You Are Here: Decentralization, Agency, and the Politics of Participation

Who decentralizes? For whom?

And what actually changes when we say that something has been decentralized?

Over the last years, decentralization has become a familiar refrain. One hears it repeatedly at global policy forums like the World Economic Forum in Davos, where it appears alongside promises of tokenized economies, digital ownership, and new models of AI governance. In white papers, panels, and pitch decks, decentralization is framed as a corrective - to centralized power, to opaque institutions, to economic exclusion. The message is often reassuring: technology will fix what politics could not.

But outside these rooms, the picture feels less certain.

In practice, I see decentralization show up unevenly. Some systems redistribute access while quietly recentralizing control. Others invite participation without offering real influence. Many depend on centralized platforms, capital, or infrastructure to function at all. This leaves me with an uncomfortable question: does decentralization, as it is currently practiced, exist beyond rhetoric? And if it does, who actually experiences its benefits - and who absorbs its risks?

Decentralization is usually described as technical infrastructure, but I have come to understand it just as much as a story we tell about power, agency, and progress. It shapes expectations before it shapes systems. To decentralize is never only to redesign a network; it is to rearrange responsibility, labor, ownership, and trust. Something is always being redistributed, even when it remains invisible at first.

This is where art becomes useful to me - not as illustration or celebration, but as a testing ground. Artistic practice is not required to resolve contradictions. It can sit with them. Artists can model speculative systems alongside real ones, exaggerate their limits, or strip them down to their assumptions. In doing so, art exposes the gap between how decentralization is imagined and how it is lived: not only whether something works, but how it feels, who it serves, and what it leaves out.

This article approaches decentralization through that lens. Rather than asking whether decentralization is good or bad, I am interested in a more practical and more difficult question: under what conditions can decentralized technologies serve their original intentions, and where do they fall short? By moving between concrete case scenarios and artistic explorations, the aim is to better understand the limits of decentralization-and what may still need to be built, reconsidered, or deliberately left behind.

The Persistent Centre: Why Decentralization Never Fully Decentralizes

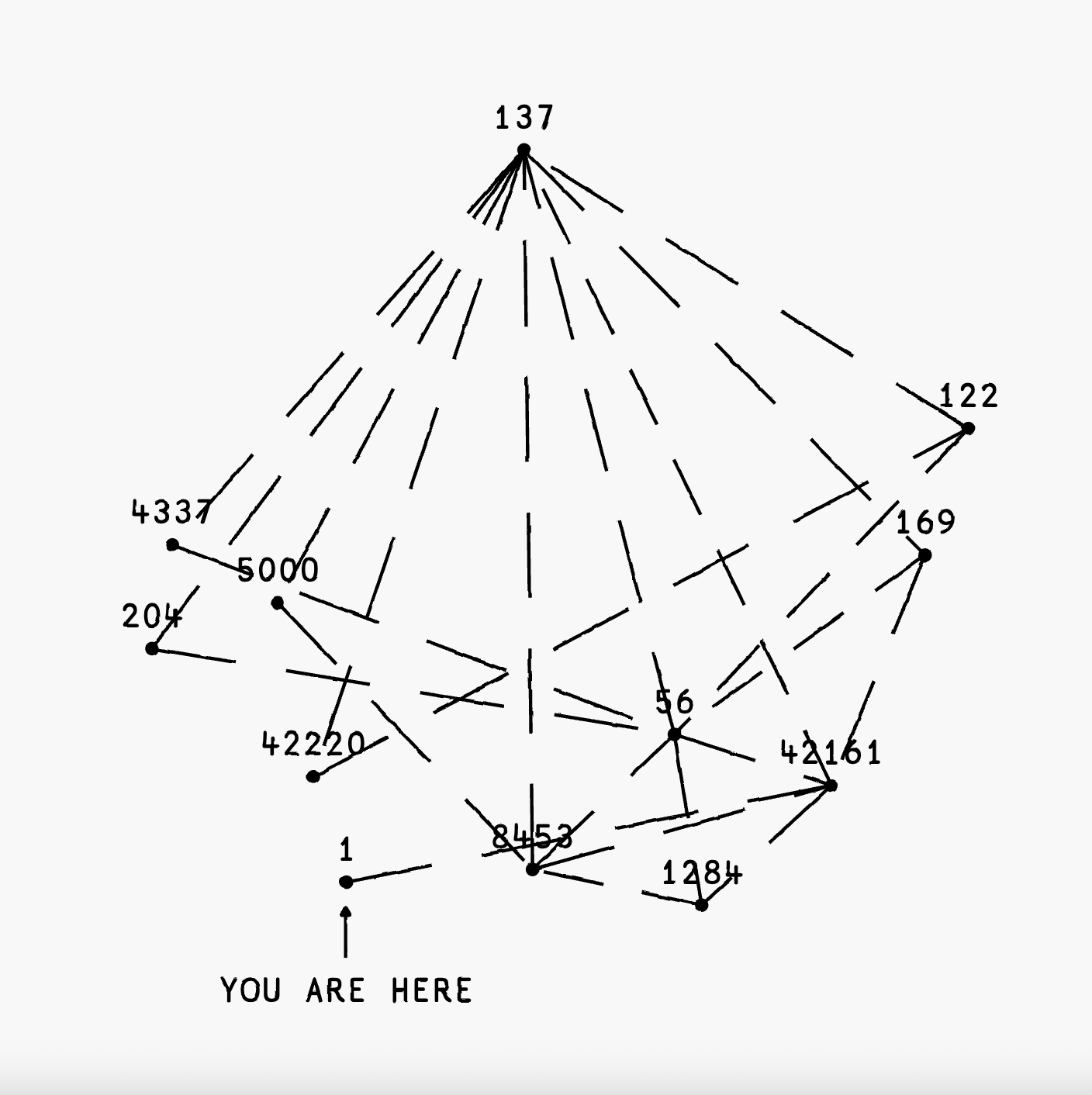

0xfff, You Are Here 42161, 2024

One promise of decentralization is the disappearance of the centre. Remove the core, distribute control, and power will flatten out. Yet in practice, the centre rarely disappears. It shifts, disguises itself, or reappears elsewhere.

Decentralization only makes sense in relation to what it claims to move away from. Even systems designed to avoid hierarchy remain organized around invisible points of gravity - capital, infrastructure, interfaces, or dominant narratives. What looks distributed on paper can feel strangely centralized in everyday use.

This isn’t only technical. It’s cultural. Many political, economic, and computational systems are built on the assumption that coordination requires a focal point. Even when authority is dispersed, legitimacy, trust, and decision-making tend to cluster. As a result, decentralization often becomes a rearrangement of control rather than its disappearance.

Blockchain makes this visible. While data may be distributed, influence often concentrates around:

• those who entered early or hold large amounts of capital,

• those with technical knowledge or control over infrastructure,

• and those who shape the story of what the system is and why it matters.

Participation expands, but authorship narrows. Responsibility spreads, but accountability becomes harder to locate.

Decentralized systems are also not immaterial. They rely on physical and institutional infrastructures: energy-intensive computation, hardware supply chains, data centers, undersea cables, and often cloud services and centralized access layers. Claims of efficiency do not eliminate these costs, they redistribute them, frequently away from those who benefit most. In that sense, the centre persists not only through capital and narrative, but through maintenance and dependency: decentralization can remove visible intermediaries while leaving the underlying responsibilities harder to see.

Simon Denny, Blockchain Visionaries, 2016.

This question of where power actually resides becomes explicit in You Are Here (42161) (2023) by 0xfff. The work distills decentralization into a deceptively simple gesture: a “YOU ARE HERE” marker tied to chain ID 42161 (Arbitrum), set within a map of other EVM chain IDs connected by traces produced through bridging. Rather than presenting blockchain as placeless or abstract, it insists on situatedness. You are not everywhere. You are here, within a specific protocol, under particular rules, dependencies, and governance assumptions. In doing so, the work makes infrastructure legible as a cultural condition. Decentralization does not erase location or responsibility; it redefines them. What appears distributed still has a centre, even if that centre is no longer visible, only felt.

Other artists make this mismatch - between how decentralization is described and how it is experienced - visible in different ways. Simon Denny’s Blockchain Visionaries (2016–ongoing) shows how “decentralized” systems borrow centralized power aesthetics, from trade-fair displays, corporate branding, founders staged as visionaries, protocols framed as inevitabilities. What Denny makes clear is that decentralization does not escape myth-making. It produces new heroes, new centres of attention, and new forms of legitimacy. The system may be distributed, but the story is tightly managed. In this sense, decentralization functions as a performance, something that must be continuously staged to sustain belief.

What Denny captures is not only a technical structure, but a perspective. He focuses on how power feels from the inside: confusing, opaque, fragmented, yet strangely directional. You may not see the centre, but you can sense its pull.

Removing a centre at the technical level does not dissolve hierarchy, without attention to culture, governance, and storytelling, decentralization can become another way of recentralizing power under a different name.

NFTs, Markets, and the Reduction of Art to Assets

If decentralization promised a rethinking of ownership, the NFT boom revealed how quickly that promise could be bent into familiar market behavior.

Between 2020 and 2022, much of the art world’s engagement with blockchain condensed into a simplified form: the JPEG as a tradable asset. What was presented as a new model of artistic autonomy often became a faster, more volatile version of the existing art market-scarcity, speculation, and visibility. The technology was new, the behavior was not.

NFTs made transactions frictionless and ownership legible, but in doing so they frequently reduced artistic value to exchange value. Context, process, care, and responsibility were sidelined in favor of speed and liquidity. Participation itself became financialized: to engage was to speculate, to belong was to buy in. Broader questions around preservation, authorship, access, governance were deferred rather than addressed.

Institutions responded cautiously. Museum acquisitions signaled openness to the medium, yet most engagements stopped at acquisition. Less frequently examined were structural questions: who maintains these works over time? What happens when platforms disappear? How are software-based artworks conserved? What does stewardship mean when ownership is distributed but responsibility remains diffuse?

This market-driven phase, however, should not be mistaken for the limits of the technology itself. Blockchain does not inherently function as a speculative asset vehicle. Used with intention, it can operate as infrastructure for trust, memory, and coordination - areas where the art world has long faced structural challenges.

Sarah Friend, Life Forms, 2021.

Some artists have worked deliberately against dominant NFT logics to make this potential visible. One approach can be seen in Sarah Friend’s Life Forms (2021), which was designed to resist extraction and speculation altogether. By embedding ecological limits directly into the code, the work rejects the assumption that blockchain-based art must be monetized in order to exist. Value is not accumulated through circulation or resale, but constrained through care, duration, and interdependence. Speculation is not discouraged rhetorically; it is rendered structurally impossible.

A different strategy appears in Jack Butcher’s Full Set (2025), which operates within, rather than against, the much-criticized mechanics of Rodeo’s micro-priced, 24-hour open editions, often dismissed as disposable “digital postcards.” Instead of rejecting these conditions, Full Set uses them as material. By structuring twenty-seven works as a capped, interdependent system capable of permanent transformation once a collective threshold is reached, the project shifts attention away from the individual image toward the dynamics of coordination, accumulation, and network effects. Value emerges not from scarcity alone, but from how platform rules, collective behavior, and time interact.

Taken together, these examples point to a more precise diagnosis. The problem was not that art entered the blockchain, but that the art world largely adopted the most reductive uses of the technology first. What these works demonstrate is that different value systems are possible, whether through refusal, constraint, or strategic engagement with existing platforms. The challenge now is not to abandon decentralized tools, but to reorient them away from short-term market optimization and toward longer horizons of care, responsibility, and cultural preservation.

Jack Butcher, Full Set, 2025.

Games, Gamification, and the Illusion of Agency

Almost everything today carries the logic of a game. Finance is gamified through dashboards, points, and quests. Political participation is reduced to likes, shares, and viral moments. Work, wellness, and social life are increasingly structured around incentives, progress bars, and rankings. This is more than a design language. It is a way of coordinating attention, motivation, and organizing behavior.

Games, in this sense, offer a useful lens for thinking about decentralization. They promise freedom, experimentation, and choice, yet they are always bounded systems. Rules are defined in advance, outcomes are constrained within carefully designed parameters. Players act freely, but never outside the logic of the game itself. Precisely because of this tension, games and simulations make visible how agency is structured, measured, and governed.

Blockchain’s entry into gaming therefore feels intuitive. Games already rely on virtual assets, internal economies, scarcity, and forms of ownership. In theory, blockchain infrastructures could extend these dynamics by allowing players and creators to retain value, participate in governance, and shape the worlds they inhabit. In practice, however, decentralization in games has so far been applied more successfully to assets than to authority. In games such as Axie Infinity, players own characters as NFTs and can trade them freely. Yet the deeper structures of the game - token supply, reward mechanisms, economic balance remain centrally designed and adjusted. When the in-game economy expanded and later contracted, players experienced the consequences directly, while decision-making remained largely out of reach. Ownership became distributed, but responsibility stayed diffuse.

Related dynamics can be observed in metaverse platforms such as The Sandbox and Decentraland. Land, avatars, and objects are tokenized, and governance mechanisms formally exist. Yet meaningful influence often correlates more strongly with capital concentration than with participation. Players contribute time, creativity, and social energy, generating value through presence and interaction, while the systems that define that value remain difficult to reshape collectively.

Across these examples, a consistent pattern appears. In games, decentralization is most often applied at the level of assets, while authorship over the system itself remains limited. Interfaces signal decentralization, yet decision-making continues to concentrate beneath the surface. This does not negate the potential of blockchain in games, but it raises abother question: why has decentralization been implemented so narrowly?

The same infrastructures that make engagement legible, comparable, and exchangeable could support other arrangements. What would it mean to extend decentralization beyond ownership, into governance, rule-making, and long-term stewardship? Rather than optimizing participation for short-term incentives, games could be designed as shared systems - ones in which players meaningfully influence economic parameters, assume responsibility collectively, and shape worlds that evolve over time.

In this sense, the question is not whether games should be decentralized, but how. Artistic games offer important clues. Rather than rehearsing utopian futures, they rehearse awareness.

Axie Infinity developed by Sky Mavis, 2018.

Across these examples, a consistent pattern appears. In games, decentralization is most often applied at the level of assets, while authorship over the system itself remains limited. Interfaces signal decentralization, yet decision-making continues to concentrate beneath the surface. This does not negate the potential of blockchain in games, but it raises abother question: why has decentralization been implemented so narrowly?

The same infrastructures that make engagement legible, comparable, and exchangeable could support other arrangements. What would it mean to extend decentralization beyond ownership, into governance, rule-making, and long-term stewardship? Rather than optimizing participation for short-term incentives, games could be designed as shared systems - ones in which players meaningfully influence economic parameters, assume responsibility collectively, and shape worlds that evolve over time.

In this sense, the question is not whether games should be decentralized, but how. Artistic games offer important clues. Rather than rehearsing utopian futures, they rehearse awareness.

Narratives, Ecologies, and Care

Decentralized systems are not immaterial. They rely on physical infrastructures: energy-intensive computation, mineral extraction for hardware, data centers, undersea cables, and cloud services. Claims of efficiency or scale do not eliminate these costs; they shift and redistribute them, often geographically and politically away from those who benefit most. When decentralization is discussed primarily in terms of access or autonomy, its material footprint tends to disappear from view, allowing extractive logic to re-enter under new technical forms rather than being fundamentally challenged.

The question, then, is not whether decentralization reduces visible intermediaries, but whether it makes responsibility legible.

What would it mean to design decentralized systems that account not only for participation, but for energy use, maintenance, authorship, and long-term care? This may require slowing systems down, prioritizing transparency over scale, and treating infrastructure as an ethical choice. In this sense, decentralization becomes less about removing centres and more about making dependencies visible and deciding, collectively, which ones we are willing to sustain.

At the same time, decentralization operates powerfully through narrative. I often encounter it first not as a protocol, but as a story: autonomy, participation, collective ownership. These narratives generate legitimacy and sustain trust long before anyone engages with the underlying system, often compensating for limited avenues of actual decision-making. Decentralization becomes less a condition than a claim, something repeatedly asserted rather than fully realized.

The challenge is not to abandon these narratives, but to test them. If decentralization is invoked as a promise, it should be accompanied by mechanisms that make decision-making, responsibility, and exit visible. Without this alignment, decentralization risks functioning primarily as a legitimizing story, one that stabilizes trust without redistributing power.

In this sense, the question is not whether games should be decentralized, but how. Artistic games offer important clues. Rather than rehearsing utopian futures, they rehearse awareness.

Where Decentralized Systems Actually Succeed

Decentralization is often discussed as an ideology, but that framing is rarely useful. More precisely, decentralization functions as a coordination technology: a way of aligning incentives, belief, participation, and time across distributed networks. The most resilient systems do not succeed by eliminating intermediaries altogether, but by coordinating human behavior over long-term horizons. Value compounds when friction is reduced, incentives are coherent, and shared narratives sustain participation. In this sense, the network economy is not defined by ownership alone, but by forms of contribution, capital, attention, labor, culture, and meaning.

The strongest decentralized systems do not feel like products, they feel like movements, because they reward participants not only financially, but socially and psychologically.

At the same time, decentralization is not a universal solution. It fails when governance becomes performative, participation is simulated, or power quietly recentralizes behind opaque mechanisms.

The challenge, then, is not to decentralize everything, but to apply decentralization where openness, transparency, and collective stewardship genuinely add value, particularly in domains at the intersection of capital, culture, and community, where context, memory, and responsibility matter, and where traditional institutions struggle to scale trust over time.

Rhea Myers, Is Art (Token), 2023.

Conclusion

I believe that, the future belongs neither to centralized control nor to decentralization as dogma, but to systems that understand how humans actually behave - socially, psychologically, and over time.

Experiments in algorithmic governance, such as those developed by Primavera De Filippi through projects like Plantoid, expose both the promise and the limits of decentralization. By embedding coordination and decision-making directly into smart contracts, these works attempt to redistribute authority structurally rather than rhetorically. Yet even here, parameters are set, interfaces frame participation, and legal and infrastructural dependencies remain. The centre does not disappear; it becomes conditional, procedural, and visible.

This is why art remains central to thinking about decentralization. Artistic practice does not simply adopt technological systems - it tests them. It slows them down, exposes their assumptions, and insists on care where efficiency would prefer abstraction. In a landscape obsessed with scale, art reminds us that stewardship is not automatic. It must be designed, practiced, and collectively sustained.

Primavera De Filippi, PLANTOÏD #15, 2014.

xxx

References & Works Discussed

The arguments developed in this essay are informed by artistic and infrastructural experiments that make decentralization tangible. Works by David Simon, aka 0xfff (You Are Here (42161)), Simon Denny (Blockchain Visionaries), Sarah Friend (Life Forms), Jack Butcher (Full Set), Rhea Myers (Is Art (Token)), and Primavera De Filippi (Plantoid) each explore, in different ways, how power, governance, ownership, and responsibility are structured within decentralized systems.

Platforms and organizations referenced include the World Economic Forum, Axie Infinity (developed by Sky Mavis), The Sandbox, and Decentraland.

Culture Doesn’t Preserve Itself. Help Us Build the Infrastructure.

Your donation helps support the ongoing independent, non-profit initiative dedicated to exploring how digital art is written, contextualised, and preserved.

Contributions fund ongoing research, development of protocol, and archival infrastructure, ensuring that the art and ideas shaping this era remain accessible, verifiable, and alive for future generations on-chain:

Donate in fiat

You can contribute via credit card here:

https://www.katevassgalerie.com/donation

Donate in eth

Send ETH directly to:

katevassgallery.eth - 0x56A673D2a738478f4A27F2D396527d779A1eD6d3

or by buying the book:

www.book-onchain.com