A Mathematical Visual Poem: A Cognitive View of "Pandemic Meditation" by Kaz Maslanka

Kate Vass Galerie is excited to feature an article written by Kaz Maslanka about mathematical visual poetry. Maslanka, an aerospace engineer, artist, mathematical visual poet, and philosopher, has been a pioneer of this genre since the early 1980s. In his article, Maslanka introduces the concept of mathematical visual poetry through one of his recent works, "Pandemic Meditation," and focuses on a particular structure known as the Similar Triangles Poem or Proportional Poem. The article (A Cognitive View of "Pandemic Meditation" (A Mathematical Visual Poem)) was originally published in the January 2022 issue of the Journal of Humanistic Mathematics.

Mathematical visual poetry is a poetic genre whereby metaphorical expressions are created using mathematical structures. Within the structure, the poetics are understood by the cross-mapping of numerous conceptual domains including visual, lexical, and mathematical. Here I focus on one particular mathematical visual poetic structure: what I call a Similar Triangles Poem or Proportional Poem. To illustrate the ideas discussed, I present “Pandemic Meditation,” a mathematical visual poem; in particular, I discuss how this mathematical poem uses the mechanisms of poetic metaphor in the context of the embodied mind. The intent of this paper is not to explain “Pandemic Meditation,” for explanations of poetry serve only to kill it. Instead, the intent here is to give the reader the tools to access similar triangles poems in general, and this expression in particular, and to show how it functions within the definitions of poetic metaphor. This paper can be used as a template to study all similar triangles visual poems, and more generally, as a source to study visual poetry.

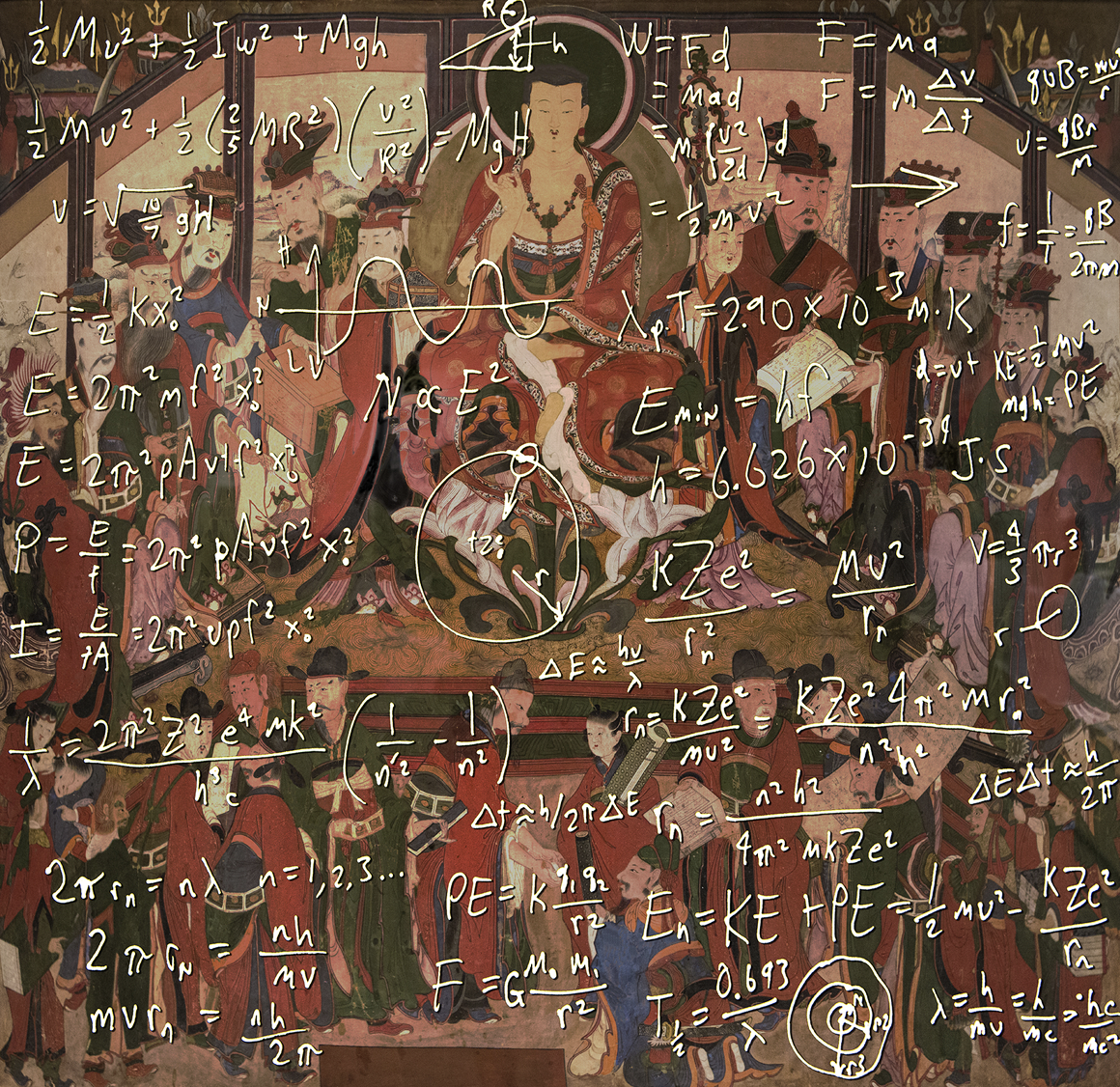

1. Inspiration For “Pandemic Meditation”

Figure 1: Physics equations and a Korean painting of Myeongbujeon (Hell). Illustration only. By Kazmier Maslanka: photo of art work overlayed with equations.

The imagery in Figure 1 comes from a photo I shot at the Philadelphia art museum and is a Josen Dynasty (Korean) painting of Myeongbujeon (Judgement Hall), where the ten kings of Hell reside to judge the dead. Overlayed across the painting, I have chosen to display equations from physics.

The great zen master Hyon Gak Sunim repeatedly states that zen meditation is a “technology” delivering one to understand their “true self”. The enlightened state of meditation happens before thought, so the barrier to enlightenment is the act of thinking. It is interesting to note that Rodin’s sculpture “The Thinker” sits at the gates of hell. In what follows, I share with the reader a particular outcome of the overwhelming act of thinking inspired by the real-time horrors during the pandemic of 2020.

I have always had an affinity for Eastern wisdom, and I have been fortunate enough to have been introduced to a few Korean Seon (Zen) masters. It is their insight that continues to help me with my continuing endeavor to learn more about and live my life guided by their wisdom. As part of this endeavor, I continue to practice meditation, which through much effort has kept me sane during the pandemic.

More specifically, meditation keeps me grounded in the present moment. When one is in the present moment, one can detach from the discontentment that is inherent within the human condition. In these recent days of the COVID-19 pandemic, I have not achieved this state easily, to say the least. The chaos surrounding the affliction has made meditation challenging. The stress of watching the bodies in New York City being stored in refrigerated trucks on the streets due to there being nowhere else to put them has been extremely disturbing for me. The endless news cycles constantly remind me of my age as well as the volatile populations that remain at risk. The latter, among other issues during this crisis, have kept me up at night thinking about family.

The poetic expression, “Pandemic Meditation” (see Figure 2), was inspired during an anxiety-ridden meditation I experienced. Observing my mind was a trial, as the ideas and visual elements seemed to jump about incessantly. During this particular meditation session, thirteen anxieties were spinning around my mind—empty—yet, I was attached such that I could count them. It was a dark space and this is not particularly how I’d like to report meditation. Meditation is the most successful way to minimize anxiety and it helps provide inspiration to continue my poetic expressions. And in this instance, it provided me with an experience where I could see relationships in a way as to point me in the direction of where more practice is needed. I collected my thoughts, arranged, ordered them, and created this expression.

2. Cognitive Linguistics

Figure 2: “Pandemic Meditation,” digital mathematical visual poem, 2020. © Kaz Maslanka.

I want to discuss the mechanisms of poetic metaphor, but before I can do this, f irst we need an understanding of basic or conventional metaphor. Conventional metaphor is the type of metaphor we use in our normal conversations and must be understood in order to study literary metaphor. A comprehensive study of metaphor is beyond the scope of this paper. However, I would like to put forth some initial concepts and definitions concerning metaphor.

A conceptual domain is any construction of coherent thoughts that can be understood in reference to our experience. While limited, for expediency, you may want to start off by just thinking of a conceptual domain as a mental construction, idea, or concept. Lakoff states:

“Each such conceptual metaphor has the same structure. Each is a unidirectional mapping from entities in one conceptual domain to corresponding entities in another conceptual domain. As such conceptual metaphors are part of our system of thought. Their primary function is for us to reason about relatively abstract domains using the inferential structure of relatively concrete domains.” [4]

When constructing or analyzing a metaphor, we perform an ontological mapping across the source domain to the target domain. That is, we understand all the elements of the target domain in terms of what we know about all the elements of the source domain. The source domain expresses concrete concepts where the target domain expresses relatively abstract concepts.

To better understand these mappings between the source and target domains, we need a nomenclature to discuss them. Cognitive linguists name the metaphors using the mnemonic, TARGET IS SOURCE. To illuminate how the nomenclature works for analyzing conventional conceptual metaphor, Lakoff describes the process as:

“Aspects of one concept, the target, are understood in terms of non-metaphoric aspects of another concept, the source. A metaphor with the name A IS B is a mapping of part of the structure of our knowledge of source domain B onto target domain A.” [5]

Lakoff gives us the example LOVE IS A JOURNEY. In this metaphor, we understand the ontology of love in reference to the ontology of a journey. In conventional metaphor, a metaphorical expression is the language used to convey a metaphor. It is important to note that a metaphorical expression is not a metaphor. The metaphor is at a superordinate level relative to the metaphorical expression. One metaphor can be thought of as the root of many metaphorical expressions. In other words, many metaphorical expressions share the same common metaphor. Lakoff states:

“If metaphors were merely linguistic expressions then we would expect different linguistic expressions to be different metaphors.” [2]

When we look at the metaphor LOVE IS A JOURNEY, we can see that many metaphorical expressions are built from that single metaphor. Here are three of numerous examples Lakoff gives that use the metaphor, LOVE IS A JOURNEY:

“We’ve hit a dead-end street.”

“We can’t turn back now.”

“Their marriage is on the rocks.” [2]

Again, one can see from these expressions that we are understanding the target domain LOVE from what we understand about the source domain, JOURNEYS. There are numerous other examples of metaphorical expressions that utilize this metaphor.

3. Poetic Metaphor

Figure 3: Similar triangles and their properties.

Up to this point, I have only talked about conventional metaphors and not addressed poetic or novel metaphor. Concerning poetic metaphor, Lakoff puts forth the same premise as conventional metaphor thus pointing out the relationship between thought and language:

“The generalization governing poetic metaphorical expressions are not in language but in thought. They are general mappings across conceptual domains.” [2]

Lakoff and Turner [5] tell us there are three basic mechanisms for interpreting linguistic expressions as novel metaphor: extensions of conventional metaphors; generic-level metaphors; image-metaphors.

A similar triangles poem is a poem in the form of a/b = c/d, where we are cross-mapping concepts across the variables to create poetic expressions. What I would like to show in this paper is that successful similar triangles poems use all three mechanisms listed above within the one construction. To illustrate my point, I will analyze “Pandemic Meditation,” which is a similar triangles poem. I will say a bit more about similar triangles poems soon, in Section 4. But before that, let us open up Lakoff and Turner’s three mechanisms.

Extension of conventional metaphor is recognized as an expression that is a novel use of a metaphor that we use in our everyday language. Lakoff and Johnson go into great detail illuminating conventional metaphor in their book Metaphors We Live By [3]. Suffice it to say that the extension of conventional metaphor evokes a creative realization that gives us an understanding of something common, yet in a very different way.

The next mechanism is image-mapping, and Lakoff gives us an example from Andre Breton:

For example, consider:

“My wife ... whose waist is an hourglass.”

This is the superimposition of the image of an hourglass onto the image of a woman’s waist by virtue of their common shape.” [2]

Let us note that image-metaphor and image-schema are different; I will address that later. That said, Mark Johnson states:

“[image-schemas are] the recurring patterns of our sensory-motor experience by means of which we can make sense of that experience and reason about it”. [1]

Our third mechanism is generic-level metaphors. These extend to a large array of metaphoric expressions. Here I will focus on a subset of the genericlevel metaphors, the GENERIC IS SPECIFIC metaphor. When we get a general understanding of something by merely reading a specific case for it, we are experiencing a GENERIC IS SPECIFIC metaphor. Proverbs operate in this manner because they make specific statements that can be used in numerous general situations. Lakoff and Turner explain:

Figure 4: Domain mappings.

“There exists a single generic-level metaphor, GENERIC IS SPECIFIC, which maps a single-level schema onto an indefinitely large number of parallel specific-level schema that all have the same generic-level structure as the source domain schema.” [5]

It is interesting to note that when applied, a pure mathematical equation automatically expresses a generic-level schema in a couple of ways.

Firstly, we see that the single equation structure provides numerous applied mathematical specific-level schemas. For instance, in physics, we have the equations for force: F = ma, distance: d = vt, or Ohm’s law: V = IR. And there are many more of these types of equations, all being specific-level expressions with the same generic-level structure, that is a = b times c.

In addition, within an equation, each variable has the ability to express infinite levels of values. In essence those values, or in the context of mathematical poetry, levels of importance or magnitude function in relation to each other as different specific-level schemes expressed in the form/scheme of a general-level equation. In other words, the equation is at the general level and any fixed set of values for the variables would be a specific-level schema.

At the end of the paper, I will address this metaphor in the context of “Pandemic Meditation”. Along the way, we will also see how each of the three mechanisms functions more generally in the context of similar triangles poems.

4. Similar Triangles Image-schema

I defined a similar triangles poem as a poem in the form of a/b = c/d, where we are cross-mapping concepts across the variables to create poetic expressions. I occasionally use the term “proportional poem” as a synonym. Yet, I believe that, at least in this present context, the similar triangles image scheme is more helpful in understanding how the poetic form interacts with the construct of poetic metaphor.

The equation used in “Pandemic Meditation” uses a similar triangles imageschema; see Figure 3 for a visual summary of the properties of similar triangles that will be relevant to us here. More generally, similar triangle poems intrinsically contain an image-schema, whereby the structure of a pair of similar triangles is part of the metaphorical mapping. What makes this method captivating is that aspects of this structure lend themselves directly to mapping metaphoric expressions across the horizontal bar and the equal sign of the equation.

Figure 5: Image mappings.

When we are using a similar triangles poetic scheme, the cognitive structure of the similar triangles provides the overall image-schema for the equation, and the terms for the equation provide the conceptual domains.

There are multiple ways these domains can be grouped to construct a metaphorical expression; see Figure 4 (we will say a lot more about this figure in Section 6). What is consistent in every grouping is that we map the conceptual values of the source domain to the corresponding conceptual values in the target domain. The image-schema inherent in the analogy of the proportional legs of the triangles will always be compared to the image-schema created by the proportional analogy of the conceptual domains that are being expressed. The terms of the equations have values that are open to interpretation but are generally experienced as contextual importance or magnitude.

As in all poetry, it is up to the reader to find meaning in the expression. Symmetry, in this context, can be explained as the concepts that remain consistent when other things change as we move between two domains. The important factor and the subsequent strength of the metaphoric expressions will be judged on the clarity in the symmetry expressed when finding a cognitive pattern across the corresponding ontologies between the source and target domains. The metaphor can be thought of as the union in the set of ontologies of the source domain and the set of ontologies of the target domain.

The union is the symmetry. In a mathematical visual poem, there will always be some imagery (image-metaphors) that we can map to each other or to the lexical or mathematical expressions (conceptual domains); see Figure 5 for a depiction of the image-mappings involved in a similar triangles poem. We will say more about this in Section 7.

5. Similar Triangles Equation

Figure 6: Palm tree and man at the beach.

Before getting further into the methods for analyzing these structures for poetics, let us examine how similar triangles can be used as a language to solve the dilemma of finding the height of a Mission Beach palm tree. The photo/diagrams we will use will offer us a good example of how to analyze similar triangles or proportional equations.

Notice a man and a palm tree in Figure 6. If I were to give you a tape measure and ask you to tell me how tall the palm tree is, would you be able to do it? It is easy if you understand the relationship between similar triangles and are able to set up the equation.

Figure 7: Proportions of shadow and height.

An interesting factor about similar triangles is that there is a proportional relationship between the sides of the two triangles. In the second diagram, you can see this proportion relationship in that the tree’s height is to its shadow as the man’s height is to his shadow. In algebra, we can set up the equation to express this relationship; see Figure 7.

The tree’s height divided by the tree’s shadow is equal to the man’s height divided by his shadow; see Figure 8.

We can physically measure both of the shadows and the man’s height, plug them into the equation given in Figure 7, and solve the equation for the tree’s height. This method will give us the answer to how tall the palm tree is.

Figure 8: Using similar triangles to determine the tree’s height.

6. Mapping Cognitive Domains

Figure 9: The particular aspect of the similar triangles image-schema used that shows up in “Pandemic Meditation”.

Within the similar triangles poem structure, there are eight important mappings that we can focus on. We use algebra to solve for each cognitive domain (variable) and analyze the results. A successful proportional poem is a creation whereby the source domain and target domain share a cognitive pattern. It is up to the reader to parse through the four syntactical arrangements and the four syntactical aspects shown in Figure 4.

There are two redundancies in the syntactical arrangements for we will find two mappings are reciprocals of the other two. This means that we will be swapping the target and source domains to see what happens. If the poem is strong, then two of the arrangements will resonate strongly, while the other two may only provide interesting nuances. That said, a strong expression will make sense in each of the four syntactical aspects. Figure 11 shows one aspect used in “Pandemic Meditation”.

Yet, all four aspects are meaningful, and we list two of them below, in Figures 12 and 13.

7. Image-Mappings

Since a mathematical visual poem automatically includes images, metaphors, and image-schema, we are able to image map numerous metaphorical expressions in its structure. Not only can we map image-metaphors across each other but also we can map them to image-schema in the mathematical and lexical domains; see Figure 5. In other words, we can map image-schema to abstract target domains that don’t contain image-schema. For instance, we can map an image-metaphor to one of the target domains in the similar triangles equation (once again, see Figure 5.)

Wealso need to be cognizant that image-schema metaphors are not the same as image-metaphors. As Lakoff and Turner state:

“Image-metaphors map rich mental images onto other rich mental images. They are one-shot metaphors, relating one rich image with one other rich image. Image-schema, as the name suggests are not rich mental images; they are instead very general structures, like bounded regions, paths and centers (as opposed to peripheries), and so on. The spatial senses of prepositions tend to be defined in terms of image-schemas (e.g., in, out, to, from, along, and so on).” [5]

Figure 10: Section of “Pandemic Meditation”.

This leads us to notice that within the similar triangles image-schema of “Pandemic Meditation,” a container image-schema can be found as well. Therefore we have image-schema within image-schema. In “Pandemic Meditation,” the container-schemas are expressed as, “In a shouting match” or “encircling the corpse that my soul drags”.

In this poetic expression, you will notice the number 13 provides a schema as well, for it is repeated in numerous ways, including the circled letters in the reflecting anagrams (“eleven plus one = twelve plus two”). There is an ominous sky, large raven, three skeletons, and a swinging/jumping monkey seen among the circling image-schema; see Figure 10 for some of the details.

The reader is to map the images to the domains searching for a cognitive pattern connecting us to the metaphors. The image-schema of 13 circles connecting the identical letters to each other map to the image-schema created by the domain of 13 vultures. The 13 vultures map to the skeletons which map to the raven with a 3-way connection to the concept of death. The A JURY OF 13 ACUTE ANXIETIES IN A SHOUTING MATCH map to the 13 vultures due to the connecting container schema. The Buddhist concept of monkey mind, an analogy of our disquieted mind, maps to the 13 circles schema as a path-schema for the monkey to follow. The Skeletons, Raven, and Vultures map to the target domain of A JURY OF 13 ACUTE ANXIETIES IN A SHOUTING MATCH or to the target domain of the NON-ATTACHED MIND (or lack thereof).

I am fascinated by similar triangles equations and by the numerous ways of solving them, which all together offer a versatile form for poetry. We map across the horizontal bar as well as the equal sign, enabling the target and source domains to move around the equation, creating new syntax and richer meaning. We also change meaning by assigning different values or levels of importance to the variable concepts as shown in the 4 syntactical aspects from Figure 4. That is, aesthetic value is found as one creates values for the poem while reading it, much like finding personal meaning in a traditional lexical poem. There are multiple values present in this semantically dynamic equation.

8. The Equation

Figure 11: Equation as it appears in “Pandemic Meditation”.

Let us now look at the proportionality equation in “Pandemic Meditation” and explore a few ways we can manipulate it algebraically. We have already seen Figure 9, which displays the equation written in the syntax of the poem and also in a serif font. Figure 11 below shows us the form as it appears in the poem itself.

Because proportional poems carry the image-schema of similar triangles, they can be read as a is to b as d is to e (as in Figure 3). The mappings of the target and source can be reversed so that the structure can be read lexically in four different ways (recall Figure 4.)

Let us first focus on two different ways we can view the similar triangles structure built into “Pandemic Meditation” and then look at four attributes to take into consideration.

Figure 12: Another form of the equation.

Two Examples of Arrangements

One of the new forms would be asserting that the value of NON-ATTACHED MINDis to the value of A JURY OF 13 ACUTEANXIETIESINASHOUTING MATCH as the value of MY CORPOREAL BODY is to the value of A DARK CLOUD OF 13 VULTURES ENCIRCLING THE CORPSE MY SOUL DRAGS.

Or we can mathematically manipulate the original equation from Figure 11 to get Figure 12.

Another form would be asserting that the value of NON-ATTACHED MIND is to the value of MY CORPOREAL BODY as the value of A JURY OF 13 ACUTE ANXIETIES IN A SHOUTING MATCH is to the value of A DARK CLOUD OF 13 VULTURES ENCIRCLING THE CORPSE MY SOUL DRAGS.

Or once again, we can mathematically manipulate the original equation from Figure 11, this time, to get Figure 13.

The Four Aspects

To illustrate the dynamics inherent in these equations, let us now view the four syntactical attributes inherent in the solutions for each variable of the expression — note that these values vary from zero to infinity and everything in-between — once again we are referring to Figure 4.

Figure 13: Another rearrangement of the equation.

When the value of NON-ATTACHED MIND becomes near-infinite the value of A DARK CLOUD OF 13 VULTURES ENCIRCLING THE CORPSE MY SOUL DRAGS becomes near zero.

When the value of A DARK CLOUD OF 13 VULTURES ENCIRCLING THE CORPSE MY SOUL DRAGS becomes near-infinite then the value of NON-ATTACHED MIND becomes near zero.

When the value of A JURY OF 13 ACUTE ANXIETIES IN A SHOUTING MATCH becomes near-infinite then the value of MY CORPOREAL BODY becomes near zero.

When the value of MY CORPOREAL BODY becomes near-infinite then the value of A JURY OF 13 ACUTE ANXIETIES IN A SHOUTING MATCH becomes near zero.

9. Poetic Metaphor Mechanisms in “Pandemic Meditation”

The paper set out to show how the mechanisms of poetic metaphor are present in similar triangles poems. While there are many examples, let us highlight at least one example for each of the three mechanisms of poetic metaphor described in Section 3 in relation to the mathematical visual poem “Pandemic Meditation”.

Extended conventional metaphor: Whenwemapthevaluesinthesource domains of A DARK CLOUDOF13VULTURESENCIRCLINGTHE CORPSE MY SOUL DRAGS and MY CORPOREAL BODY to the target domains of A JURY OF 13 ACUTE ANXIETIES IN A SHOUTING MATCH and NON-ATTACHED MIND, we are performing an example of an extended conventional metaphor. The conventional metaphor used in these expressions is the MIND IS BODY metaphor. These metaphorical expressions are not conventional in the sense that they are not part of our basic use of language. As you solve the equation in the numerous ways, you read many expressions of the MIND IS BODY metaphor.

Image-mappings: There are numerous examples of image-mappings in this poem, but I would like to focus on two:

(a) The image-schema of the similar triangles mapping one to another is an example of mapping an image-schema to a similar imageschema. In other words, similar triangles ensure the image-schema is consistent across the expressions.

(b) The image of the 13 circles moving between the letters of the anagrams to the 13 anxieties and again to the 13 vultures uses the same circling image-schema which is another example of imagemapping expressed in the poem.

The generic-level metaphor: This metaphor mechanism can be realized in this poem by noticing that the GENERIC IS SPECIFIC metaphor exists within the specific-level expression of A JURY OF 13 ACUTE ANXIETIES IN A SHOUTING MATCH AS ADARKCLOUDOF13 VULTURES ENCIRCLING THE CORPSE MY SOUL DRAGS. Due to vultures being symbols of death, we see that we have the conventional metaphor DEATH IS A DEVOURER. With our mapping, we see the expression, DEATH IS ANXIETY. This can be understood as not only 13 specific-level omens of death but countless specific-level omens of death for every anxiety that is encountered during the pandemic.

I will reiterate that the equation structure alone affords numerous values within the variable terms/domains. This means that the conceptual domains are variable and thus able to express countless fixed specificlevel expressions for the four conceptual domains within the equation.

For example, NON-ATTACHED MIND can be expressing a mind of enlightenment or a mind in hell; it can also express everything inbetween (see Figure 4. Of course, the proportional schema means that when you change the value (importance) of a conceptual domain, one of the other conceptual domains must change importance as well because of our expectation that the similar triangles schema must be consistent.

10. Conclusion

I would like to end this essay with a personal note. The aesthetic beauty that I have found within a mathematical visual proportional poem lies in an alternating cognizance between the two experiences below:

The beauty found in analyzing the lexical and mathematical multiple dynamic cross-domain mappings inherent in the similar triangles imageschema.

The conflation of lexical and sensorial visual imagery.

From the examples above, I hope readers can clearly see that similar triangle poems satisfy the requirements of poetic metaphor. I also hope that they are intrigued by the form and will try to construct or write their own similar triangles poems.

Acknowledgments: This essay was written as a response to a request from Jesse Russell Brooks, Director of the Film and Video Poetry Society, Los Angeles, California.

References

[1] Mark Johnson, “The philosophical significance of image schemas,” pages 15–34 in From Perception to Meaning Image Schemas in Cognitive Linguistics, edited by Beate Hampe (De Gruyter Mouton, Berlin, 2008).

[2] George Lakoff; “Contemporary Theory of Metaphor,” pages 202–251 in Metaphor and Thought edited by Andrew Ortony (Cambridge University Press, 1992).

[3] George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, University of Chicago Press, 1980.

[4] George Lakoff and Rafael Nu˜nez, Where Mathematics Comes From: How the Embodied Mind Brings Mathematics into Being, Basic Books, 2000.

[5] George Lakoff and Mark Turner, More Than Cool Reason: A Field Guide To Poetic Metaphor, University of Chicago Press, 1989.