legally.”

This, she suggests, might be the way forward: not trying to make China conform to Western models of crypto adoption, but understanding how parallel systems operate within constraint. “Maybe you don’t say, ‘Hey, we’re paying in crypto.’ Maybe you find another entry point. A legal structure. A payment solution. A gallery partner. Maybe that’s not ideal, but it’s better than pretending entire regions don’t exist.”

Building for the Future

For Eleonora, the limitations of Web3 art aren’t only geographical — they’re generational. The same structures that exclude new regions also fail to reach new audiences. ”We’re not talking to the new generation,” she says bluntly. “The collectors we keep begging to come into the space? They’re not young. They’re not the future.” This hits a nerve. Because for all its rhetoric about change, the crypto art world has increasingly sought validation not from new systems, but from old institutions.

“We still think approval has to come from Christie’s,” she says. “That’s what everyone still believes. And I’m so disappointed. I promise you, not many people are building for the next 20 years.” The focus on prestige has created what she calls a “confused space,” a community speaking in new language while still chasing old approval. “We want the old institutions to recognize us. But we’re not speaking to the young people who will actually stay. And we’re not making it easy for them.” Her critique is unsparing. “These wallets? This UX/UI? It’s incomprehensible. We think it’s user-friendly because we already know how it works. But go talk to someone new, even someone young but outside crypto, and they’re completely lost.”

The solution, she believes, is fundamental rethinking. “We need to speak a new language. Not just about the future, but for the future. And that means talking to people who aren’t crypto bros, who aren’t whales, who don’t care about institutions but care about art.” For Eleonora, the tragedy isn’t that these people aren’t here. It’s that they were here, and left. Or were never invited. Or didn’t understand the rules.

“I’m disappointed in how we consigned these artists,” she says. “The ones we helped build from the beginning. And now their biggest chance to make history is to be validated by institutions that never cared.” She pauses. “Why didn’t we build our own institutions?” She’s not just asking rhetorically. She’s asking as someone who helped build the space from the ground up, someone who curated when “curator of crypto art” wasn’t even a job title, who co-authored The Rarest Book, who gave Pepe culture its first formal historical framing, and who still finds herself watching the same story repeat: artists chasing institutional approval from the very world they tried to disrupt. “Sotheby’s and Christie’s?” she says. “The level is too low for me.” It’s a rare thing to hear someone say out loud in the crypto art space, where prestige still exerts a gravitational pull. But for Eleonora, the auction houses represent everything that went wrong. “I’m so disappointed,” she says, quietly. “You don’t even know. I’m so disappointed in how we consigned these artists to the same old systems. And now their biggest chance is to be validated by institutions that never cared.”

The salesroom at Sotheby's during the"Grails" sale, dedicated to digital artwork owned by Three Arrows Capital. Source: Sotheby's

“These artists even brought their own collectors to them,” she says. “They didn’t do anything for the space. Literally nothing.” Her anger is palpable, but it’s the kind that comes from care. “We helped build these artists,” she says. “We built them from zero. And now their biggest opportunity is to be consigned to the Whitney, or MoMA. And we all act like that’s a victory.” But then she asks the question that undoes the whole framework: “Do we have an alternative?”

Because maybe, she says, that’s the problem. We never finished building the house. We started something radical, a new model, a new medium, a new value system, but when the flood came, we ran back to the old institutions for shelter. “What does an alternative even mean?” she asks. “It doesn’t mean building a museum of crypto art. People already tried that. That’s not the answer. The question is: if this art is digital, and as you said, dynamic, how do we build something for that?”

“The question is: if this art is digital, and dynamic, how do we build something for that?”

She’s not convinced anyone is asking the question seriously. “All the platforms that were built? They’re dropping one by one. They don’t work. Why? Because it’s an old model. Backed by investors. Not really decentralized. Not really new. Just a replication of the same gallery logic, but digital.”

“We never built the alternative,” Eleonora says. “We didn’t build it because we didn’t talk about it. We didn’t gather around the question. We just built faster versions of the same machine.” But the old machine doesn’t work for this art. That’s her point. Digital art isn’t slow, isn’t static, isn’t built for archives and temperature-controlled rooms. “If the nature of the art is dynamic,” she asks, “how are we going to respond to that?” She doesn’t claim to have the answer. But she insists we have to start the conversation. “This is what we should be doing. Not just more drops. More hype. More Twitter threads.”

Her own relationship to collecting complicates the narrative even further. She’s not a collector. Not even casually. “I’m a little weird about collecting,” she says. “I don’t collect anything, really. I’m not attached. I don’t feel the need to own.” Even when she loves a work, champions it, curates it into visibility, she doesn’t feel compelled to keep it. “I push hard for people to collect when I believe something should be collected. But me? I don’t need to own it. I don’t even do that with objects. If someone gives me something, I’m happy, but I don’t attach.” If she had more money, she says, it would be different, but not in the way you’d expect. “I’d be a patron,” she says. “Not a collector. I’d support. I’d help artists financially, if I could. But not to accumulate. Just to make sure they’re okay.”

This detachment from possession is a way of keeping the focus on the art, and the ecosystem around it, rather than the objects it produces. “It’s a little crazy, right?” she laughs. “I’m the co-founder of 100 Collectors, but I’m more interested in helping others collect. I just want this art to be supported.” The irony is sharp, but not surprising. In crypto art, as in traditional art, many of the most influential figures don’t appear on collectors’ leaderboards. They don’t make headlines. They don’t throw millions around. They build the rooms. They hold the archives. They do the memory work.

The Unseen Builders

Web3’s foundation wasn’t built by institutions, but by individuals, many of them women. “It’s absolutely not true that there aren’t women at the foundation of this space,” Eleonora says. “Look at Dada. Judy and Beatriz. One of the most innovative experiments in crypto art, two women.” She names others: “Serena Tabacchi started curating early. Kate Vass Galerie was one of the first. When I curated the Pepe book in 2018, there were no other women doing that. No other curators.”

But still, the visibility remains low. Especially on the collector side. “Yes, women are here,” she says. “We’re founders. Builders. Curators. But not whales.” And when women do collect, they’re often hidden behind male aliases, male faces, male wallet names. “Fanny Lakoubay often mentions this,” Eleonora says. “There are women behind many male collectors. They collect as couples. They make joint decisions. But the man is the one who gets remembered.” Even in the simple act of extending an invitation, this is visible. “Fanny is always careful,” she says. “When we invite someone for dinner, we include the wife, because she is behind it. She’s collecting. She’s shaping the decisions. She just doesn’t get seen.”

“Yes, women are here. We’re founders. Builders. Curators. But not whales.”

The reasons for this imbalance, Eleonora explains, are complex. “It’s all connected — finances, family, time,” she says. “And it’s not only in crypto art, it also happens in the traditional art world, but it’s especially visible in our space.” At the beginning, most of the first collectors who shaped the taste of early crypto art came from the crypto world itself. “For example, there’s Kelly leValley,” she notes. “She’s an amazing Bitcoiner and investor. She’s very successful, a serious collector, and someone I would consider a rare example of a financially independent woman in this space. She invests in Web3 companies, she collects, and she’s completely independent. She got into Bitcoin at the right time.” But such examples remain rare. “That world, the world of funds, exchanges, trading, it’s still very male. Maybe because it’s built on competition, risk, speed, things that were never made to include women,” she says. “You probably need a lot of testosterone for that.”

The imbalance, she suggests, isn’t just cultural; it’s structural. “Until recently, there weren’t many possibilities for women to become financially independent,” Eleonora says. “That’s why we also have fewer female artists. Many didn’t study art, or weren’t allowed to.”

Change, however, is happening — slowly but visibly. “It’s improving,” she says, “but we need more time. It’s not one single issue. It’s everything together — history, money, education, opportunity. But it’s shifting.”

The team of 100 Collectors: Eleonora Brizi, Fanny Lakoubay, and Pauline Foessel. Source: Eleonora Brizi

The Language of Defiance

Eleonora Brizi doesn’t speak the language of hype. She speaks the language of art history, of defiance, of cultural memory. And when she stepped into the world of crypto art, she didn’t bring investor logic or VC bravado, she brought something rarer: curatorial integrity.

“When you work with someone like Ai Weiwei,” she says, “you learn what it means to make art that stands up to power.” It also taught her how institutions can fail. As she documented Ai’s work and began building bridges between contemporary Chinese artists and European audiences, Brizi quickly saw how slow and risk-averse traditional art institutions could be. "I was always trying to translate between two worlds,” she explains, “and too often, I saw how Western institutions didn't know how to read what they were being shown.”

So when she discovered the Rare Pepe project, something clicked. “It was crude, irreverent, unfiltered. But it reminded me of China. Of resistance. Of art that wasn’t waiting to be approved.” From that point on, Brizi became one of the first women in the crypto space to approach NFTs not as a financial instrument, but as an emergent language of cultural and political significance. She began researching the history of Rare Pepes obsessively, curating not just with an eye for value, but with a commitment to context. “I understood that if we didn’t write this history down, it would be erased,” she says.

Brizi has since curated exhibitions across Lisbon, Milan, and Paris, but she’s remained critical of how Web3 has begun to replicate the same institutional power structures it once aimed to replace. “We talk about decentralization,” she says, “but so many artists still struggle to stay in the space and truly benefit from the ecosystem. There’s no real infrastructure of care.” She sees collecting not just as an act of acquisition, but of memory. A collector is also a recorder. A curator of future knowledge. And she’s quick to challenge the notion that market value should define which artworks survive.

It’s why she remains suspicious of crypto art’s obsession with scarcity as a proxy for value. “Scarcity belongs to the old economic system,” she says. “The digital was never meant to replicate it — it should be abundant, not scarce.”

In a space still dominated by male collectors and loud capital, Brizi’s presence is quiet but seismic. She connects, she teaches, she preserves, and she makes space for others to be seen.

236.4 Million Reasons to Worry

Kate Vass examines Gustav Klimt’s record-breaking $236.4 million sale at Sotheby’s, arguing that such events signal market anxiety rather than confidence. The essay contrasts the traditional art world’s obsession with rarity and spectacle with Web3’s original promise of transparency, shared authorship, and cultural preservation.

236.4 Million

“When the art world applauds a $236 million sale,

it isn’t celebrating art. It’s celebrating the survival of its own mythology.”

$236 million. What if a record sale isn’t a triumph — but a warning?

Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer just sold for $236.4 million Sotheby's — the second-highest price ever paid for an artwork, celebrated as proof that the market is “back.”

But record sales rarely signal confidence. They signal fear.

They’re not about art — they’re about reassurance.

Lets look into how value transforms into myth — and how both traditional markets and Web3 mirror the systems they were meant to transcend.

236.4 Million is what Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer fetched at Sotheby’s.

To many, surprisingly, it’s was considered as a signal for the 'bull market' or that the market is back; when, as a matter of fact, it’s a signal that something deeper is shifting.

History tells a different story: big numbers rarely announce stability — they betray anxiety. When prices soar, they don’t always rise on confidence; they rise on the need for reassurance.

In September 2008, Damien Hirst’s Beautiful Inside My Head Forever sale at Sotheby’s totaled £111 million — the same week Lehman Brothers collapsed. Within a year, global art sales had fallen nearly 40%.

Big numbers move through markets with purpose — converting visibility into legitimacy, power into permanence, capital into myth. Whether motivated by estate strategy, geopolitical prestige, or tax choreography, such transactions say less about the vitality of art than about the condition of the world that buys it.

Yes, Klimt’s portrait is an extraordinary work — luminous, psychologically charged, and steeped in history. Yet the sale wasn’t about art. It was about assurance.

A single transaction between a seller repositioning assets and a buyer consolidating cultural capital — staged, amplified, and consumed as proof that the old order remains intact. Since the painting was sold by Ronald S. Lauder’s estate following his death in 2025.

High-value auctions have little to do with cultural health and everything to do with market choreography: year-end tax strategies, intergenerational wealth transfers, and discreet asset swaps.

The numbers are designed not to inform but to mesmerize. So while the recent sale may read as market exuberance, it’s better understood as a ritual of reassurance.

One transaction mediated by a centuries-old system of opacity, not liquidity — a trade that celebrates closure: the artist long gone, the market mature, the work canonized.

The louder the applause in the auction room, the quieter the confidence outside it.

Markets as Mirrors

Every market designs the world in its own image.

The traditional art market is singular — one masterpiece, one buyer, one myth.

It thrives on scarcity, opacity and spectacle.

The blockchain economy, when true to itself, is plural — editions, forks, shared authorship.

It thrives on transparency and participation.

When the Web3 community celebrates a record sale in the legacy art world as its own victory, it confuses the mirror for the window. What it sees is not progress but reflection — the echo of an older system masquerading as relevance.

Decade ago, decentralization offered a way out: a framework where art could be verified, preserved, and shared without hierarchy — without the old gatekeepers of value and taste.

But systems regress when they forget why they exist.

The market doesn’t just trade art; it teaches us what to desire, how to measure meaning, and when to declare victory.

The question is: whose logic are we still serving?

The Misunderstanding of Metrics

Within hours, Web3 timelines lit up.

Screenshots of the Klimt sale circulated with captions like “New ATH for art!” etc.— as if one record price in the legacy market were proof of crypto’s revival.

The irony is hard to miss.

A community founded to challenge opacity and financial elitism now celebrates the same metrics of speculation. ATHs, floors, blue chips — the lexicon of liquidity has replaced the language of meaning.

This confusion exposes a deeper anxiety: the need for validation from the very systems we claimed to disrupt initally.

Web3 doesn’t need another benchmark sale; it needs a benchmark in values.

Its purpose was never to out-price the old world but to out-context it — to build a network of provenance, authorship, and care that doesn’t depend on fiat applause.

Klimt’s record is a ritual of closure.

Web3 should be a ritual of opening.

The Economics of Mythology

Record sales rarely emerge from moments of creative expansion; they surface in times of contraction — when capital seeks shelter in symbols. These events don’t signal growth but defense: markets protecting themselves under the guise of triumph. High-end auctions often align with fiscal deadlines, estate settlements, or discreet wealth transfers. Art becomes a soft landing for capital — a gesture of permanence in an age of volatility. The traditional art market builds value through narrative accumulation — curators, scholars, institutions, and time. Each layer fortifies the myth until value feels inevitable.

Web3, by contrast, still swings between speculation and amnesia — where noise replaces narrative, and liquidity pretends to be legacy. If we want cultural permanence, we must create it — not by mimicking a fading system, but by building new architectures of preservation and creativity — the very ones we were meant to establish years ago. Art on-chain will only gain historical gravity when its metadata, provenance, and meaning are protected with the same care Sotheby’s grants its clients’ anonymity. A single record sale may validate the past. But systems — not prices — sustain the future. Because myth alone cannot preserve culture. Only validated context can. So when Web3 celebrates a legacy auction as a “bull signal,” it reveals a deeper insecurity: the belief that legitimacy can still be bought.

So when Web3 celebrates a legacy auction as a “bull signal,” it reveals a deeper insecurity: the belief that legitimacy can still be bought.

Here are some key factors about the artwork sold👇

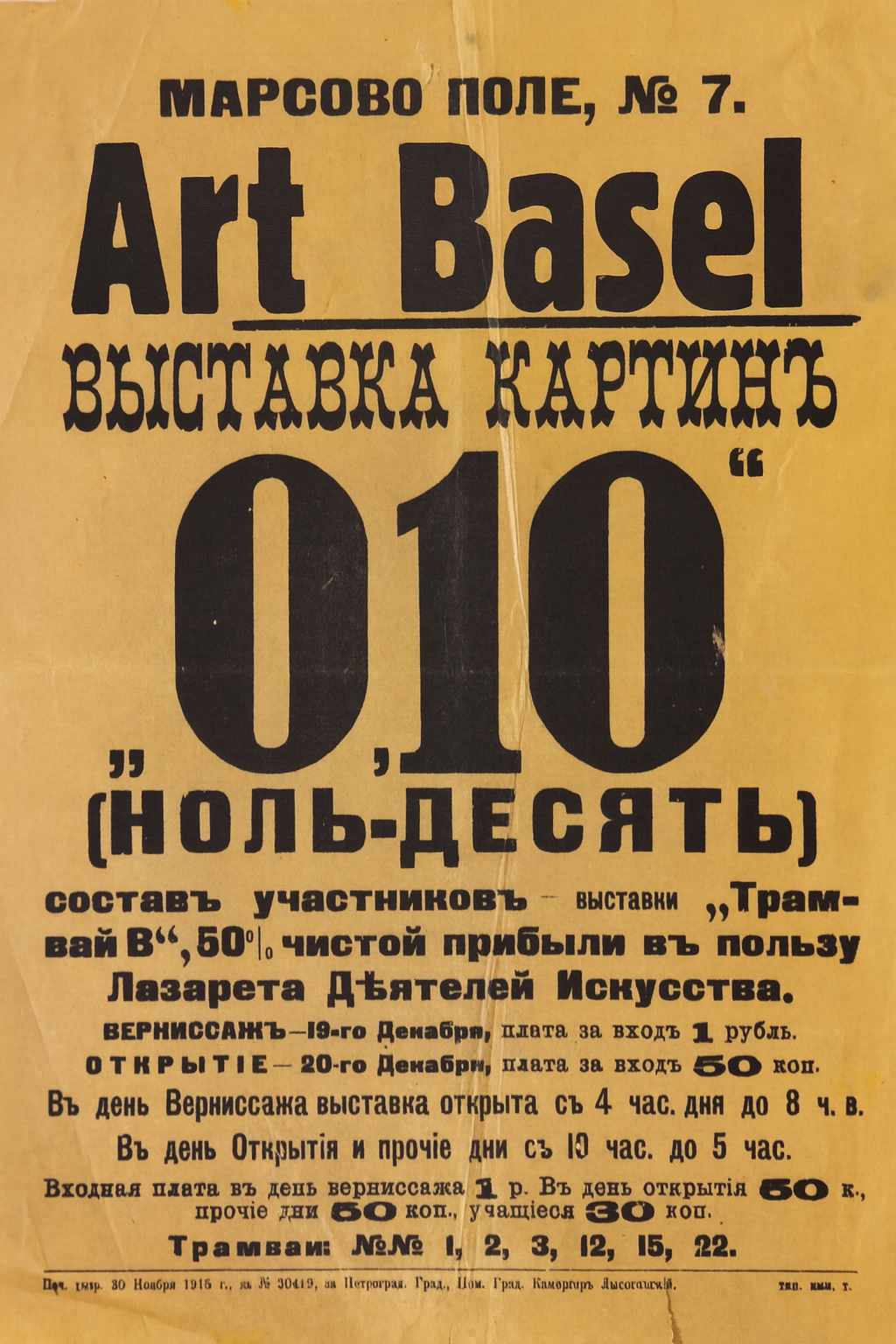

The Future Has No Walls

The Future Has No Walls explores how Art Basel Miami’s new Zero10 “digital-first studio” marks a symbolic shift in the art world, challenging long-standing gatekeeping systems while revealing deep contradictions in how institutions approach digital culture. Borrowing its name from Malevich’s radical 1915 exhibition 0,10, the initiative claims innovation but risks reducing Web3 to a marketing gesture inside the very walls it was built to dismantle.