The Interview I Art Collector Zaphodok

The interview with the art collector Zaphodok

In the shifting tides of both contemporary and digital art, one constant remains: the crucial influence of collectors. They are the architects of the ecosystem, molding and guiding its evolution with every acquisition. Their passion, foresight, and unwavering dedication don't just sustain artists—they actively propel the cultural trend. In a series of interviews, Kate Vass seeks to peel back the layers and get to the heart of what drives a new wave of collectors—their connections with artists and the deeper motivations behind their digital art collections.

In this discussion, we had the distinct pleasure of speaking with zaphodok, a passionate art collector who has been pushing the boundaries of art at the intersection of internet culture since the beginning. His collection, a treasure trove of generative and AI-driven works, offers a rare glimpse into the future of art.

We hope you find as much inspiration in this interview as we did in bringing it to you.

KV: Can you recall your first encounter with art and describe what motivated you to start collecting?

ZP: I'm afraid I cannot; the creative industries have been my natural habitat since a young age, and I am grateful to have been able to turn my innate passions into a career. The motivation to start collecting digital art specifically, stems from the fascination with the revolutionary underlying technology that allows us to do so in a native way.

KV: You began collecting digital art relatively early, starting in 2018. What inspired you to start collecting digital pieces?

ZP: The first non-fungible digital collectible I can think of was a documentation of one of my own analog works, minted on Bitcoin via Ascribe in mid-2015. Having been familiar with the concept of Colored Coins, I was drawn to Ascribe's innovative approach to authenticating creative works of any kind. It ultimately remained a one-time experiment.

Fast forward two years and a few months after going astray in the Cryptokitties craze, I dabbled into SuperRare. A publication platform and marketplace for digital art powered by Ethereum smart contracts with a simple and compelling value proposition for artists and collectors alike. Peer-to-peer trades between artist and collector, permissionless transfer of ownership, instant payments with magic internet money, and baked-in royalties on secondary sales, among other features were, an inspiring vision of a sustainable autonomous zone for art in the digital age.

KV: Do you have any formal education in technology, finance or art? Do you collect items other than digital art?

ZP:I am an architect, artist, and educator with over two decades of work experience. In 2020, I left my tenured academic position to prioritize family matters and my newfound passion for art on the blockchain. I do not collect items other than digital art except a few analog companion pieces, oddly labeled as “phygital”.

KV: How did you acquire the very first piece in your collection, and what was this work?

ZP: It was on April 28th, 2018, at 4:50 PM UTC (had to look this up on the blockchain), that I was determined to buy a tokenized artwork on SuperRare. Browsing through the nearly one hundred highly diverse pieces available felt like taking a walk on the wild side. Eventually, I left-click-bought a digital painting entitled 'Ship' showing a tanker sinking or cruising in the desert, created by an anonymous internet artist. For a brief moment the surreal subject matter brought to mind 'Aircraft Carrier City in Landscape', a provocative project by Austrian architect Hans Hollein from the early 1960s. But I didn't bother with any further research or classification whatsoever; I was simply relieved that the wallet successfully processed the transaction and that the piece appeared in my wallet address on Etherscan. To be honest, even with a decent understanding of the underlying tech, the notion of spending 0.1 ETH (around $68 at the time) on a JPEG from the internet was quite intimidating.

Aircraft Carrier City in Landscape project, Exterior perspective by Hans Hollein , 1964, copyright @MoMA

KV: What defines your collecting style? Is there a common theme or element that unites your collection?

ZP: I embarked on this journey with an open mind, and no expectations, and allowed myself to be drawn into this new realm of digital collecting. When I approach artworks, I don’t typically experience a strong emotional response or get caught up in introspective contemplation. For the most part, I view them as critical, thought-provoking vessels of encoded knowledge, brought to life through the most radical form of human expression. As Florian Schneider, a former member of the electronic band Kraftwerk, remarked, "If I wasn't making music, I could just say it" highlighting the unique property of artistic practice to convey what ought to be said in a way that language alone cannot. I am currently exploring various thematic avenues, including medium nativity, EVM art, renitent systems, and historical digital art. However, I believe the unifying theme of my collection is the pursuit of art as a catalyst for creating new perceptual and conceptual categories in the digital age.

KV: How do you see your role as a collector in the space and how did your collecting style evolve over the last 6-7 years?

ZP: As an advocate of cypherpunk values and ideals, I prefer to maintain a low public profile. If cypherpunks are touted to write code, then collecting art is my humble contribution to timestamp the associated ideals on the blockchain. I do not define myself by any specific role. Every now and then, people approach me and credit me with integrity and good instincts, which is more of a compliment than I could wish for.

Just as no man ever steps in the same river twice, collecting is a dynamic and iterative process. It’s a journey that demands curiosity and the courage to evolve and grow. As I encounter new artists, curators, and collectors, I find myself drawn to their unique perspectives and experiences. Throughout this ongoing journey, I strive to keep a balance between open-mindedness, experimentation, and a commitment to the core values of the Cryptoart movement.

KV: If you had to highlight one or two artists or an artwork from your collection, who would they be and why?

ZP: Rhea Myers’ “Is Art” (2014). A piece that represents the epitome of blockchain sculpture, a minimalist test install of Cryptoart, on the test fabric of Ethereum, anticipating the main properties of smart contracts and digital ownership on an open permissionless world computer. All of Rhea's works are, first and foremost, a delight for the synapses.

Anna Ridler’s “Bloemeveiling”(2019). There is nothing to be seen here, nothing to look at or listen to. A series of tokenized, tantalizing AI-generated tulips that wither and die the moment you gaze upon them is just a poor digest of the critical depth, the historical references, and the overall brilliant execution. A masterpiece that I was fortunate enough to witness at the time it took place.

(After watching the Tulip for one week, the smart contract automatically burned the token from the owner's wallet - Burn transaction)

KV: Could you share a memorable story from your collecting experience, perhaps a funny/sad story, or a near miss?

ZP: A memorable story happened during the 2018 Christie's Art+Tech Summit in London. After announcing it on Twitter some weeks prior and twice earlier on the day of the event, Jason Bailey informed the audience during the concluding panel that the gift cards containing the tokenized artworks by Robbie Barrat could be found in the giveaway bags at the entrance—one bag for each participant. As an admirer and early collector of Robbies’ work on SuperRare I looked around the room, but there was zero reaction from the audience. I got up, quietly left the conference room, grabbed my belongings, and hurried down the stairs. The bags were lined up on the counter, with no one else around. I politely asked the receptionist if I could possibly have four of them. She agreed with a smile. I quickly disposed of the unnecessary inserts in a nearby park and rushed back to my hotel room to redeem four frames of “AI Generated Nude Portrait #7” which later became the lore of “The Lost Robbies”.

It wasn't until weeks later, after the initial excitement had faded, that I realized I had claimed more pieces than I should have. To truly preserve the value of an artwork in a decentralized network, its stewardship must also be distributed—one bag, one participant, and one pair of shoulders. With this idealistic conviction, I set out to divest the excess pieces. I donated one to XCOPY's 2019 charity auction through his XERO Gallery and later sold two others for a modest sum to well-known collectors. However, the remaining piece is a permanent fixture in my collection, never to be parted with.

KV: Have you ever collaborated with artists or other collectors in the NFT space? Can you share a particularly meaningful experience?

ZP: Since 2019, I have been involved in various blockchain art projects, both as a member of multidisciplinary teams and as an advisor to curators and institutions. I've also commissioned several pieces from artists. However, I have yet to collaborate with fellow collectors in a way that feels truly meaningful and productive. I plan to prioritize this in the months and years ahead. Nevertheless, the most enduring experiences will always be those in-person occasions when people from the space come together and share a good time.

KV: Where do you see the future of the digital art market heading?

ZP: Industry reports indicate that, compared to the traditional art market dominated by analog art forms, media arts remain still niche and insular. How can one expect that the 2021 NFT hype would make any difference in this dynamic? However, the growing awareness of digital assets, demographics, efforts in financial and digital literacy, and innovations in showcasing technologies i.e. are likely to contribute to a broader acceptance of born-digital art forms. It is reasonable to expect the current active web3 user base to increase substantially over the next decade. The writing is on the wall of the Vienna Secession Building "To each age its art, to art its freedom", a reminder of the inevitable evolution of artistic expression alongside human progress.

'CENTS' by Rutherford Chang, 2024

KV: They suggest that the traditional art world's reluctance to embrace digital culture stems from the challenges of integrating digital aspects into everyday life. How do you exhibit your collection? Are there any pieces that are always on display in your home, and if so, how do you present them?

ZP: There is arguably a need for suitable display solutions for native digital art, to evolve beyond its tech-savvy niche status and appeal to a broader audience. The current state of the market, with start-ups experimenting with subpar technology, established screen providers lacking cultural understanding, and high-end products with short lifespans, fails to meet the needs of this space.

In my personal IRL environment, I use a couple of NFT art screens for curated playlists, along with some self-assembled devices for real-time screen-based works, complemented by a few prints and analog collectibles. However, the vast majority of pieces have not had the chance to adequately see the light of day in my home.

***

*The responses provided in this interview have been preserved in their original form, with no alterations to the interviewee's stylistic choices or grammar. - Kate Vass

zaphodok on X: @zaphodok

Website: https://zaphodok.art

Collection link: https://gallery.so/zaphodok

The Interview I Art Collector TaCyTurn

The interview with the art collector TaCyTurn

Cover: payaso, 2021 by Manoloide

Collecting art isn't just about acquiring objects; it's about curating stories that enrich our cultural tapestry. Collectors are the custodians of creativity, preserving and promoting the voices of artists who shape our understanding of the world. Their passion fuels a dynamic exchange where art transcends mere decoration to become a reflection of our shared human experience.

Through a series of interviews, Kate Vass seeks to understand the perspectives of a new generation of collectors, the relationships they build with artists, and what drives the formation of their collections.

In this conversation, Kate Vass had the pleasure of speaking with the art collector, aka, TaCyTurn, the degenerative Maths Lover, creator, and member of @fingerprintsDAO.

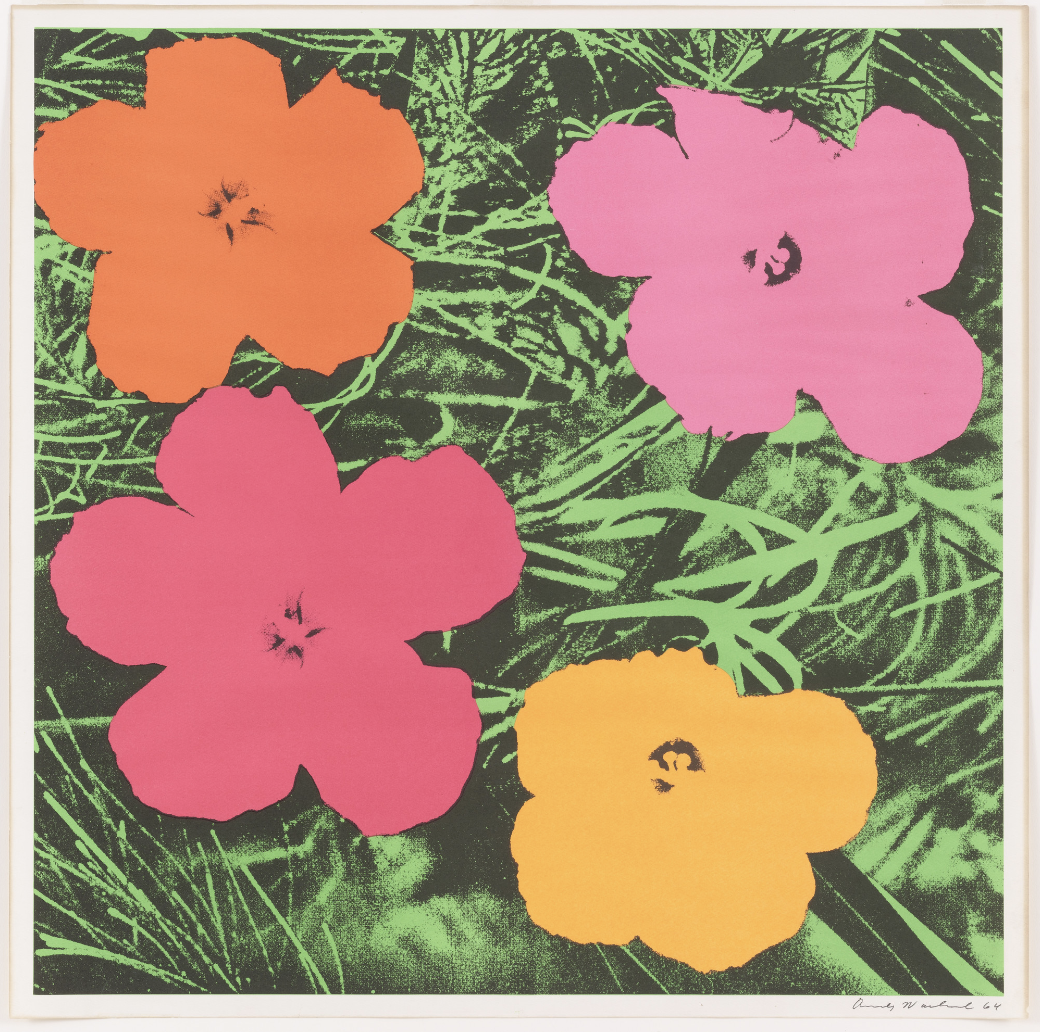

payaso, 2021 by Manoloide on hicetnunc

KV: What initially sparked your interest in art collecting?

TT: As a young kid in the 80’s, I’ve been fascinated by computers, programming, and graphics.

I started to play around with BASIC language and was triggered by graphics and animation created by demo scene creators, especially on Amiga or Atari…

But for 30 years I built my career and family and although I grew up with the internet, I didn’t pursue that much this path.

Then in 2017, I discovered Bitcoin and blockchains and honestly, I took a slap in my face!

How was it possible I didn’t find out about this earlier!!!

I spent some time in this rabbit hole, fascinated both by the technology but also the opportunity of making big money. sometimes I came across digital Art during this period: Money Alotta, Rare Pepes, Cryptopunks … but didn’t pay attention.

Then in early 2021, Beeple’s infamous sales ignited the NFT mania and then I discovered generative Art ...and took a second slap! I got back the tech, maths, and computer graphics vibes I loved 30 years ago and I happily dived into the so-called “NFT space”, on Ethereum and on Tezos with HicetNunc ( fun fact, I minted myself an artwork before collecting my first … hen #365 ).

KV: How do you decide which pieces to add to your collection?

TT: As a mathematics lover, I’m very attracted by pieces that play, and highlight the beauty of maths, whether the form: geometric, conceptual, or algorithmic, …

But my main interests are experimentation, technology, roughness, and weirdness … and of course my guts!

KV: What role does personal taste play versus investment potential when acquiring art?

TT: Way too much, lol !!!

I mean I collected a lot of pieces only because they are appealing to me, without overthinking.

I rarely buy pieces just for investment potential, although I’m convinced a lot of pieces and artists will become valuable in the long term.

KV: Can you share a story behind one of your most cherished pieces?

TT: In March 2021, I discovered DEAFBEEF’s art @_deafbeef. He was just beginning at the time and not much was known.

I jumped into his discord, and then he organized a giveaway for a SYNTHPOEM. I will always remember that morning when I woke up and saw a discord notification and a new Direct message from Tyler: « Hey you won, pls send me your ETH add » !!! This SYNTHPOEM allowed me a few times later to collect a GLITCHBOX, which is one of my favorite artworks and I became very involved in DEAFBEEF’s community, using his artworks to make experiments like “the Glitchbox Orchestra”. The story could end there but …

In 2021, I also discovered Mitchell F Chan's Digital Zone of pictorial. Reading the blue essay was a blast and triggered me so much that I translated it into French.

In November 2022, Mitch announced the release of a gorgeous physical Blue Book for each token holder … Then my goal of acquiring a Digital Zone became an obsession. For 2 years, I asked several owners if they would agree to swap their Digital Zone for my Deafbeef SYNTHPOEM. I was surprised a handful were interested but according to the price gap were asking me to add some ETH …

Finally, in May 2024, another collector agreed to swap 1 vs 1 and with the help of Mitchell himself we processed the deal, and I am finally the proud owner of IKB 54.

I find it very telling and ironic that 2 of my most valuable pieces were gifted to me for free.

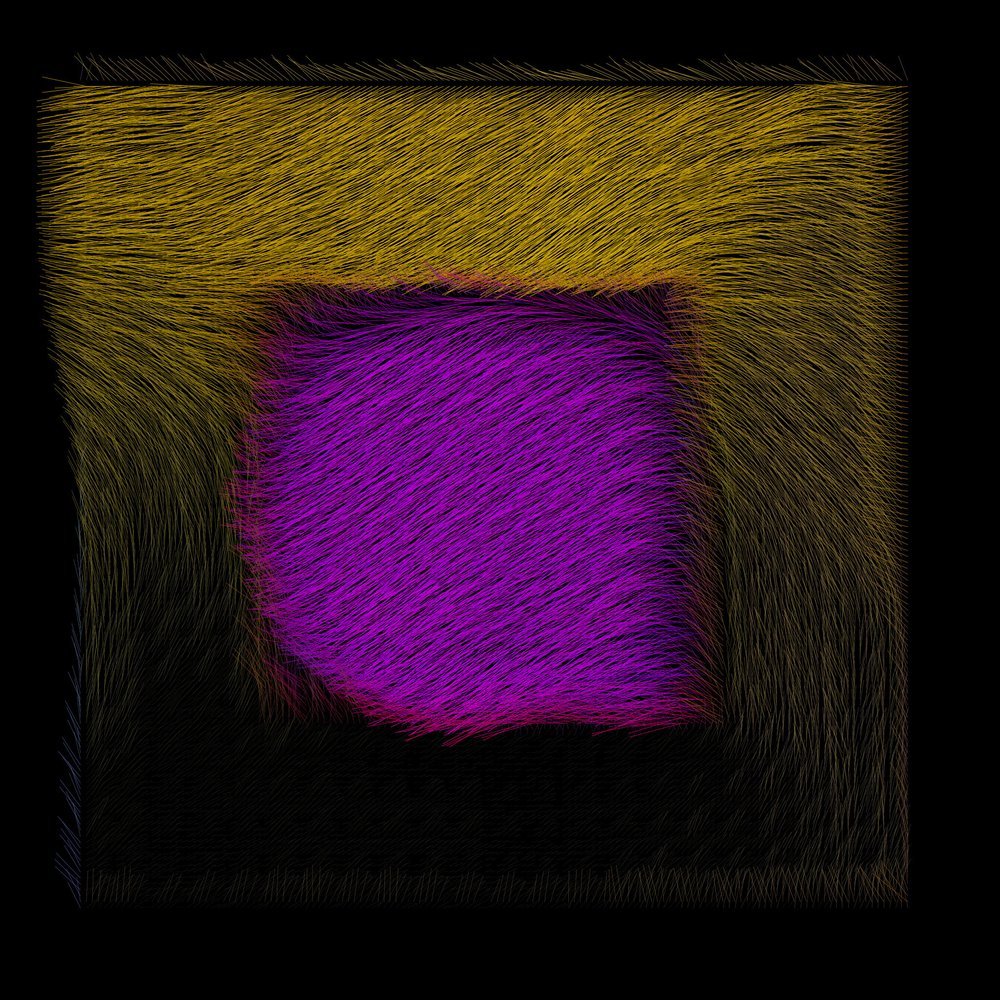

Glitchbox 205, 2021 by Deafbeef

KV: How has your collection evolved?

TT: My collecting volume has slowed down in 2023/2024, but I’m happy still to be able to acquire great artworks and opportunities when they appear.

fx(hash) and objkt.com are goldmines and allow me to discover and collect amazing pieces with a low budget. Verse is also a major platform for me.

I’m also more patient and can wait months, or years to collect a piece I’m eyeing. So in a word, I would say I'm more selective.

KV: What trends do you see currently shaping the art market?

TT: AI art, early or recent is a major trend right now, as it accompanies a ground-breaking emerging technology …

Generative Art hype is down from the @artblocks_io 2021 craze, and I feel a lot of collectors feel bored and worn, they believe everything has been made and there are no more surprises or innovations left… I’m convinced that artists will prove them wrong.

Last, I consider « net Art » ( Art that plays with the Internet ) and « blockchain Art » ( Art that plays with blockchains ) are for the moment very sharp niches with few artists and way few collectors but will gain traction and importance over the years.

KV: How do you balance supporting emerging artists with acquiring established works?

TT: As a very early bird on Hicetnunc, supporting anonymous/emerging artists has always been part of my collecting habits.

Now, I’m still trying to balance my collection in volume, but the ratio in value is almost established by artists.

KV: How does the digital art world, including Crypto Art, influence your collecting habits?

TT: The main influence on my collecting behavior comes from friends, some artists I love, and a few institutions like LeRandomart, Verse.works, Feral File, Kate Vass Galerie …

In all that abundance of information and noise, they’re lighthouses that help me to keep track of what really cares for me and learn.

Anticyclone #470 by William Mapan (Seedphrase Collection)

KV: What challenges have you faced as an art collector?

TT: Funding is a major challenge as my pockets aren’t that deep and I rarely play the speculation game …

But for me, the main challenge now is to organize, curate, and build a beautiful and meaningful gallery where others could enjoy and appreciate the 20-30% pieces of my collection I want to display.

I know and have tried a lot of platforms: DECA gallery, oncyber, …

But it is really a hard and very time-consuming task to do …

A very good example of a perfectly displayed and organized gallery is @lemonde2d DECA gallery.

I hope I will soon find time and inspiration to pursue my own.

KV: What advice would you give to someone just starting their art collection? Can you recall your first encounter with art and describe what motivated you to start collecting?

TT: I think Artnome's infamous quote perfectly sums it all:

‘BUY ART YOU LOVE, from artists that you want to see succeed, for prices you can afford, with the assumption that you'll never be able to resell it again, and you will always be happy’ - Artnome

Also, I would add to find your thesis, your guiding line (whether it’s a theme, a technology, etc …) that will drive you and help you to grow your collection and stay focused in this ocean of digital art pieces …

For example, I would label mine as «an experimentation in technologies »

KV: What matters most to you as a collector? Is it a curated program or clear provenance? Or perhaps the work needs to be on-chain and on a specific blockchain like Ethereum or Tezos?

TT: I value a lot of experiments in the artwork or artist’s process, and for sure the fact that the artwork is on-chain is a major plus for me.

I’d say I'm chain agnostic in theory, but, in reality, it’s so hard and time-consuming to keep track of all platforms and wallets so I‘m mostly collecting only on Ethereum, Tezos, and Bitcoin/Ordinals …

Finally, I would like to mention that a side effect of collecting digital art is that I started to create myself with maths, code and lately code+AI.

I'm very happy and proud to be able to express myself with these artworks.

Also, to experience the joy of being collected by others.

And last, releasing a long-form generative series made me realize even more the difficulty and beauty of such collections: finding, and tweaking the good set of parameters to find the sweet spot where there are consistent outputs but diversity and variance are so too!

***

*The responses provided in this interview have been preserved in their original form, with no alterations to the interviewee's stylistic choices or grammar. - Kate Vass

TaCyTurn on X: @TacyTurnh

The Interview I Art Collector Jediwolf

Interview with art collector Jediwolf

Truly great collectors don't just aim to make money; they strive to live with major masterpieces, discover the work, and integrate it into their life experiences. The role of the art collector has always been crucial; without them, the art world wouldn't function, and artists wouldn't survive. Even the most impressive art museums owe much of their grandeur to donations from individual collectors.

Through a series of interviews, Kate Vass seeks to understand the perspectives of a new generation of collectors, the relationships they build with artists, and what drives the formation of their collections.

In this discussion, Kate Vass had the privilege to interview Jediwolf, a collector with a vision and dedication to collecting digital art on-chain. Jediwolf has significantly contributed to the provenance of early GANs creations. In a relatively short period, he has built an impressive UnderTheGAN collection, which focuses on early AI artworks verified by their tokenized nature. His influence in the digital art space is notable, particularly for his passion for the artist XCopy and his role in the formation of one of the most successful DAOs, The Doomed DAO.

We are fortunate to be the first to interview Jediwolf, who typically prefers to remain anonymous. Jediwolf describes his early love for art and his journey into collecting digital pieces, as his collection aims to honor the pioneers of AI art, emphasizing the critical need to understand and preserve the origins and evolution of this art form within the digital and blockchain realms. We hope you enjoy the conversation as much as we did.

KV: What's your earliest memory of art, and what led you to start collecting?

JW: I've been a collector since an early age. As a teenager, I acquired my first oil paintings online. They weren't expensive, but I adored them. Marine art resonated with me the most, and paintings by artists such as J.M.W. Turner and Ivan Aivazovsky were, and still are, breathtaking to me. Although I couldn't afford to buy their works, they were my first true love in the world of art.

Ivan Aivazovsky, The Sea. Koktebel, 1853

KV: What constitutes “art”? What makes a work of art – “art” from your perspective?

JW: You know, art and its perception is totally a personal thing. It's like... imagine you've got this secret, beautiful tune playing in your head when you look at something. The louder that song plays, the more the art hits home. It's tough to put into words, but I think it just clicks on a subconscious level. Everyone has their own 'song', I believe.

KV: How did you acquire the very first piece in your collection?

JW: My collection mainly consists of @XCOPYART art (overeXposed collection) and early AI art (UnderTheGAN collection). The first XCOPY piece in my collection was 'Taxmen' 2019, 20/20 KO edition, acquired in May 2022.

KV: How would you describe yourself as an art collector?

JW: I see myself as a curator-collector and researcher. I'm learning to trust my intuition, especially when it comes to collecting, and not just following the crowd. It's fine to follow others when it helps you discover new things and learn, but if you're doing it just for speculation, there's a good chance it won't work out. After all, the art market is incredibly tough to speculate in.

KV: What defines your collecting style?

JW: I would describe my collecting style as 'counter-intuitive’. Generally, I prefer to buy works that resonate with me but aren't yet in the spotlight. For example, I started collecting XCopy early editions in 2022 (after the NFT bubble burst, and I was the only 'big' buyer for quite a long time) and early AI art in 2023 (probably spending the largest amount of funds in this genre as an individual collector), both of which weren't obvious choices for most participants in the blockchain-based art space.

KV: Have your reasons for collecting art evolved over time?

JW: Again, this motivation is hard to explain as, for me, it works on a subconscious level. When I see a piece that resonates with me and fits my collection, it becomes a bit of an obsession. It's something built into me, and I don't think it will ever change. However, curating my own collections, improving them, and supporting others gives me a lot of joy, and it's a somewhat new experience. The Doomed DAO is also a cool example of a mutual initiative where we collect XCOPY art as a group of over 120 people. I was one of the founding members.

KV: Describe your collection in three words.

Built with love.

KV: Is there a common theme or element that unites all the works in your collection?

JW: For my UnderTheGAN collection, I've focused specifically on 'early' AI art, created a few years before Midjourney and Stable Diffusion were released and before this 'genre' exploded beyond imagination. There are absolutely fantastic artists and pioneers who were training their own advanced AI models (2014-2019), putting lots of heart and soul into the process when no one really knew 'AI art' was even possible. I can see and feel it in each of these works.

KV: Do you have relevant education in tech or art? Do you pursue other hobbies or collect other things, and if so, why?

JW: For all my professional life, I've been in tech, and it probably made it a bit easier for me to understand tokenized/blockchain-based art faster than many other trad art collectors out there. I believe that eventually, we will reach a mass adoption where digital / blockchain-based art will be as 'normal' as trad art in the average person's perception. I would even say that youth will enter the art world through digital art, so I expect a major shift here. The reasons are quite obvious, I believe.

KV: What aspect of collecting do you enjoy the most?

JW: Probably the chasing aspect. Once I discover a work I really like, I do the research and conclude that it's something I really want to possess. The chasing part that comes next is definitely the most exciting. The acquisition journey (which can be very long, if it happens at all) brings emotions that will stay with me forever

KV: Can you share a funny/sad story or a “the one that almost got away” story from your collecting experience?

JW: One of the most emotional moments for me was acquiring 'Last Selfie' in 2022. I had been pursuing it for months (with no success), as it was the most coveted XCOPY artwork in my eyes and resonated with me deeply. Then, out of the blue, it was listed at an unimaginable price for a 10/10 edition: 200 ETH (around $700k today). My hands were shaking as I prepared and transferred the funds. An hour later, I discovered it was the very first minted edition of 'Last Selfie' (#1). The joy I felt was indescribable, and even now, that joy remains.

KV: Could you tell us more about your UnderTheGAN collection? Do you plan something additional with your collection?

JW: UnderTheGAN isn't just a collection; it's my personal AI art research project, recently brought to life within the early AI art timeline on Ethereum.

Today, AI art has surpassed all our predictions and continues to evolve at a breathtaking pace. But for me, what's truly crucial is understanding its origins - tracing back to where it all began. A small group of AI art pioneers, including Robbie Barrat, Mario Klingemann, David Young, Gene Kogan, Bard Ionson, Pindar Van Arman, Memo Akten, Mike Tyka, Alexander Mordvintsev (and others) were the true godfathers of the AI art revolution we're witnessing today. My mission is to share the knowledge I've accumulated through my research, shining a light on these foundational figures and their groundbreaking work.

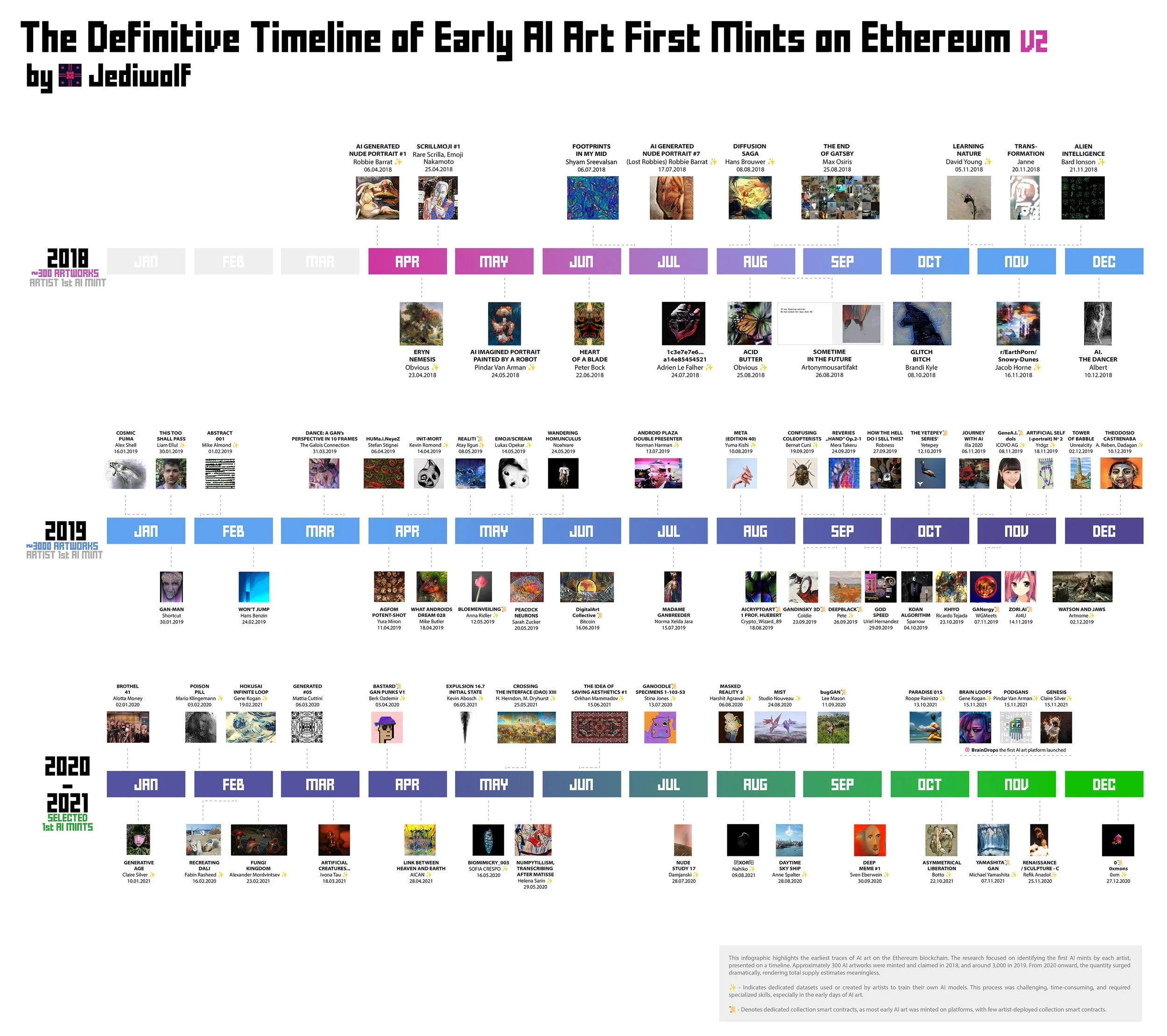

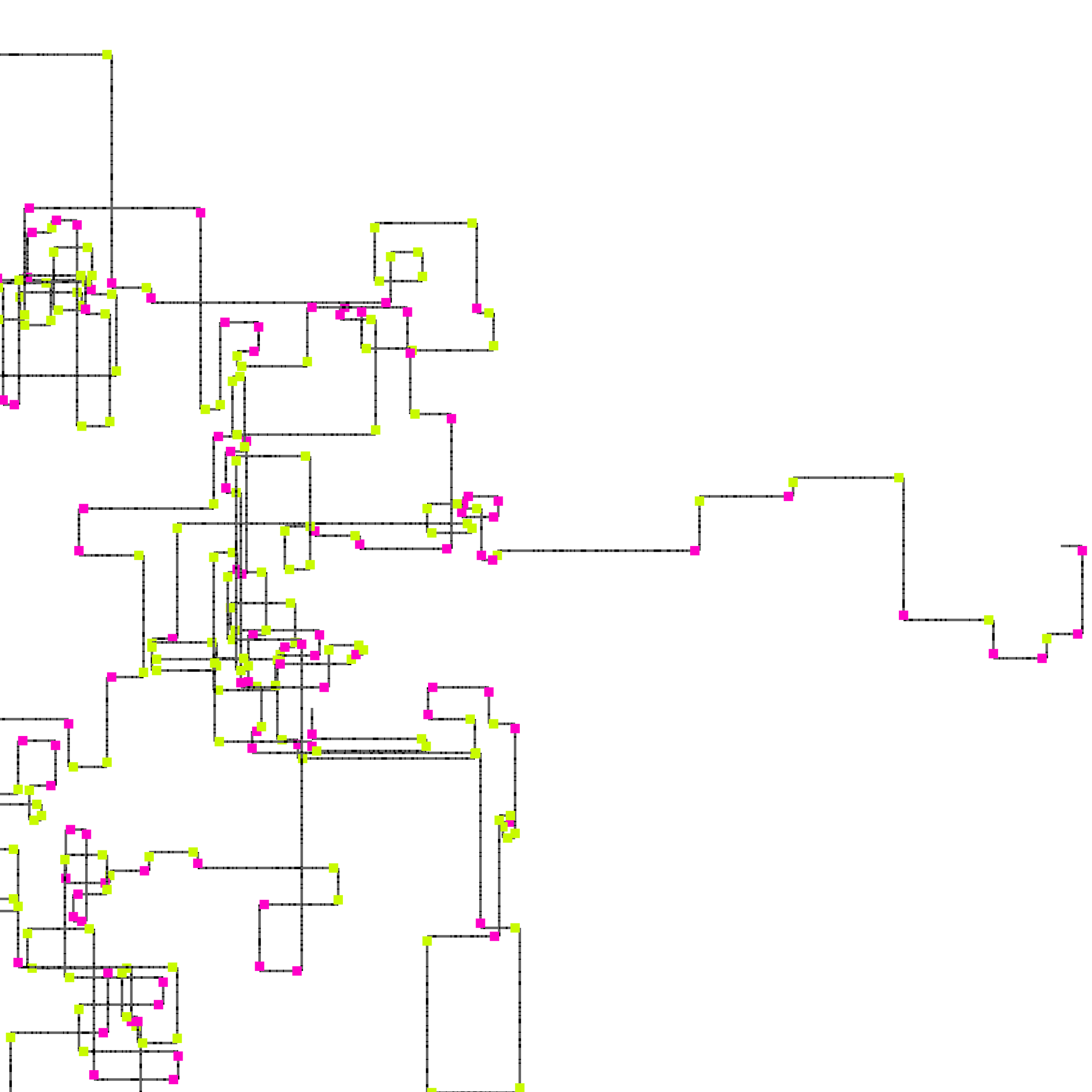

The Definitive Timeline of Early AI Art on ETH V1, courtesy of Jediwolf (https://x.com/randomcdog/status/1798340316967116897)

KV: What is the most recent piece of art you added to your collection and why?

JW: My most recent acquisition is 'Cats' by Alex Mordvintsev, the creator of DeepDream. This piece was generated in May 2015, predating the July 2015 open-source release of DeepDream's code. It took nine years to secure Google's permission for Alex to 'release' this artwork, and I'm immensely proud to be its owner.

'Cats' is unique in my collection as a "retroactive mint" - generated in 2015 but only minted in 2024. I typically avoid retroactively minted artworks unless they meet two crucial criteria: historical significance (such as being among the first DeepDream works ever generated) and strong provenance. In this case, both boxes are checked.

KV: Has digitalization/blockchain changed the way you collect? Can you imagine collecting AI art without blockchain or NFTs?

JW: Yes, I must say I became very spoiled as a collector. The fact that you can trace the artwork from its inception, have 100% guaranteed authenticity, and can trade globally (and instantly) without any third-party risks takes a lot of burden off collectors' shoulders. It's hard to keep buying art IRL when blockchain is an alternative. So, I'd rather avoid it at this point, with some exceptions, of course. IYKYK

Robbie Barrat & Ronan Barrot, Infinite Skulls, 2019 ( Jediwolf’s the UnderTheGAN Collection )

KV: What or who has influenced you as a collector? Are there any collectors you admire or watch out for?

JW: Yes, there are many wonderful collectors whom I admire. If one is interested in early AI art, I recommend Zaphodok, Batsoupyum, WangXiang, Hackatao, 6529, TokenAngels, Coldie, Artonymousartifakt, Colborn and MOCA collections. For XCOPY - Liquid (@l1qu1d_), ModeratsArt, Cozomo, Krybharat and many others. What I appreciate most is their ability not only to appreciate art but also to have the conviction and guts to hold onto it through both good and bad times. All the individuals I've mentioned are remarkable collectors, and some of them are artists as well, which I find absolutely amazing.

KV: What has been your experience with the elitism associated with the art market, particularly in the realm of digital art? Do you believe the market for ‘grails’ is already well-developed?

JW: I must say it's quite well-developed. Many think NFTs are 'dead'. However, when you want to acquire a truly desired work such as a 'Lost Robbie' or one of XCOPY's top editions or 1/1s, you will have to pay Substantially, and there is no chance someone will 'dump it'. Also, the 'grail' buzzword is heavily overused. The number of artworks I personally perceive as grails is tiny and limited to only a few 'names' in the blockchain-based art space today.

KV: Where do you see the future of the digital art market heading?

JW: I believe the digital art market will eventually dwarf the traditional art market. However, this transformation won't happen overnight - it could take years, perhaps even more… The digital art space has its own masters and pioneers, figures who are pushing boundaries and redefining artistic expression. It's perfectly natural that it will take time for the broader world to recognize and appreciate their contributions.

KV: What are your top three pieces of advice for new collectors?

JW: Develop your own opinions. Aim to acquire pieces that are so rare and desirable that once you sell them, the opportunity to repurchase them is almost nonexistent. Acquire what you love and what is truly hard to obtain.

KV: What are your top three pieces of advice for artists?

JW: Sell only what you are proud of. Treat collectors as your ambassadors - there is a great power beneath each artwork held by an engaged collector. Be a collector of your own works.

***

Jediwolf on X: @randomcdog

Collection on Superrare: https://superrare.com/jediwolf

UnderTheGAN Collection: https://opensea.io/UnderTheGAN

The Art and Science of Alexander Mordvintsev

Alexander Mordvintsev is a researcher and artist based in Zurich, Switzerland. He is best known for creating the DeepDream algorithm, which was introduced in 2015 and marks a major milestone in AI image generation. DeepDream demonstrates how machines can assist in creating images that abstract reality in ways humans might not conceive on their own, offering a new way of seeing. It has since inspired a new wave of artists experimenting with AI. Apart from his significant contributions to this technology, Mordvintsev is also an active artist. In our article, we delve into both his invention and the beginning of his artistic journey. As we mark the 5th anniversary of our iconic “Automat und Mensch” exhibition, where we first showcased his creations, we are pleased to present a selection of his early pieces created before DeepDream was open-sourced (2015 July). These works, initially not offered for sale, are now available, providing collectors a rare chance to engage with an important moment in art and technology.

When Alexander was about six years old, father brought home an amazing thing: a computer and a bunch of books full of tiny programs that one could type in. Many of these programs displayed interesting geometric patterns on an old black-and-white TV that served as a monitor. That’s how Alex fell in love with computers and generative art. This was the beginning of an exciting journey full of meeting and learning about great people, discovering great ideas from the past, and observing recent developments. Simulations of emergent phenomena, when simple rules lead to complex and unpredictable behavior, were particularly exciting. Demoscene was another source of inspiration for Alexander and this interest culminated in the display of own work “The Flow” at an Assembly demo party in Helsinki in 2009. Soon after graduation from Saint Petersburg State University of Information Technologies, Mechanics, and Optics Mordvintsev got heavily interested in Computer Vision. The challenge of teaching computers a skill that is so easy for us and so difficult for them was very deeply fascinating. After joining Google in 2014 Alexander got introduced to a modern generation of neural networks, and they certainly exceeded his expectations on what computers are capable of. This opened a new chapter for Alexander, in which he spent several years trying to figure out what’s going on inside. DeepDream happened to be one of the experiments trying to answer that question that got world attention.

At the time, Google led the field in neural network research with figures like Geoffrey Hinton and Jeff Dean, who headed the teams behind the Google Brain in Mountain View. In Mordvintsev’s initial years at Google, he studied key research papers and experimented with pre-trained recognition systems. He took advantage of Google's policy, which encourages employees to dedicate twenty percent of their work time to personally inspired projects, to delve into reverse-engineering image-trained neural networks. His goal was to unravel and visualize the inner workings of these technologies.

By early 2015, he had achieved some visually interesting results, but the true breakthrough came unexpectedly late on the night of May 18. Awakened from a nightmare at 2:00 am, he was inspired to start an experiment. When the experiment finally succeeded, he immediately shared the results on a company social network and then returned to sleep. The following morning, he received numerous comments from his colleagues at Google who quickly recognized the significance of his work. This initial interest in DeepDream was just the beginning of what would soon become a viral phenomenon.

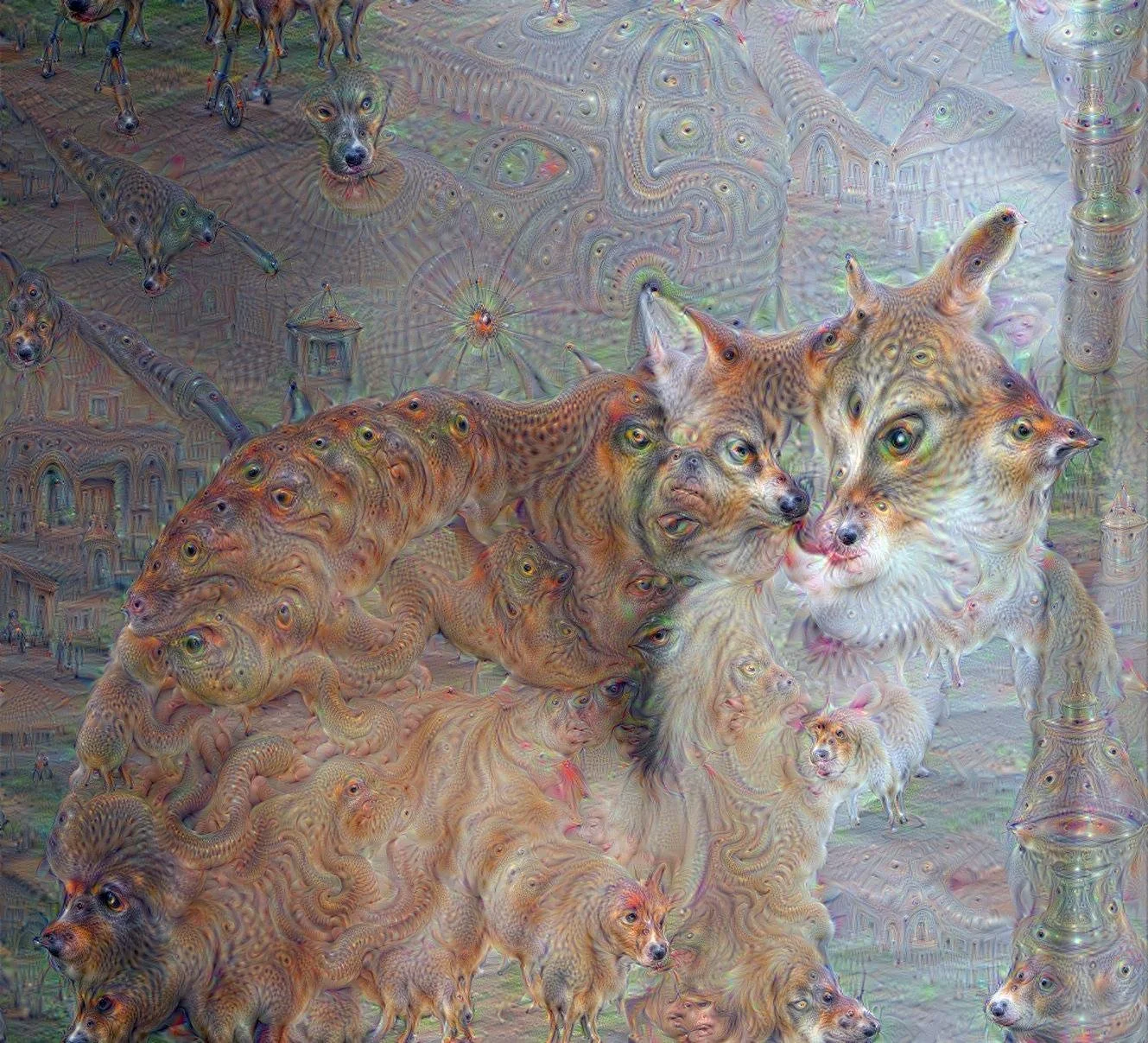

Alexander Mordvintsev, DeepDream is like looking at the clouds, 2015/05 (Not for sale)

Mordvintsev's innovation allowed the computer some autonomy to "dream", thus revealing the complex and often surreal workings of its data processing. His experiment reversed the standard image recognition process in convolutional neural networks (ConvNets), primarily used for vision. These networks usually process images layer by layer, each interpreting and refining the data to construct a final image from basic shapes to detailed recognitions. Mordvintsev interrupted this forward processing to manipulate the mid-layers, coaxing the network to enhance and generate features from partial data, resulting in bizarre, hybrid creations. This exploration of neural networks' "hidden layers" provided valuable insights into their operation. Mordvintsev's work suggested a parallel between the function of these neural networks and human perception, both capable of identifying shapes and patterns where none explicitly exist.

The final images that emerge from DeepDream are often characterized by intricate, hallucinogenic patterns and a dreamy, surreal aesthetic. Common visuals include enhanced textures and repetitive patterns, such as eyes or architectural forms, which emerge organically within the image. At the beginning, the system often created images that combined elements of dogs and cats into a fantastical creature. Mordvintsev utilized a pretrained neural network known as ImageNet, which has been a benchmark for image classification since its establishment around 2010. ImageNet is particularly noted for including 120 categories of dog breeds to demonstrate its capability for "fine-grained classification”. Due to this focus, there's a strong bias towards dog breeds in the dataset, which influences the results significantly. For one of his first experiments, he fed ImageNet a digital wallpaper image featuring a beagle and a kitten, each perched on tree stumps in a meadow. Interestingly, the output image was predominantly influenced by the dog category—despite the presence of the kitten in the image. This led to fragments of dog faces appearing in unexpected places throughout the image. The outcome was surreal, resembling something out of a hallucination, though its origins were not psychiatric or psychotropic but purely algorithmic.

Later, Mordvintsev published his work on DeepDream on Google’s public research blog, alongside his colleagues Christopher Olah, a software engineering intern, and Mike Tyka, a software engineer. The publication quickly captured the internet's attention. Within just a few days, the images were featured in over 100 articles, and spread across countless tweets and Facebook posts. The technology was made accessible to the public through a variety of apps and APIs, allowing anyone interested to create their own DeepDream images. This accessibility helped foster a thriving DeepDream community, significantly influencing public engagement with machine learning and computer vision. The impact of DeepDream extended beyond casual interest, inspiring some individuals to pursue PhDs in related fields and leading notable artists like Mario Klingemann to explore this technology and neural networks more broadly.

At that time, Mordvintsev didn’t view himself as an artist and considered these images to be merely byproducts of his research. However, in 2017, encouraged by his wife, he began to produce more art using DeepDream and eventually embraced the title of “artist” alongside his role as a research scientist. Since then, his art has been showcased worldwide in prestigious venues such as the Barbican Centre in London, Art Fair Zurich, and Gray Area in San Francisco, CA.

We are proud to have been among the first to exhibit his artworks in 2019 at our "Automat und Mensch" show, which highlighted the evolution of generative art from the 1960s to the present, featuring both pioneering and contemporary artists. At this exhibition, we displayed “Cats”, one of the first pieces he created using DeepDream in 2015. Initially, his works were not for sale. Now, as we celebrate the five-year anniversary of our landmark show, we are excited to present exclusive early works, giving collectors the opportunity to enrich their collections with these historically significant pieces.

Automat & Mensch 2.0 - 5 years milestone

“The romance of art and science has a long history, albeit a mixed one. Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), the artist and polymath active in the Florence of the Renaissance, still serves as the prominent example for the enormous creative potential flowing from the interactions of art and science.”

- Andreas J. Hirsch, The Practice of Art and Science – Experiences and Lessons from the European Digital Art and Science Network

As we walk into Kate Vass Galerie on this nostalgic May 29th, 2024, we feel like we're stepping back in time. It's been five years since the "Automat und Mensch" group exhibition fascinated everyone with its wide retrospective highlighting the history of AI and generative art in its attempt to cover 70 years of history in one location. Now, as we look back on this important milestone, we're taking a journey through how AI and generative art have changed since 2019, with both old favorites as our guides.

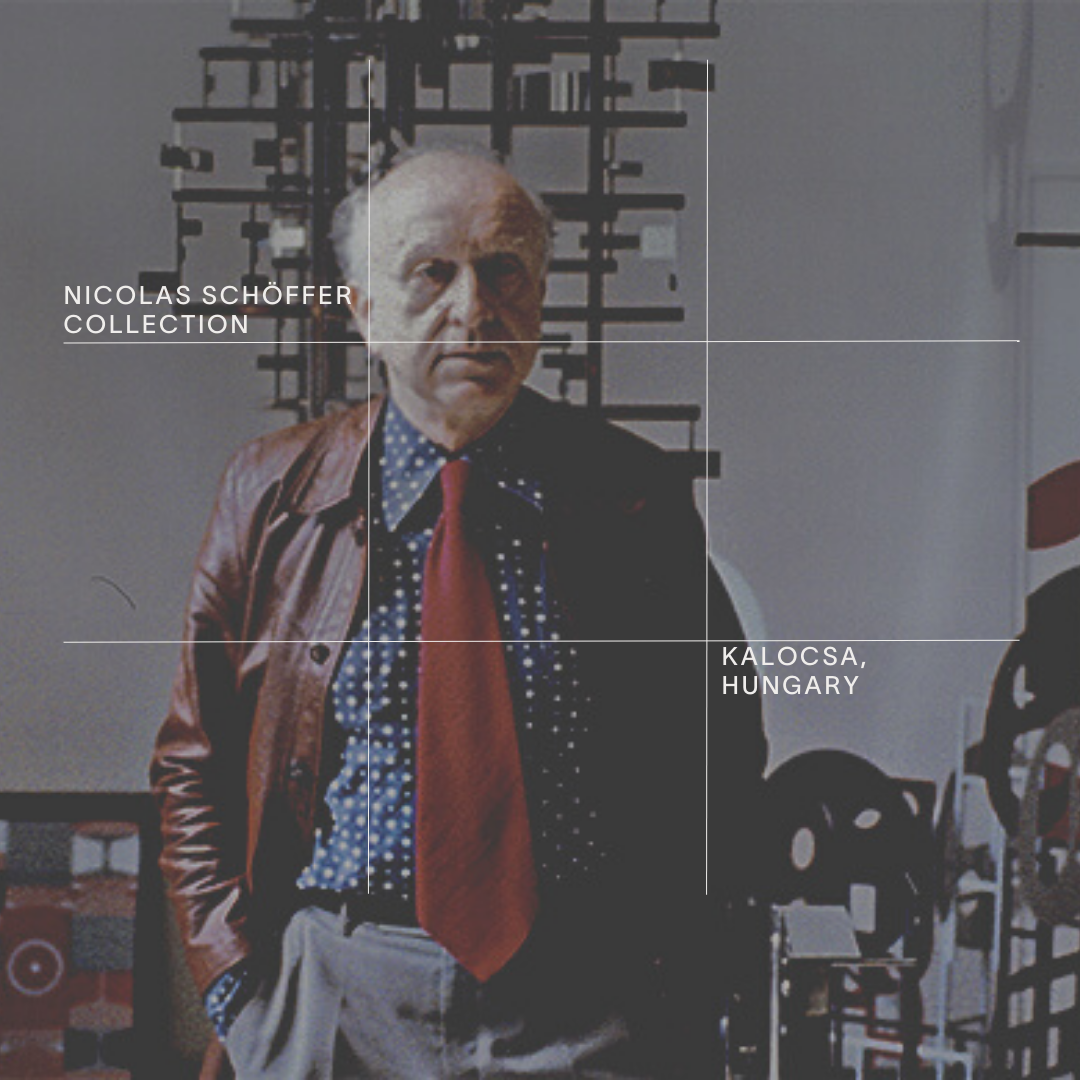

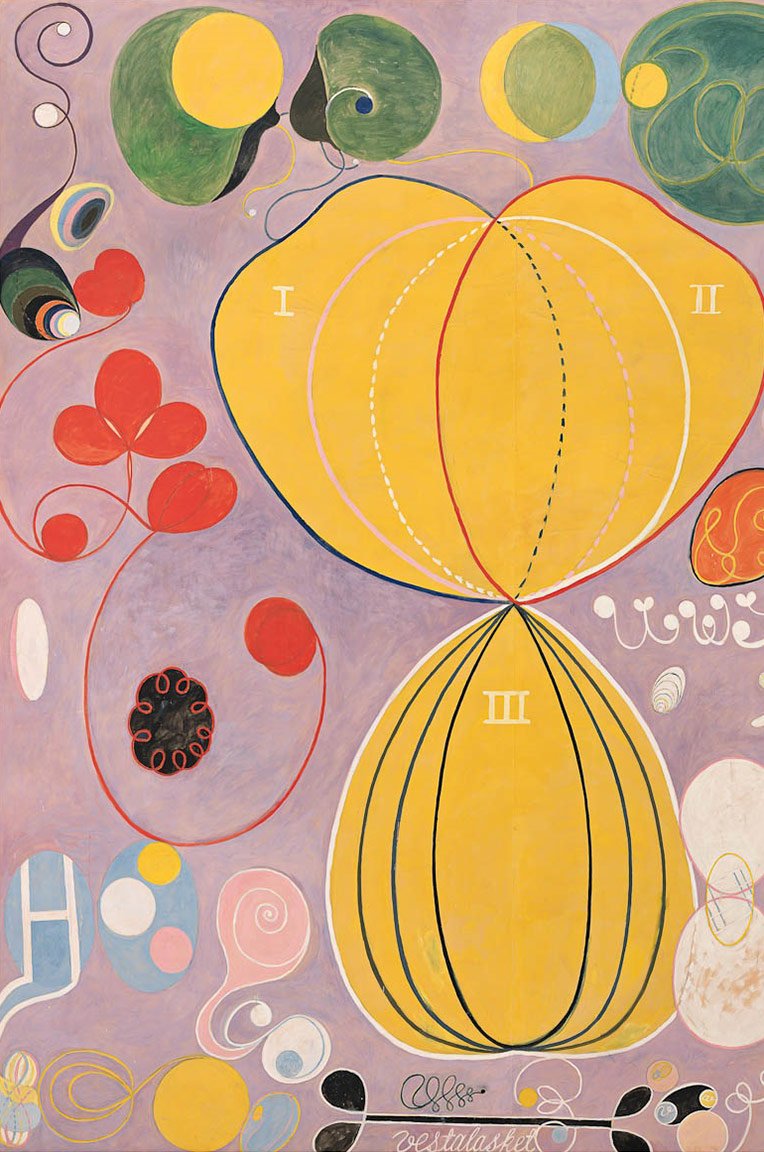

The exhibition, titled "Automat und Mensch", was curated with precision and foresight, showcasing a captivating mix of artworks by pioneering artists such as Nicolas Schöffer, Herbert W. Franke (still alive at the age of 91), Frieder Nake, Vera Molnar (still alive at the age of 95), Roman Verostko, Manfred Mohr, Gottfried Jäger, Harold Cohen, Benjamin Heidersberger, Cornelia Sollfrank, and Gottfried Honegger.

The show featured several generative works from the early 1990s by John Maeda, Casey Reas, and Jared S. Tarbell. Works by Matt Hall and John Watkinson, Harm van den Dorpel, Primavera de Filippi and Manoloide were also on display to represent the contemporary scene.

While the show’s focus was on the historical works, taking the name from the eponymous book by K. Steinbuch “Automat und Mensch” that inspired many generative art pioneers from the 60s, the shows also highlighted the wide range of important works by living AI artists like Robbie Barrat, Mario Klingemann, Alex Mordvintsev, Tom White, Helena Sarin, David Young, Kevin Abosch, Sofia Crespo, Memo Akten and Anna Ridler, whose groundbreaking practice has influenced many emerging artists since 2019.

As we journey five years back in time to revisit the show, our aim is to reflect upon the trajectory of AI in art and the evolution of generative art over the past half-decade. We explore the transformative impact of technological advancements, paying homage to pioneering artists who laid the groundwork, while also highlighting new artworks.

The Evolution of AI and Generative Art in a Historical Context.

From the intricate patterns of Manoloide's "Mantel Blue" to the surreal visions of Alex Mordvintsev's "DeepDream" experiments, the generative art scene has been defined by visionary artists expanding the limits of computational creativity for decades. While the fluid, organic imagery marks a shift from geometric abstraction, AI art is a subset of generative art, despite some disagreement that we have heard in recent months. Therefore, knowing the history of evolution is so important.

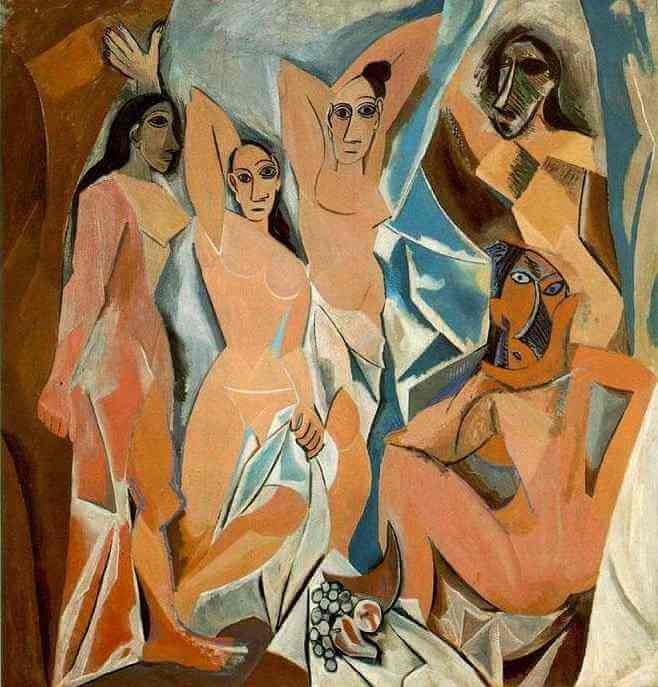

The commonly told story of AI art history often begins with Harold Cohen's pioneering work and then moves through the development of GANs and DeepDream, but this narrative overlooks several important early chapters. The “Automat und Mensch” exhibition aimed to highlight some parts of generative art history, showcasing the work of mid-20th century artists like Frieder Nake, Vera Molnár, Herbert W. Franke, Georg Nees, Gottfried Jäger, and others, who experimented with algorithmic art long before AI techniques became prominent.

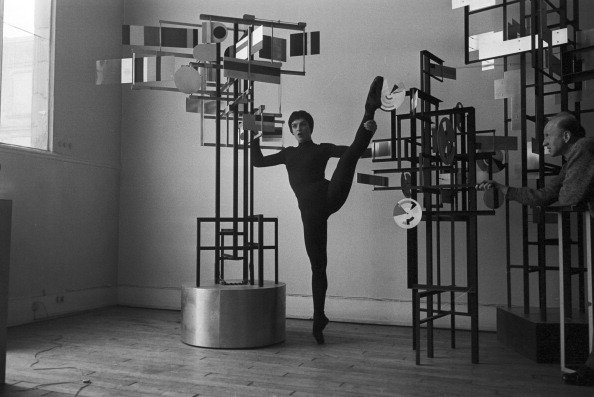

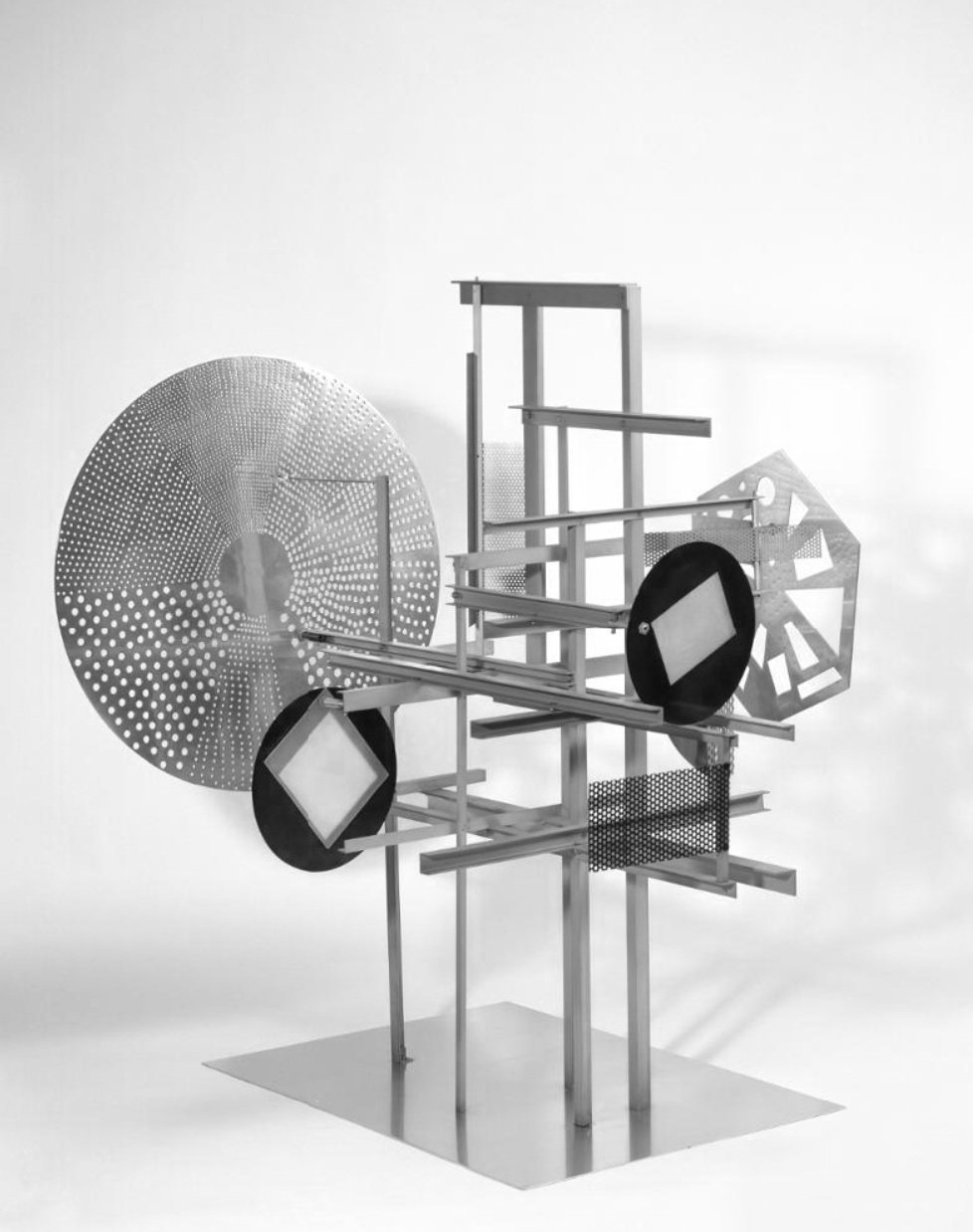

Nicolas Schöffer, a pioneering figure, significantly impacted these developments with his works in cybernetic and kinetic art during the 1950s. Drawing inspiration from Norbert Wiener's cybernetic theories of control and feedback, Schöffer conceptualized an artistic process rich with feedback loops, circular causality, and a fundamental emphasis on movement. He created moving, illuminating sculptures and installations that emitted sounds in collaboration with engineers, architects, composers, and dancers. In his “Chronos” series, he designed these sculptures to be characterized by their responsiveness to external stimuli such as light, traffic noise, and ambient sounds, which actively influenced the movement and behavior of the works. Schöffer’s unique approach melded art, technology, and science. His work embodied the foundational principles of generative art by engaging dynamic systems to produce art, and his mechanical systems in artworks forecasted the later use of autonomous systems in art creation.

The 1960s were characterized by a fascination with technology and instant communication, prompting artists to experiment with electronic feedback using new video gear. Pioneers like Steina and Woody Vasulka played with different sounds and visuals. They were joined by others, like Edward Ihnatowicz, Wen Ying-Tsai, Gordon Pask, Robert Breer, and Jean Tinguely, who mixed biology with technology in their art. At the same time, cyborg art became popular, exploring the relationship between humans and machines. Writers like Jonathan Benthall, Gene Youngblood, and William Gibson introduced the term "Cyberpunk”. British artist Roy Ascott and American critic Jack Burnham also developed significant theories on the integration of art and life.

“In conceptual art, the idea is not only starting point and motivation for the material work, it is often considered the work itself. In algorithmic art, thinking the process of generating the image as one instance of an entire class of images becomes the decisive kernel of the creative work.” - Frieder Nake

With the rapid advancement of computer technology and the influence of Max Bense's information theory artists began leveraging autonomous systems such as computer programs and algorithms for artistic expression. During this period, artists often collaborated with scientists due to the limited availability of computers, which were primarily located in universities, research institutions, or large corporations. Pioneers of this movement, including Frieder Nake, Georg Nees, Vera Molnár, and Manfred Mohr, utilized computational processes to explore new aesthetic territories, each demonstrating the potential for machines to contribute to the creative process. Parallel to the rise of generative art, generative photography emerged, drawing from the experimental photography of the 1920s and concrete photography of the 1950s. This technique involves the systematic creation of visual aesthetics through predefined programs that perform photochemical, photo-optical, or photo-technical operations, merging traditional photographic methods with mathematical algorithms. The first exhibition to showcase these works took place at Kunsthalle Bielefeld in 1968, featuring artists like Hein Gravenhorst and Gottfried Jäger.

While these artists laid the foundation for computer-generated art, Harold Cohen was the first artist to introduce AI into art with AARON, a software considered one of the first AI art systems, which he began developing in the early 1970s. AARON used a series of rules defined by Cohen to autonomously generate images. This allowed the program to independently make decisions about composition. Cohen's software evolved from producing abstract monochrome line drawings, which he initially colored by hand, to creating more complex, colorful, and even representational forms with drawing and painting devices that he engineered.

The development of AI experienced notable fluctuations in progress, leading to periods known as AI winters. The first significant AI winter occurred in the 1970s, prompted by disillusionment due to overhyped expectations and resulting in substantial cuts in funding and critique of the technology. A similar downturn happened again in the late 1980s, marking another AI winter. This second period of stagnation was primarily due to the limitations of the AI technologies of the time and the constraints imposed by the available hardware. Despite these setbacks, interest in AI did not completely vanish. Instead, it veered in new directions as academic researchers and artists found alternative applications and methodologies for the technology.

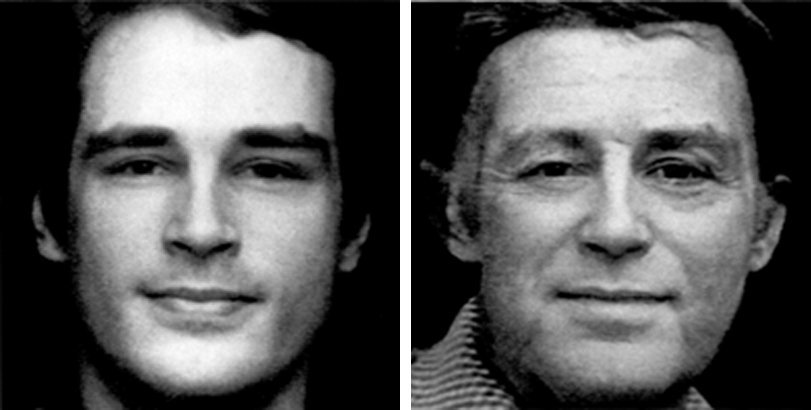

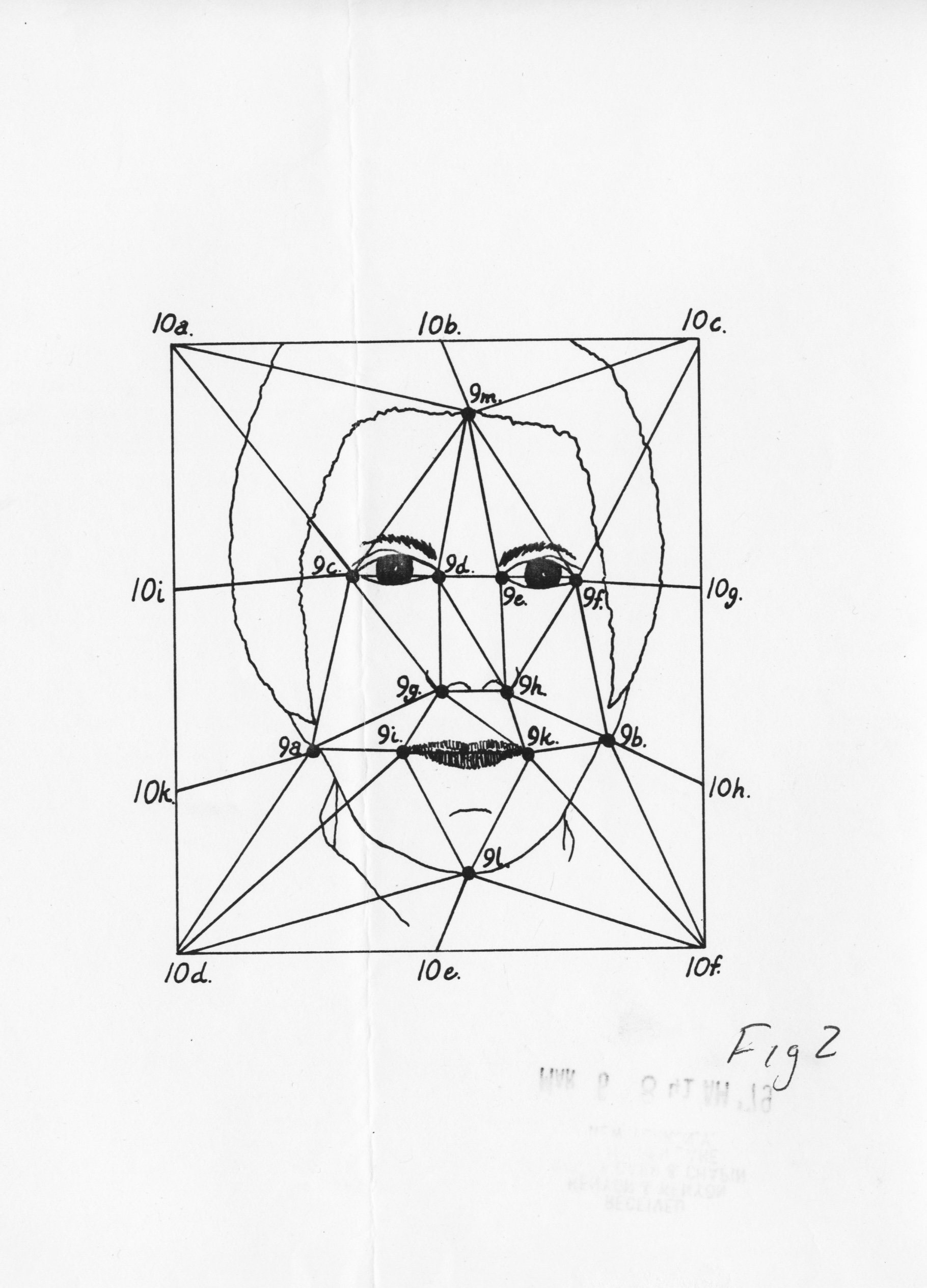

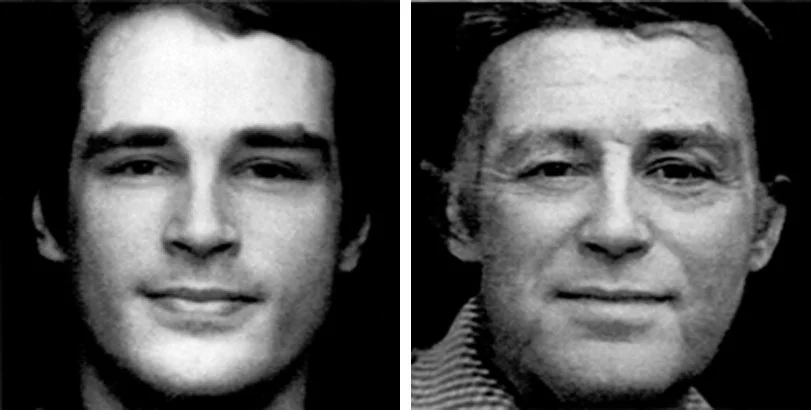

Nancy Burson, a pioneering artist from the early 1980s, is often overlooked despite her significant contributions to the intersection of art and technology. She is best known for her innovative work in computer morphing technology and is considered the first artist to apply digital technology to the genre of photographic portraiture. Burson’s creations are widely recognizable, even by those unfamiliar with her name. Some of her most notable works include the digitally morphed “Trump/Putin” cover for Time magazine. Burson developed her morphing software in 1981, known as “The Method and Apparatus for Producing an Image of a Person’s Face at a Different Age”, while she was at MIT. This technology was used in her interactive installation, the “Age machine”, which simulates the aging process and offers viewers a glimpse of their future appearance. Through her cutting-edge work, Nancy Burson explores questions about identity and aging, highlighting social, political, and cultural issues, and focusing on societal biases and injustices. Her works will be exhibited at LACMA this year, continuing to underscore her role in shaping how technology is used in artistic practices.

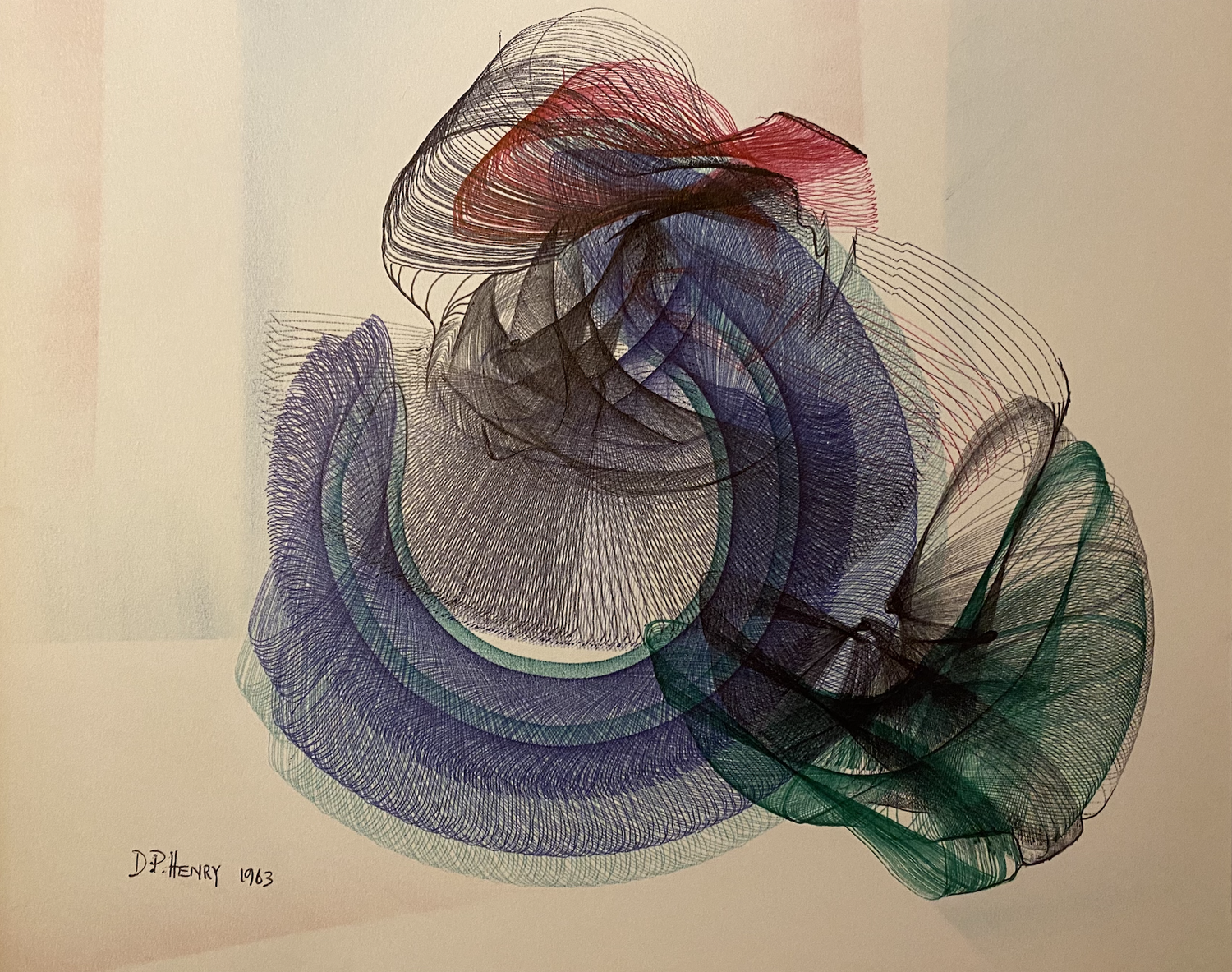

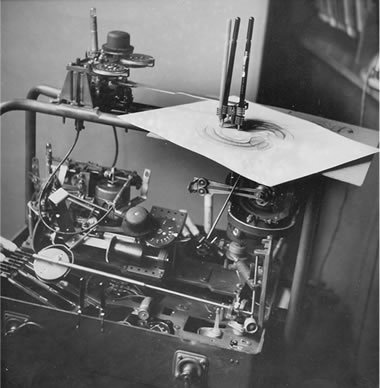

We must also highlight Roman Verostko, another pioneering generative artist from the 1980s. In 1982, he developed "The Hand of Chance", an interactive generative art program that executed his art ideas on a large PC monitor. Later, Verostko's interest shifted toward printed versions of his works. By the late 1980s, he had developed a program that controlled the drawing arm of a pen plotter, enabling it to create intricate and complex drawings that were unprecedented at the time. Using this drawing arm, Verostko was one of the first artists to incorporate brushwork in his computer-generated drawings. He named his software Hodos, which means "path" in Greek, a reference to the methodical way the strokes follow paths determined by the underlying chaotic system. Using this tool, he created several series, such as "Pathway", an exploration of abstract forms plotted by a multi-pen plotter driven by his software. We are excited to feature a few of his early works from the 1980s in this article.

By the 1990s, cybernetics had become firmly entrenched in the industrial landscape of the Western world. Advancements in technology brought about new terminology and interpretations, rendering some fundamental cybernetic concepts outdated. Nonetheless, it would have been beneficial for the “Automat und Mensch” exhibition to showcase artworks and narratives that acknowledge the broader societal and cultural contexts in which AI art has developed. For instance, consider the early pioneer of AI art, Lynn Hershman Leeson, whose interactive installation "Shadow Stalker" (2018–21) employs algorithms, performance, and projections to highlight the biases inherent in private systems like predictive policing, increasingly utilized by law enforcement or “Agent Ruby”, a female chatbot whose mood could be influenced by Web traffic day.

From the conceptual reflections of early AI pioneers to the practical applications of machine learning algorithms, the relationship between AI and art has undergone a remarkable evolution. It started in a lively and experimental environment, where artists and technologists went on a journey to discover the hidden possibilities of computer creativity which led to a mass adaption of open-source AI models, Chats, and generative art by 2024.

“The shift from a mechanical to an information society demands new communication processes, new visual and verbal languages, and new relationships of education, practice, and production.” – Muriel Cooper, Director MIT Press, Founder MIT’s Visual Language Workshop from 1975 (MIT LAB later from 1985).

Casey Reas, Ben Fry, Jared S. Tarbell & Manoloide.

What all the above names have in common?

“I have ideas about how software tools can be improved for myself and communities of other creators. I want to be a part of creating a future that I have experienced only in fits and starts in the recent past and present. I have seen independent creators build local and networked communities to share intellectual resources and tools.” - Casey Reas

The rapid development of computer technology in the late 20th century provided artists with new tools and capabilities to explore complex systems and patterns, creating artworks that reflected intricate interactions between programmed logic and random elements. The introduction of Processing in the early 2000s marked a pivotal moment, revolutionizing the production and proliferation of generative art.

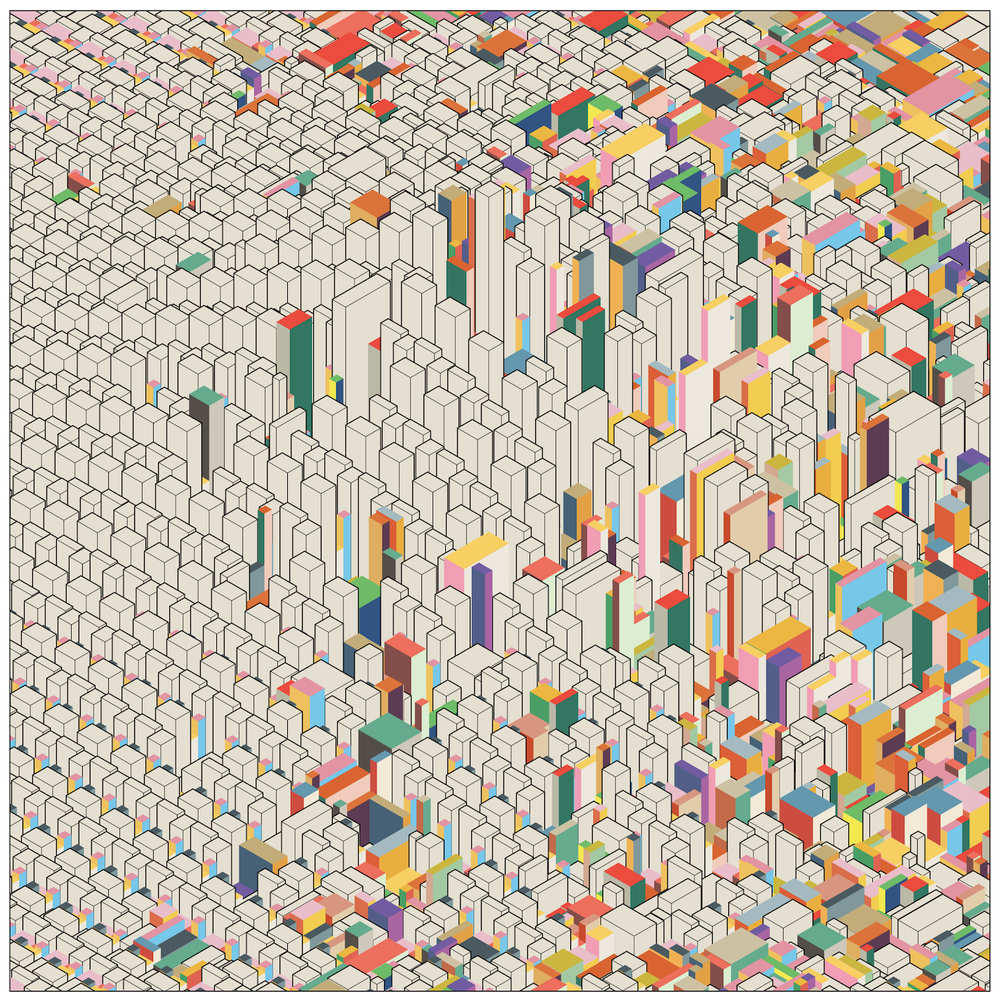

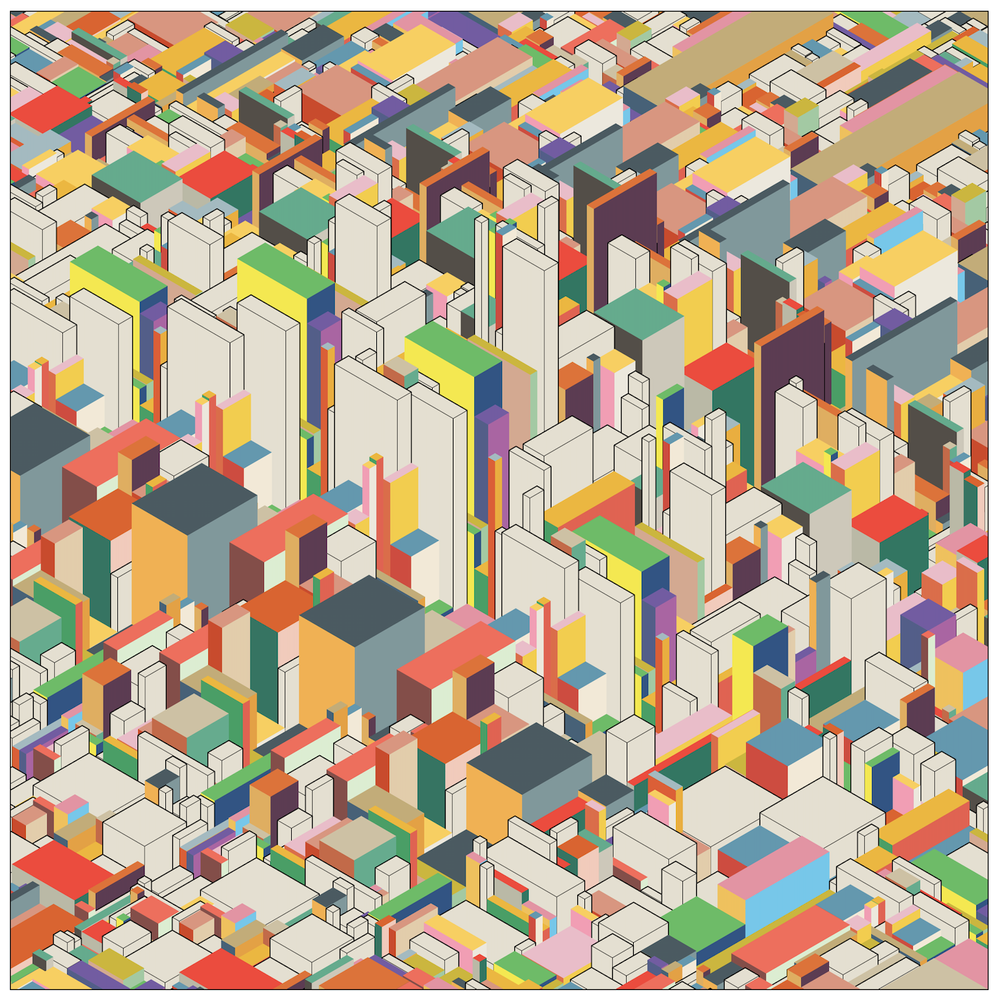

Founded by Ben Fry and Casey Reas in the spring of 2001, Processing democratized the creation of generative art, making it accessible to anyone with a computer. In 2012, they, along with Dan Shiffman, established the Processing Foundation. This platform eliminated the need for expensive hardware and extensive programming knowledge, enabling more people to create art through code. Processing is an example of a free, open, and modular software system with a focus on collaboration and community. Processing's influence on an entire generation of artists and programmers is immense, transforming data visualization and generative art. In 2003, Jared S. Tarbell began using Processing to create engaging generative artworks that stood out both conceptually and visually. One of his most iconic works, "Substrate", showcases the brilliance of a simple algorithm: lines grow in a specific direction until they reach the domain's boundary or collide with another line.

When a line stops, it spawns at least one new line perpendicular to it at an arbitrary position. Recreating the city-like structures of "Substrate" is a fascinating exercise. From Tarbell, we can learn three key things: the value of the algorithms he shared, an artistic and exploratory approach to uncovering possibilities in code, and that profound and unexpected results can emerge from following simple rules. We are excited to showcase Substrate Subcenter2024 by Jared S. Tarbell at Kate Vass Galerie.

“A line is a do that goes for a walk” - Autoglyths by John Watkinson & Matt Hall, kleee02 by Johannes Gees & Kelian Maissen.

The introduction of blockchain technology and the founding of Ethereum in 2017 marked another revolutionary shift, impacting not only generative and AI art but also transforming the traditional art market, unleashing the power of community to drive creativity in unprecedented ways.

One of the most iconic projects, “Autoglyphs” by John Watkinson and Matt Hall, debuted at the “Automat und Mensch” show in 2019. As fine art works, “Autoglyphs” are now celebrated as the first on-chain generative art on the Ethereum blockchain. This collection of 512 unique outputs has become a highly coveted set for generative art collectors. Matt and John, enthusiasts of early generative art, have drawn inspiration from the 1960s aesthetic and experimented with the computing and storage challenges faced by pioneers like Michael Noll and Ken Knowlton. Their work reflects a deep respect for the origins of generative art while pushing its boundaries.

Ken Knowlton, from the pages of Design Quarterly 66/67, Bell Telephone Labs computer graphics research

Another lesser-known project, “kleee02”, was launched around the same time in Switzerland. It was an unfortunate oversight not to include it in our show. “kleee02”, an art piece by Kelian Maissen and Johannes Gees, had its smart contract verified in April 2019, the same week as “Autoglyphs”. This work offers a contemporary, blockchain-inspired take on conceptual art, inspired by Swiss artist Paul Klee’s famous quote, “A line is a dot that goes for a walk”. The "walk of the dot" is detailed in the “kleee02” smart contract, with each of the 360 non-fungible tokens (NFTs) being unique in shape and color. Uploaded to the Ethereum blockchain on April 10, 2019, “kleee02” emerged as a pioneering project that could have been featured in the "Automat und Mensch" show in May 2019. The project was officially launched on June 3, 2019, with a public laser projection of the first minted NFTs at Johannes’s studio in a park near Zurich, Switzerland.

Since then, the adoption of blockchain, the launch of ArtBlocks in November 2020, and the foundation of so-called “long-form generative” art have transformed the entire landscape of ownership and value. These innovations have enabled the community to better understand and collect generative art as NFTs, fostering a new era of digital creativity for the next five years.

Alex Mordvintsev, Robbie Barrat, Mario Klingemann, and Helena Sarin.

The past five years have witnessed a dramatic leap in AI capabilities, ushering in an era of unprecedented innovation in artistic expression. Deep learning algorithms, Mid Journey, Stable Diffusion, Dall-E, ChatGPT and other open-source models have revolutionized the creative process, enabling artists to transcend traditional boundaries and explore new frontiers of imagination. Nevertheless, we see a set of trends that after the spike of newer tools, the attention of collectors returns to the earlier AI generation, predominantly GANs (generative adversarial networks) artworks, concept based on neural networks that computer scientist Ian Goodfellow introduced in 2014. The greatest attention is also given to contemporary early AI creators such as Mario Klingemann, Robbie Barrat, David Young, Gene Kogan, Memo Akten, Helena Sarin and more, who have been working with AI for decades.

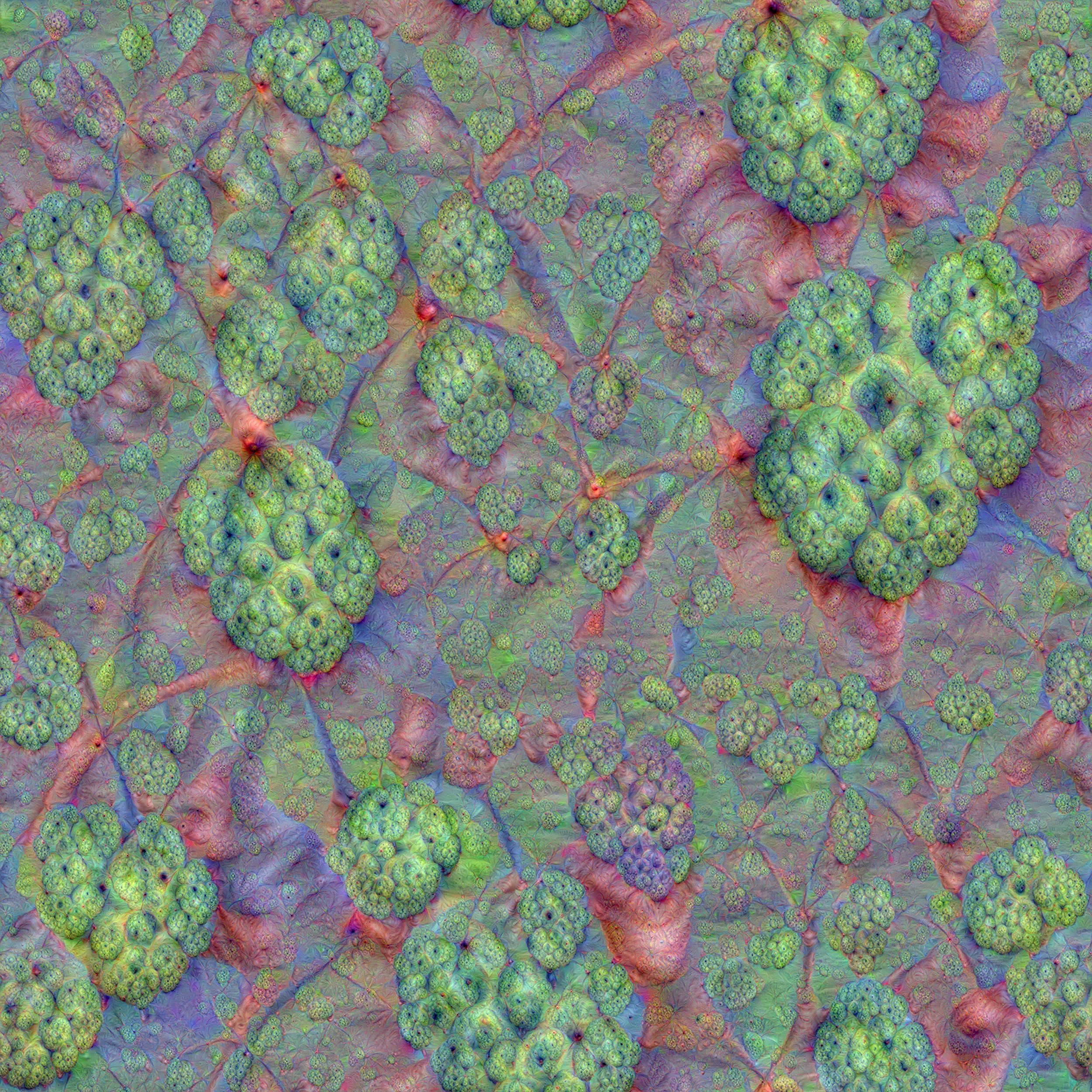

Alexander Mordvintsev, Custard Apple, 2015

Alexander Mordvintsev, Whatever you see there, make more of it!, 2015

One of the earliest and most influential works in this field was created by Alexander Mordvintsev, the inventor of Google DeepDream. Released as open source only in July 2015, DeepDream mesmerized audiences with its psychedelic and surreal imagery. Nearly all contemporary AI artists attribute Mordvintsev's DeepDream as a major source of inspiration for their exploration of machine learning in art. While one of the initial images generated by DeepDream was showcased at the 2019 “Automat und Mensch” exhibition, it was not offered for sale and was displayed as a small physical print.

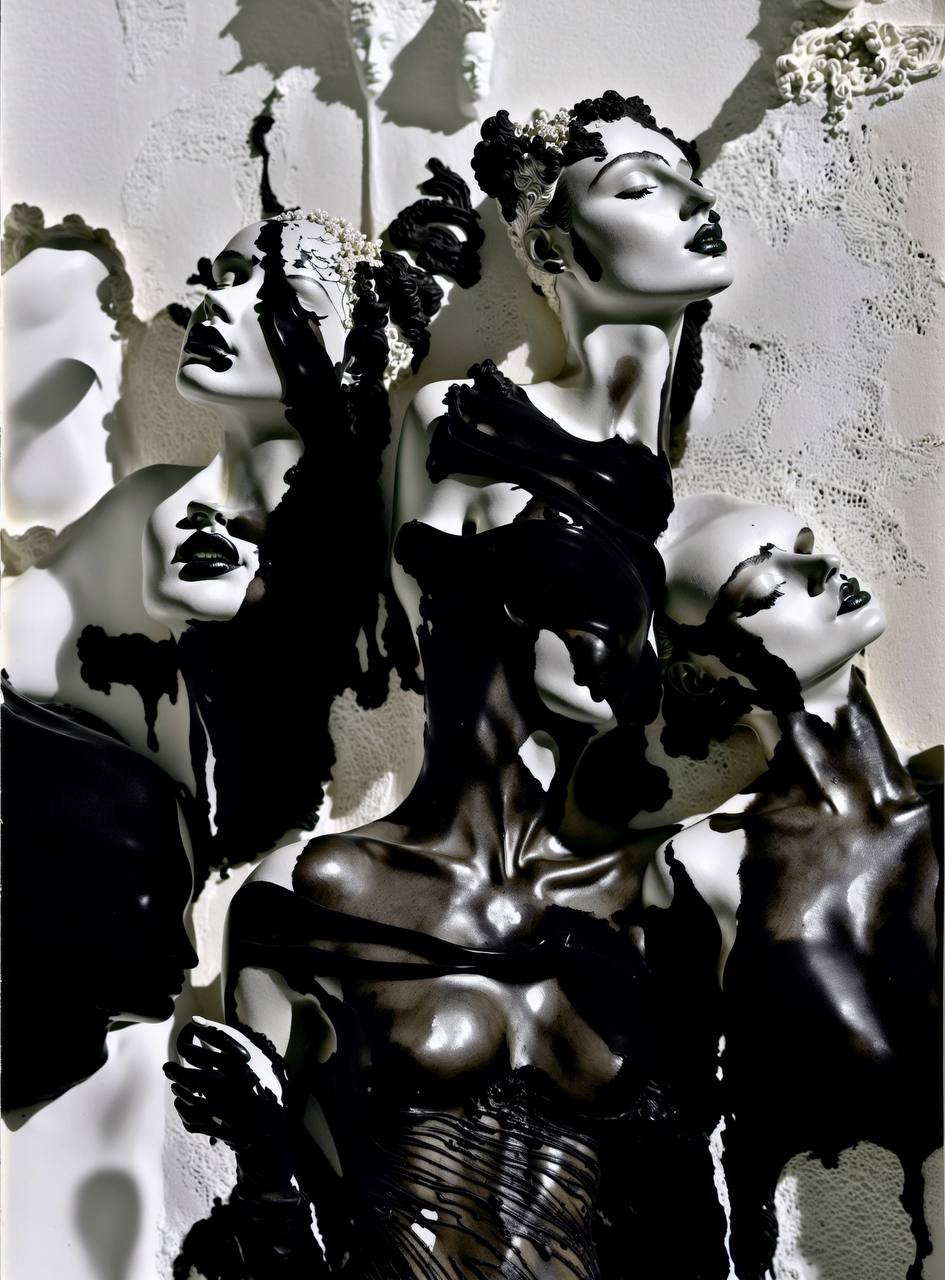

After DeepDream, many artists began experimenting with incorporating AI technologies, particularly machine learning and neural networks, into their art. One such artist, Robbie Barrat, created works like “Correction after Peter Paul Rubens, Saturn Devouring his Son” (2019), which have gained increased significance from a historical perspective. Robbie Barrat, who was just 19 in 2019, displayed various artworks at “Automat und Mensch”. This piece exemplifies how technology can be harnessed for creative exploration, showcasing the potential of AI in art. Since 2018, Robbie has been collaborating with French painter Ronan Barrot, exploring AI as an artistic tool. "Correction after Peter Paul Rubens, Saturn Devouring his Son" is influenced by Ronan's technique of covering and repainting unsatisfactory parts of his work. Robbie applied this concept to AI by teaching a neural network to repeatedly obscure and reconstruct areas of nude portraits. This process, known as inpainting, aligns the painting with the AI's internal representation, often resulting in a completely transformed image. The term "correction" here reveals the AI's interpretation of the nude body, not an attempt to improve the original works.

In another notable project, "Neural Network Balenciaga”, Robbie Barrat used fashion images to train his AI model. In a 2019 interview with Jason Bailey, Barrat explained that he combined Pix2Pix technology with DensePose to map the new AI-generated outfits onto models, crediting another established artist, Mario Klingemann, for developing the DensePose + Pix2Pix method.

Mario Klingemann, who won the Lumen Prize in 2018 and had his work auctioned at Sotheby’s in 2019, was one of the known artists featured in the show for his work “Butcher's Son”. Mario continues to produce visually fresh and refined art, experimenting with different technologies, whether using GANs or other tools. His unique artistic style is consistent, recognizable, conceptual, and experimental.

As AI technology becomes more widely accessible, the distinction between exceptional AI artists and those who merely repurpose old work or simplify image creation by pushing the button relies increasingly on vision, fresh ideas, and later innovation. Helena Sarin, for instance, one of the key figures in the AI scene, has maintained her unique style and tools over the last five years, creating art, books and pottery that stand out stylistically among the rest. Her practice underscores the significance of artistry and dedication to the original creativity. Helena Sarin's ethereal compositions, infused with a sense of wonder and mystery, continue to captivate audiences with their poetic resonance. “They don’t do GANs like this anymore” captures the essence of today’s AI art scene.

Conclusion

While there is a current upswing in interest in AI art, it's difficult to predict whether this trend will continue or if a correction is on the horizon. Nonetheless, digital art undeniably holds a significant and dynamic position in the contemporary art landscape.

Debates about whether AI will dominate the world or if human creativity will diminish in the coming decades are pressing questions of our time. Since the term "artificial intelligence" was coined in the 1950s at the Dartmouth conference, the pursuit of creating artificial general intelligence has been ongoing. Despite this, the concept of "intelligence" remains elusive. Algorithms, while capable of operating independently, do not match the general intelligence of the human mind.

AI saw significant progress with early systems like ELIZA up until the late 1970s. However, by the early 1980s, interest and funding began to wane, contributing to periods commonly referred to as the AI winters. AI winter reflects a general decline in enthusiasm that paralleled cultural milestones like the release of the original “Blade Runner” in 1982.

Could another AI winter follow the current surge of interest, since we have similar trends in 2020s with multiple wars, economic distress, and world political instability? Initially, technology was intended to support and extend liberal democracy after the Cold War. However, recent developments suggest it might be on the brink of instigating a new era of conflict.

The relationship between human and artificial intelligence might cool for various reasons. If the clash between human and artificial intellect collapses into neglect, another AI winter could ensue. Alternatively, the substantial financial and human investment in AI thus far could lead to a prolonged struggle, potentially triggering a "cold war" with intelligent algorithms too, couldn’t it?

Art, however, has proven to endure and evolve over the past 80 years. We believe that in the next 80 years, some current pioneers will be recognized as cultural icons in the history of generative and AI art. As life progresses, we innovate, trends change, and artists continue to create. Despite these advancements, we have yet to develop “general superintelligence” capable of creating independently from human influence and input.

Le Random has released an exclusive interview with Jason Bailey, Georg Bak, and Kate Vass to highlight the show on its 5th anniversary. Read the full article by clicking the button below.

Op-Ed: We Must Decode the Past to See the Future of Digital Art

Cryptopunk #795, 2018 by Larva Labs, John Watkinson & Matt Hall

In the ever-evolving landscape of the art industry, looking to history can often provide valuable insights into contemporary trends and future trajectories. Much like the familiar headlines of the 1980s, our current era resonates with economic and political instability, technological innovations, and shifting market dynamics.

While society faces with uncertainties of past decades, the art market undergoes its own metamorphosis, driven by innovation and adaptation. Like the trailblazing figures of the past, young collectors challenge traditional paradigms and spearhead new trends, reshaping the dynamics of art acquisition and appreciation. We shift more towards a digital culture, AI post-reality, and social media’s influence in gathering global investments.

The emergence of NFTs and memecoin culture serves as a testament to this ongoing evolution, representing social changes and the democratization of art. This shift parallels the advent of web3 digital culture and the rise of AI to mass adoption, which have democratized creativity and transformed how we engage with art, collecting, and value in general.

We can gain valuable insights into the societal, cultural, and economic forces that have shaped significant art movements throughout history. From the Middle Ages and the Renaissance to the digital era, the trajectory of art reflects broader societal shifts and showcases the democratization of art.

Duccio di Buoninsegna, Maestà, 1308–1311, Source: wga.hu

Bronzino, Portrait of Cosimo I de' Medici, 1545, Source: museothyssen.org

In ancient times, art was primarily commissioned by rulers and religious institutions for personal enjoyment, ceremonial purposes, or as a symbol of power. During the Middle Ages, the Christian Church emerged as the principal patron, financing artworks that communicated spiritual themes and teachings. The Renaissance introduced a significant shift as wealthy merchants began to compete with the aristocracy in commissioning secular art. Notable patrons like the Medici family directly supported artists, transforming art collection into an emblem of wealth, education, and refined taste.

From the 19th century, the wealth generated by industrialization introduced a new class of art collectors, democratizing access to art by moving beyond the traditional aristocracy. Collectors like Gertrude Stein, Paul Durand-Ruel, and Peggy Guggenheim played pivotal roles in supporting and legitimizing new artists and movements. Their efforts helped broaden the art market and elevate the significance of private collectors in promoting genres. The post-war period further democratized art through the establishment of fairs and biennales, making art more accessible to a wider audience. During this time, Leo Castelli’s innovative gallery model offered financial and creative support to artists, allowing them to pursue their work free from immediate market pressures, thereby contributing to a more inclusive and diverse industry.

Throughout history, the evolution of art has not only mirrored the democratization of our society but also reflected societal changes, with art acting as a barometer for prevailing ideologies and cultural shifts. Art has transitioned from primarily serving religious and royal propaganda to embodying the humanistic and individualistic spirit of the Renaissance and, later, the social dynamics of the Industrial Revolution. Entering the second half of the 20th century, in the 1980s, the art world favored “bold, cheeky, tough” works influenced by societal trends. However, events like the 1987 stock market crash and the AIDS crisis profoundly impacted the art scene. By the late ’90s and 2000s, with increasing global wealth, there was a surge in demand for artworks symbolizing success.

Interior of Gertrude Stein’s Studio in Paris, Source: tatler.com

Peggy Guggenheim, Source: vogue.com

The rise of NFTs in 2020 was driven by COVID-19, political and economic turbulences, the volatility of stock markets, and a drop in negative oil prices and bitcoin appreciation. These events have culminated in the current landscape of meme coin culture in 2024. However, the recent social reaction to the memes brought a lot of criticism.

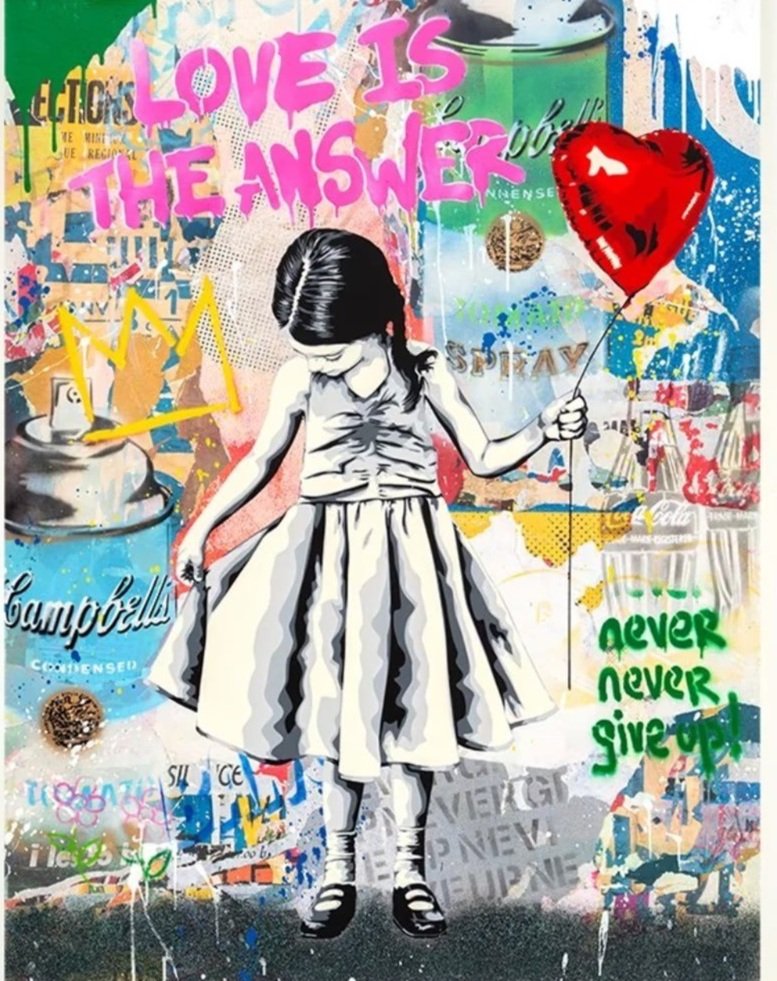

Consider the staggering performance of “street art” from the ’80s compared to ‘classical art’ over the past three decades. Interviews from the 80s reveal that neither auction houses nor prominent collectors showed much interest in collecting or selling this type of ‘contemporary’ art at that time when the ‘street artists’ had just begun. Street art was not taken seriously. It’s remarkable to observe how the industry’s focus shifted towards artists emerging from graffiti and vinyl toys. Leading top sellers like Banksy or Mr. Brainwash.

As you can see from the past, this transformative era challenges traditional notions of value and investment, potentially leading some to reflect on it from a different perspective, with varying senses of absurdity, including those within the legal system.

Like street art, memecoins and meme art should not be underestimated. The new generation represents the pivotal moment where digital art and meme cultures are interested in reshaping the financial and art landscape. In the future, meme coins have a great chance to stand as a culturally significant phenomenon, embodying the distinctive fusion of internet culture, financial speculation, and community-driven movements characteristic of the early 21st century. Over time, it will be recognized as a transformative period where humor and social media wielded power to disrupt traditional concepts of value and investment.

The present state of memecoins mirrors the evolving cultural landscape and underscores the impact of societal shifts, technological progress, and evolving consumer preferences on markets. Eventually, the legal system may adapt to regulate both traditional art markets and NFTs, with meme culture potentially serving as a catalyst for such changes.

Banksy Love is in the Air, Source: sothebys.com

Mr Brainwash, Beautiful Girl, Source: clarendonfineart.com

Nevertheless, as an audience and consumer base, we should take responsibility for our interests and behaviors that drive the demand for such digital assets. This phenomenon underscores the interconnectedness of culture, technology, and economics, highlighting our collective actions and preferences’ significant role in shaping market dynamics over time.

In the current moment, it’s crucial to acknowledge life’s inherent unpredictability and the evolution of taste. Instead of solely critiquing, we should embrace emerging tendencies and take action either to change or play along. The fortunate individuals are not those who merely recognize and foresee potential but those who actively engage and act.

CYBERFEMINISM

VNS Matrix, Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century, 1991. Source: vnsmatrix.net

Cyberfeminism emerged in the early 1990s, right after the arrival of the internet. The concept isn’t easy to describe with a single definition. It represents an international group of female thinkers, coders and media artists who are all interested in theorizing, critiquing, exploring and re-making the Internet, cyberspace and new-media technologies, which are free from social constructs.

The approach grew from the roots of third-wave feminism, which itself built on the foundation of earlier feminist movements. These earlier movements focused on issues like fighting for women's suffrage and equal rights. Cyberfeminism takes this fight into the digital age. Before the term, feminist analyses of technology often highlighted its social and cultural construction, noting its categorization as a masculine field. Despite women's significant contributions to technology, such as in computing, their roles were frequently marginalized or overlooked. Cyberfeminism emerged to challenge these narratives, questioning if technology could be a tool to hack patriarchy.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, CyberRoberta, 1996, Source: altmansiegel.com

The inspiration behind the movement is an essay published in 1985 by Donna Haraway, a post-humanist scholar and feminist theorist, “A Cyborg Manifesto”. The work explores the concept of the cyborg—a hybrid of machine and organism—as a figure that transcends traditional boundaries of gender, race, and even the distinction between natural and artificial. Haraway suggests that cyborgs, by existing outside of these dichotomies, can challenge established norms and hierarchies, including gender. The essay envisions a future that offers possibilities for overcoming biological determinism and promoting androgyny as an ideal.

In the 90s the term, cyberfeminism was independently coined in two different places by British cultural theorist Sadie Plant and the Australian artist group VNS Matrix. VNS Matrix, a collective of four women from South Australia, began their work in 1991. Their projects combined art with French feminist theory to address the male-dominated early internet. Inspired by Haraway’s writing, they published their "Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century" which was an aggressive statement against traditional norms, displayed as an 18-foot billboard with 3D images and provocative text. They also created "All New Gen", an arcade game that criticized sexism in pornography and video games by depicting a group of 'cybersluts' attacking patriarchal power in a virtual world.

Faith Wilding, Recombinants, 1992-96, Source: faithwilding.refugia.net

Linda Dement, Cyberflesh Girlmonster, 1995, Source: v2.nl

Parallel to VNS Matrix, Sadie Plant from the UK was exploring how technology could influence feminist theory. She first used the term cyberfeminism in 1991 to describe a new approach to feminism that leverages the internet and digital technology. She elaborated on her vision of cyberfeminism as an approach to understanding the internet as a fundamentally feminine space. She argued that both women and the internet are non-linear, self-replicating systems naturally suited to making connections. Her influential book "Zeros and Ones" further explored these ideas and paid homage to historical figures like Ada Lovelace, highlighting the overlooked contributions of women in technology.

Building on the foundations laid by pioneers like VNS Matrix and Sadie Plant, cyberfeminism gained momentum throughout the 1990s. It attracted a diverse group of artists and theorists from around the globe, including regions such as North America, Australia, Germany, and the UK. Australian artist Linda Dement utilized computer games as a medium to construct alternative female identities, challenging conventional perceptions of gender roles. In the United States, Lynn Hershman Leeson was developing her alter ego, Roberta Breitmore, and by using hired actors and fabricated documents, she brought Breitmore's character to life. Another significant figure in the US was Faith Wilding, who initiated her "Recombinants" collage series which featured amalgamations of machine, plant, human, and animal imagery, exploring the interconnectedness of these various life forms with technology.

Old Boys Network, First Cyberfeminist International, 1998, Source: monoskop.org

Old Boys Network, 100 Anti-Theses of Cyberfeminism, 1997, Source: monoskop.org

One of the most important moments in cyberfeminism’s history came in 1997 with the “First Cyberfeminist International”, organized by the Berlin-based collective Old Boys Network. The collective’s five women, including Susanne Ackers, Julianne Pierce, Valentina Djordjevic, Ellen Nonnenmacher and Cornelia Sollfrank, brought together 38 women from 12 different countries at Documenta X in Kassel, Germany. The gathering was notable not only for its global scale but also for the creation of a provocative anti-manifesto titled "100 Anti-Theses of Cyberfeminism". By the end of the decade, several critical issues within cyberfeminism began to surface. Despite its growing influence, the movement struggled with a lack of a clear definition, presenting various and sometimes conflicting ideas about its core principles and objectives. The early optimism that the internet would serve as a universally liberated space was viewed as overly idealistic. Additionally, there was growing criticism that cyberfeminist writings predominantly catered to an educated, white, upper-middle-class, English-speaking, culturally sophisticated audience, thereby excluding a significant portion of potential global contributors and beneficiaries.

Cornelia Sollfrank, Female Extension, 1997, Source: medienkunstnetz.de

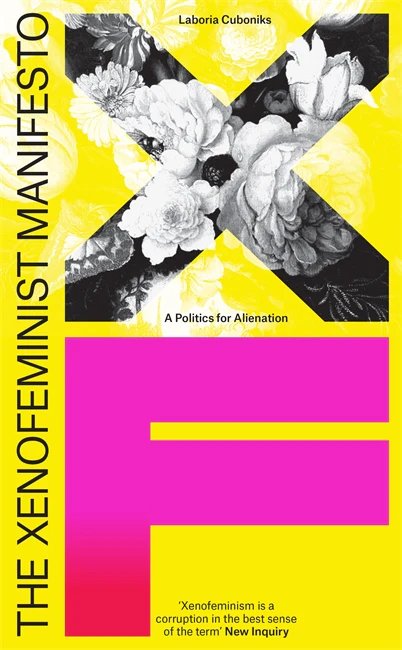

This criticism highlights the perception that cyberfeminism might have lost momentum as a movement or indicated a need for a slightly different approach. In response, the 2000s saw the emergence of Technofeminism, which is often viewed as an extension or evolution of cyberfeminism, but with a broader scope. Technofeminism integrates insights from science and technology studies (STS) and feminist theory to critically examine the gendered aspects of technology, extending beyond the digital or cyber realms. It explores how gender and technology are mutually shaping each other and promotes feminist approaches to technology development, policy, and usage. The aim is to uncover and address gender biases in the design, development, and implementation of technology across various societal aspects. Judy Wajcman, a pivotal figure in this field, provides an analyses in her 2004 book “TechnoFeminism”, discussing how technology and society are interdependent, with examples from the history of feminist movements related to reproductive technologies and automation to illustrate her points.